When Seattle Art Museum benefactors Jon and Mary Shirley recently walked into their house after a long trip, they were struck by the absence of Calders, which are all currently installed at SAM. “It felt 10 degrees colder,” Jon told me.

The Shirleys’ temporary loss is your gain. “Alexander Calder: A Balancing Act,” which shows off the half-century’s worth of choice Calders the Shirleys own, is a rare chance to get a sense of the sweep of an important artist whom Seattleites encounter most often through the monumental Eagle (1971), centerpiece of the Olympic Sculpture Park (and also courtesy of the Shirleys). Eagle is majestic, yet full of such childlike joy that you feel sure Calder would have been delighted a couple of years ago when Greg Lundgren and friends smuggled in a nested baby eaglet and placed the spot-on mini-replica in its shadow.

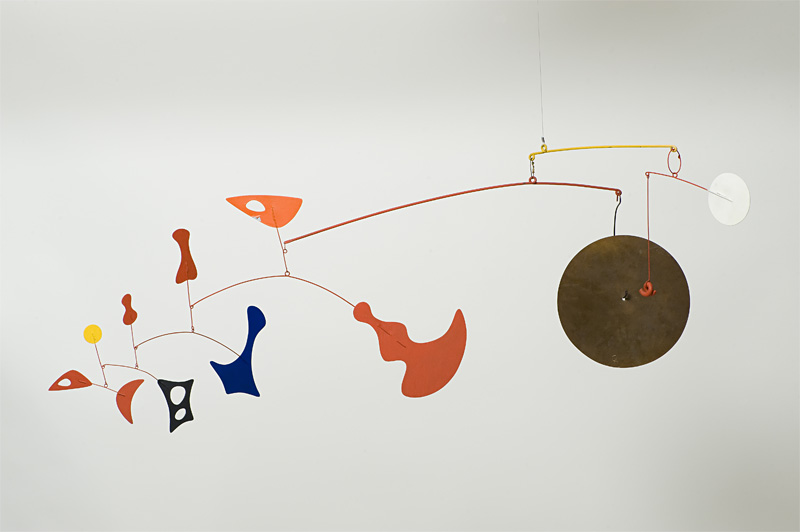

Calder’s public sculptures reveal his heart and mind in works of inventive engineering. But you can’t get the spontaneity of the artist in mid-creation from a powder-sprayed foundry work, however great. That’s what you do see in “Balancing Act,” where large-scale elegiac mobiles like 1965’s Toile d’Araignée (or “Spider Web”) are placed alongside tiny pieces like 1973’s Two White Dots, which you could hold in your palm. The subtle care taken in bending a piece of metal this way or that, the intimate brush of primary color, the idiosyncratic cut shapes, the myriad solutions of balance and cantilevering are wonderfully manifest in these studio works. (Dispersed Objects With Brass Gong, from 1948, is shown above.)

Red Curly Tail (from 1970) almost reaches the ceiling, but it resembles the nearby Two White Dots, with a similar reinforced bar form at the center balance point. In these smaller works, you see Calder coming to necessary structural solutions—a weight at the center of the piece’s lengthy extended arms that works mechanically and visually. These models offer the magic authenticity of the artist’s hand, a record of Calder as he works instinctively.

Other small works show Calder’s ability to make the sparest choice full of sophisticated delight. Crinkly Crocodile (1971) is simply zigzag-bent metal crimped and painted to look like a smiling sinuous reptile. The man had an inner child that would not be contained.

