Rock critic Greil Marcus coined the phrase “the old, weird America” as a rejoinder to poet Kenneth Rexroth, who said the songs of Carl Sandburg captured “the old free America.” Marcus thought it was stupid to think America used to be free, but isn’t anymore. He also thought the old American folk songs that inspired Bob Dylan’s 1967 Basement Tapes were weird. So Marcus called his 1997 Basement Tapes book The Old, Weird America.

Dylan’s rediscovery of old, weird Americana defied the cliché of his day: psychedelia. In its weaker moments, “The Old, Weird America,” a touring show currently at the Frye, does the opposite—pandering to the popularity of clichéd identity politics. At its best, though, the show dives deep into folk tradition and relates it to the present with a jolt of originality.

Some of the work here preaches to the converted with thumping, didactic self-congratulation. Kara Walker’s silhouettes of Br’er Rabbit lynching a slave are breathtakingly effective, but Sam Durant’s installation Pilgrims and Indians, Planting and Reaping, Learning and Teaching (2006) is tired and obvious. Durant appropriates two kitschy Thanksgiving dioramas from Massachusetts’ late Plymouth National Wax Museum: In one, an Indian shows settlers how to plant corn; in the other, “true” version, Myles Standish bludgeons the First American leader (prior to slaughtering the Pequots and giving God thanks). This is a vivid illustration, but a one-liner whose impact evaporates instantly.

Not so the deeper, large-scale ink and watercolors of Brad Kahlhamer, a First American raised by European-Americans whose work is informed by his days as art director for Topps Chewing Gum. Fields of nervous, scribbled skulls wind into Northwest coast motifs in Mad magazine style and illustrations of a barely clad white girl holding a rifle. More than preachy agitprop, Kahlhamer’s visions are emotional, complex, and memorable. So are Barnaby Furnas’ watercolors and paintings of Civil War scenes splattered with visceral violence, sci-fi peculiarity, and video-game action—a time trip into an uncanny, unforgettable present.

Eric Beltz’s disciplined graphite portraits of the Founding Fathers are what a smart, snotty, and extravagantly talented high-school kid might scrawl in a Pee-Chee, riffing off iconography from American currency. Jefferson tells posterity, “Good Luck Assholes.” Washington has chopped a “Fuck You Tree.” Stars whirl round the presidents’ heads as if they’re stoned. Yes, the rendering is masterful, but the message is too sophomoric to last for the ages.

Compare the minimalist cool of David Rathman’s ink drawings of macho cowboy figures, each captioned with similar comic-book sass: “Hell you ain’t dead, just shut up a little.” Beltz is technically brilliant, but Rathman expresses more, going beyond satire to reveal the tough guys’ pathos and vulnerability.

