Like Hamlet or Faust or Frankenstein’s monster, the tragic figure of Don Quixote represents something eternal and essential in the human spirit. Cervantes’ knight-errant seems always to have existed as a cultural blueprint, a means of comprehending the world. It’s a testament to the flexibility and fecundity of Cervantes’ genius that the universe he depicts is discovered anew with each successive generation of readers.

Anne Ludlum, who, along with director David Quicksall, adapted Book-It’s Don Quixote (through Sunday, Oct. 16, at the Center House Theatre; 206-216-0833 or www.book-it.org), opts to see in the tale the “secret ingredient” of Fear Factor or America’s Next Top Model. Yes, it’s true: “There’s self-awareness on the part of the characters in the second part of the book,” Ludlum writes in her program notes, “so they’re almost like people in today’s reality TV. . . . Cervantes created these characters that the people of his world reacted to in much the same way people in our time react to celebrities or fictional characters like Harry Potter.” Such tilting at satellite dishes is symptomatic of Book-It’s often quixotic mission to reinvigorate classic literature for the digital age; sometimes their efforts to modernize a particular text show a peculiar lack of faith, and their bids for relevance can be klutzy. Fortunately, there is less Harry Potter than Charlie Chaplin in the company’s man from La Mancha.

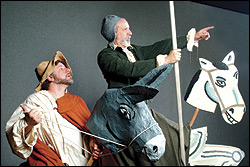

Obviously talented writers, Quicksall and Ludlum locate Quixote’s adventures somewhere between the picaresque and the pastoral, with a strong element of physical comedy that registers just shy of slapstick. In the lead, the lanky Gene Freedman evinces a nice blend of loose-limbed goofiness and deep melancholy, portraying Quixote as a delusional Tramp martyred by a cynical and calculating world. Walter James Baker, who looks like a young Buddy Hackett, plays Quixote’s trusting sidekick, Sancho Panza, as a sort of frenetic enabler; his high-energy antics remove all sadness or plaint from Panza’s character, substituting straight pratfall and upbeat jabber. This comic pairing allows Quicksall and Ludlum to organize the narrative as a series of episodes in a sprawling, buddy road adventure. There’s a lot of action and movement, as well as some wonderfully choreographed fight scenes reminiscent of the reeling balletic brawls in old oaters. The physicality is nicely offset by the use of Cervantes himself (played by Wesley Rice), who oversees, comments upon, and even occasionally inserts his presence into the action. The conceit gives the proceedings a daydreamy feel, and prevents the action from overtaking the story’s more subtle aspects. Windmills and whimsy find a nice balance.

Several other aspects of this production are noteworthy. The small supporting cast is strong, with all of the actors being asked to play multiple roles. The set, designed by Northwest painter Fay Jones, is wonderfully woodsy and rustic looking, with backdrops of Quixote and Panza painted by Jones herself (her husband, Robert C. Jones, built Rocinante, Quixote’s horse). The music, composed by Nathan Wade, is fantastically evocative and blends perfectly with Quicksall and Ludlum’s vision.

The play’s two acts split, roughly, books one and two as originally published, opening with the onset of Quixote’s madness and closing with his death. That’s a big, big book and, obviously, there’s a lot left out. Such a sweep gives the production the feel of being a primer—Cervante’s greatest hits. It might have been more effective to focus on two or three adventures, the better to depict Quixote in all his deep and tragic and comic humanity. As it stands, this is a small, pleasant piece of theater, solidly—if safely—put together.