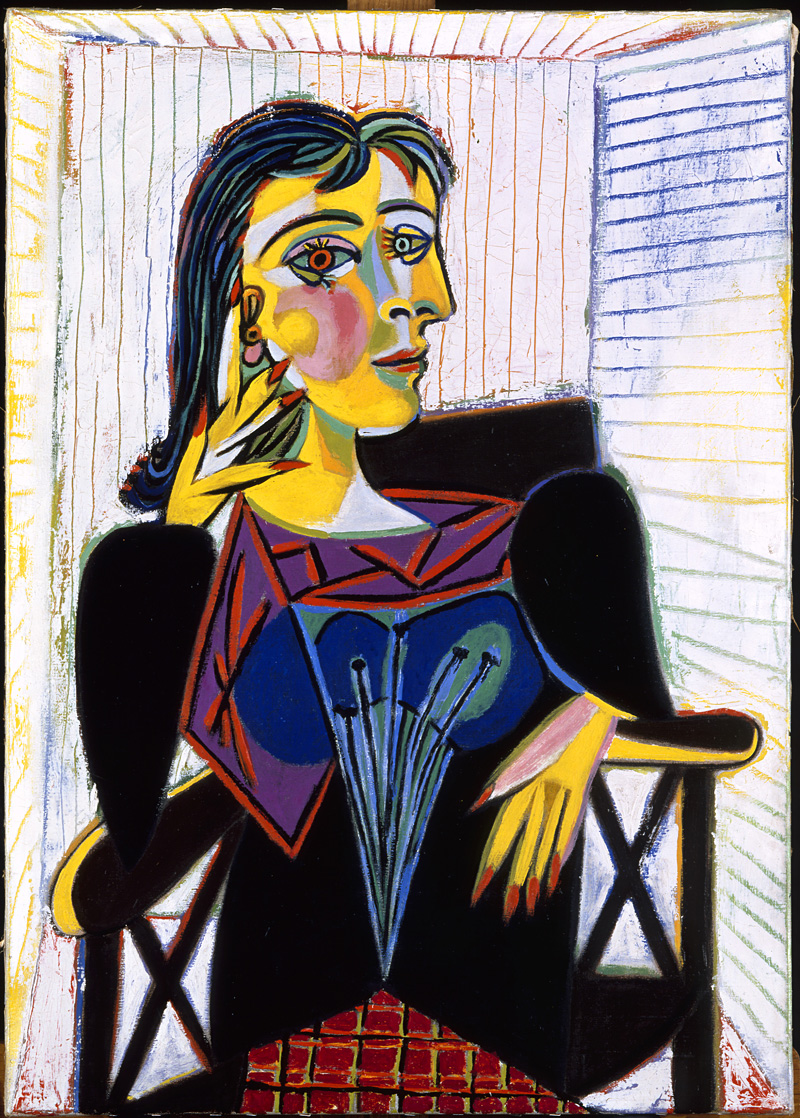

Yet his aesthetic results in works of eloquent complexity. The standing mobile Bougainvillier (1947), a black sheet-metal base supporting vinelike wires with white sheet-metal leaves, is a masterpiece of lyrical authority, with each hanging link, some resembling paper chains, thoughtfully considered. It repays its debt to Mondrian, Picasso, Miro, Arp, et al. a hundredfold in a style Calder’s own. The metal blossoms grow; the metal leaves seem to fall and drift in frail, floating variation, mirrored by shifting shadows on the wall. (Beautifully installed, the show gives Calder’s shadows the space they need to play.) It’s a choreographed metamorphosis whose co-choreographer is nature itself.

Juxtaposing the Calder exhibit with a show of Michelangelo drawings might seem to make for strange bedfellows. But the combo turns out to be a winning one, because the latter show also sheds light on the artist’s more intimate moments. And like Calder, Michelangelo is obsessed with the expressive power of form in motion, his subject the realistic portrayal of the male nude.

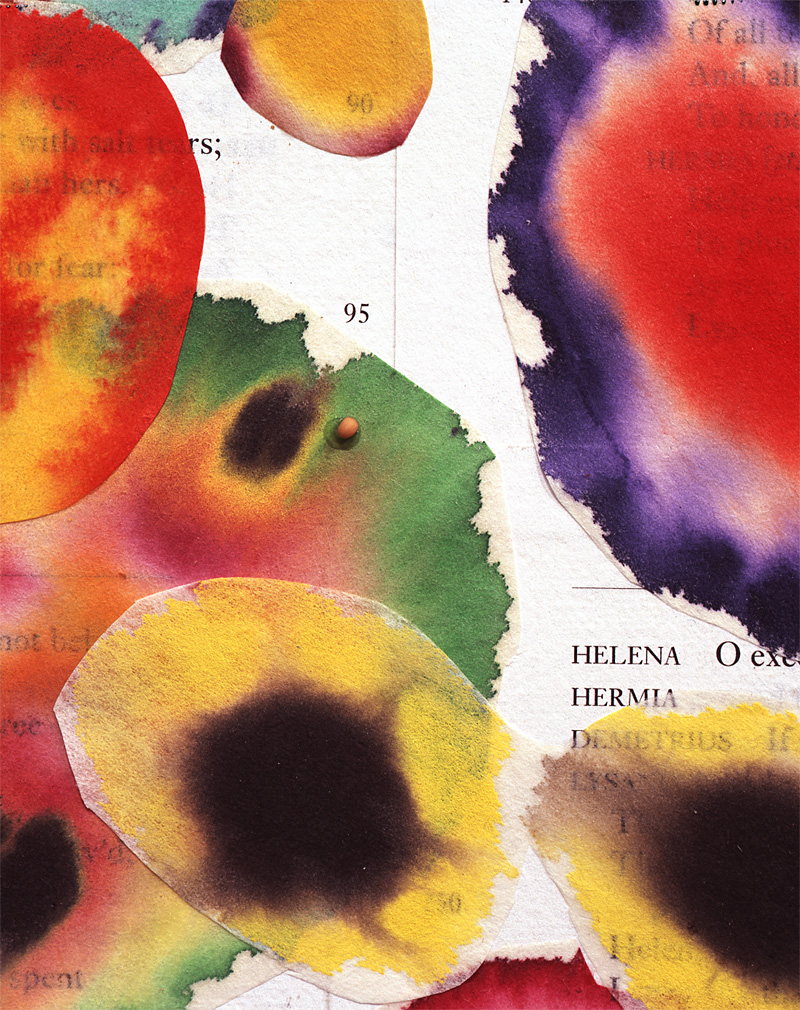

Whereas Calder looked to the world of nature and the universe as a guide, Michelangelo sought mastery as an expression of divinity. He wouldn’t use a figure in a final painting until he’d drawn several studies to elicit perfectly the emotion sought. But the master didn’t want to leave a record of his hard work in achieving mastery, so he destroyed his sketches. There are only 12 Michelangelo drawings in the United States. Twelve others from Italy are in this touring show. Unless you’ve got European travel planned, this is your only chance to see some of the greatest drawings of the Renaissance, not 67 feet up on the Sistine Chapel ceiling but five inches from your nose.

In the 1509–10 Study for Adam in the ‘Expulsion From Eden’ on the Sistine Ceiling, he superimposes drafted lines to get the tension right in the arm closest to God; in the finished painting, Adam’s arm is more extended, more defensive. Michelangelo would hate for you to get this privileged glimpse into his search for certainty. But these 500-year-old drawings, acute with sensitivity and focus, trace the weight of muscle under the skin, the light in the arch of motion. They attest to a man evidently unable to make an imperfect mark.