Why is this show not at EMP? My first thought upon entering the Henry’s visiting exhibition was that if Paul Allen’s 12-year-old vanity museum is to be taken seriously, it’s got to book serious shows. And the paradox is this: While The Record: Contemporary Art and Vinyl is not what I would call serious by the Henry’s standards, it’s exactly the kind of accessible, summery, and even tourist-friendly collection that might engage the masses over at Seattle Center, after they climb down from their Duck tours and before they hop aboard the monorail. It’s got music. It’s got videos. It’s got colorful album covers—some real, some fanciful—that don’t require a Ph.D. to enjoy. There are even listening stations with headphones and turntables. It’s not deep, but it’s fun—unlike SAM’s recent “The Listening Room,” Theaster Gates’ ill-thought-out history project.

Still, Christian Marclay dominates “The Record” so much that it almost feels like his name should be on the marquee. With his epic, 24-hour movie compendium The Clock presently the most-discussed artwork in New York, you’d almost rather see a one-man show featuring more of his work. (Here, he’s one of nearly 40 artists displaying some 100 works from the mid-’60s onward.) Upon entering, in the first gallery on your right, a giant red phonograph arm bobs and skips over the grooves on a record. It’s a video, called Looking for Love, and you could sit there for its entire 32-minute duration—if there was a bench—to pick out the tuneful fragments. The constant interruption prevents you or the music from ever settling into a groove. And yet your ear demands a pattern, some kind of continuity, just as the eye is forever seeking to make order of the world. It’s both frustrating and hypnotic.

Push farther into the show, which originated at Duke University’s Nasher Museum, and there’s Marclay’s 1985 performance video Ghost (I Don’t Live Today). In it, he reprises Hendrix’s Are You Experienced with a turntable strapped to his chest. He’s “playing” it like a guitar, in one sense, but he’s also exploring the temporal aspect of recorded music. As with every chronological increment of The Clock (in which each cinematic snippet shows the advancing time), recorded music is a twofold replication of time—and that’s true throughout “The Record.”

First, all recorded music is old the second it’s done being taped or digitized or inscribed on wax cylinders. Preservation locks the music in time, and every musician’s pet peeve is to be asked to play a hit just as it sounded on the record. Recording is an inherent form of nostalgia, and “The Record” is a very nostalgic celebration of vinyl and turntables. (CDs barely figure, there’s not a cassette in sight, and forget about mp3s.) For baby boomers, the meeting of vinyl and needle is still a sacred ritual.

Second, there’s the duration of a song or album itself—the progression of the needle from the record’s edge toward the spindle, the spooling/unspooling of the tape, the movement of the laser over the CD. (How mp3 bytes are processed, I have no idea.) It’s always the same unit, the same sequence, the same fixed length. The span of a pop single is like a cigarette, a way of measuring and consecrating time.

A record’s visual interest is much more straightforward. Album covers once represented a high form of commercial art—they were a sales aid back when music was actually displayed for sale, not browse-and-clicked. But instead of presenting iconic covers by famous designers (e.g., Warhol’s banana for the Velvet Underground), curator Trevor Schoonmaker mostly goes outside the industry. A welcome example is the personal mythology illustrated by Washington, D.C., outsider artist Mingering Mike, who imagined a pop-star career for himself during the 1960s and ’70s with handmade sleeves, liner notes, and cardboard discs with grooves drawn in ink. There’s something sad, silly, and noble about them—and they’re utterly silent.

Also handmade is David Byrne’s Polaroid-tiled band portrait for Talking Heads’ 1978 More Songs About Buildings and Food. Like the work of Mingering Mike, it has a tactile, pre-digital quality. You can see the overlapping edges of the square photos which, when arranged into a mosaic, render the musicians with an oddly perspectived, larger-than-life quality. There are traces of Warhol and Pop Art (appropriate, since the band formed at RISD), which are more plainly stated in two paintings from Ed Ruscha’s Hit Record series. Independent of what music’s on it, a record’s round, bull’s-eye form—so like Jasper Johns’ target paintings—is a hit. There’s a visual perfection to the vinyl platter; for a half-century and more, the record album simply was the icon of music. Today we can’t say whether music is circular, square, or represented by 0’s and 1’s; it’s just another file on your laptop.

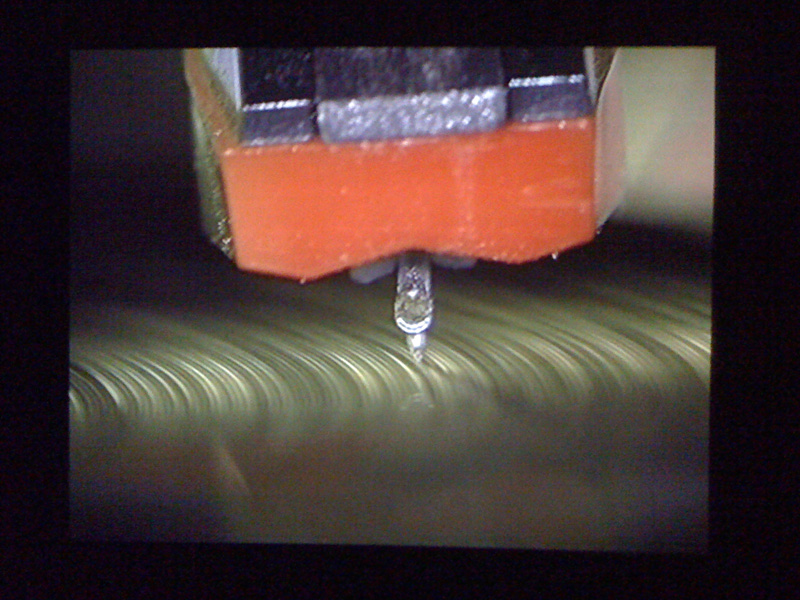

If EMP ever did get around to hosting a similar exhibit, it should give Taiyo Kimura his own workshop and residency. Here, in his comical, whimsical sketches and video Haunted by You, he plays an LP with a chicken leg, buries a portable stereo while it’s running, and slices an apple on a moving turntable using a knife taped to his face. Tourists would love it, and so did I.