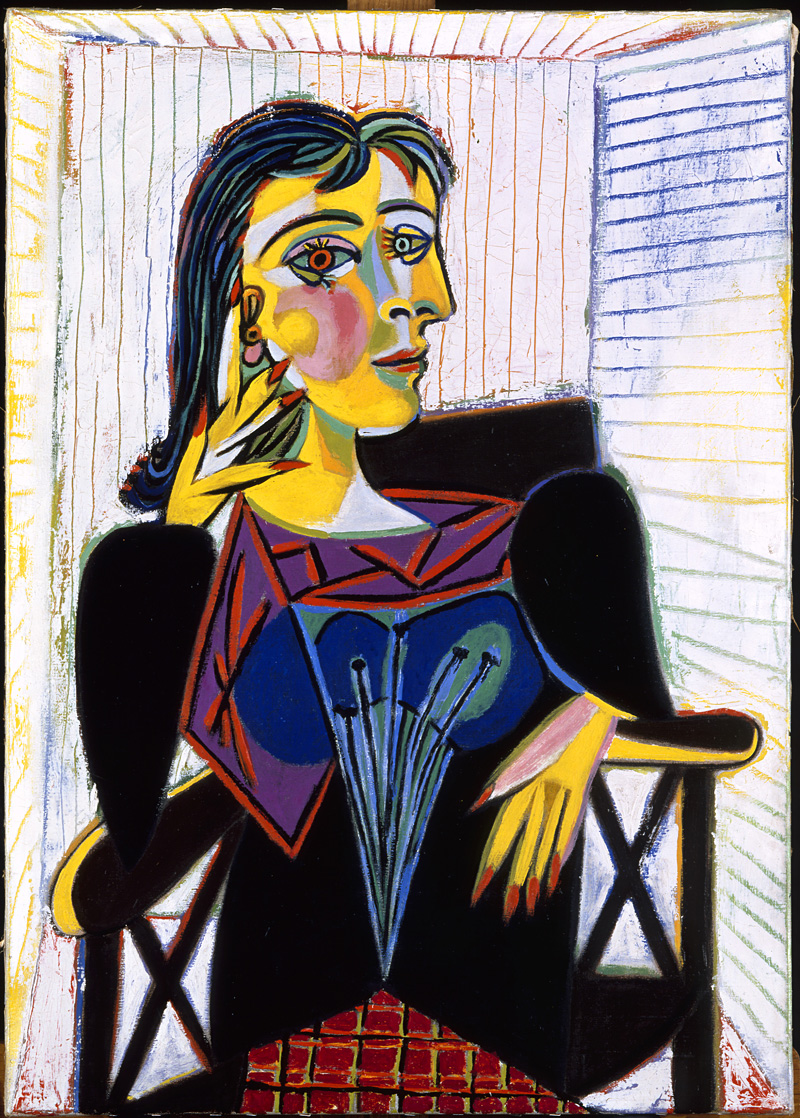

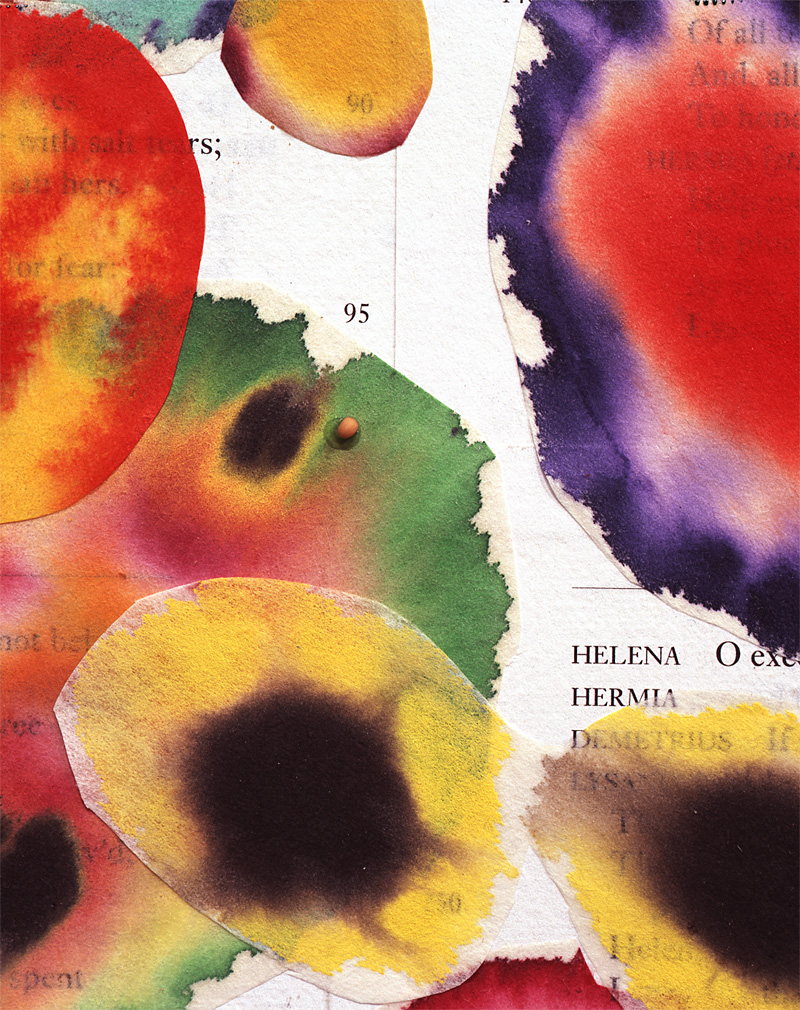

The show’s most striking work nails universal truths that continue to nag at the American conscience. Jeremy Blake’s video Winchester (2002) takes on the guilt and paranoia of a society preoccupied with violence. Old photos of San Jose, Calif.’s Winchester Mansion—owned by a mad heiress who believed she could only ward off the ghosts of those killed by Winchester rifles by forever rebuilding—are transformed into frightening drips. The sound of a grinding, old-timey film projector gives way to a music box playing “The Stars and Stripes Forever,” while phantom shadows of a frontiersman take aim at a female in a darkening window. The window becomes a bullet hole; it bleeds into a brilliantly painted Rorschach, like an hallucinatory Morris Louis abstraction heightened with internal anxiety. The Rorschach becomes white phantasmagoric spots, then wallpaper haunted by ghostly faces, which double into images of dead animals at the feet of riflemen. On and on the stunning imagery loops, forcing us into Mrs. Winchester’s unbalanced mind—akin to that of so many Americans who compulsively build fortresses that only feed their fear.

Cynthia Norton’s 2004 Dancing Squared also produces shivers. At first it seems a benign, if odd, construction: four red-and-white dance frocks hung symmetrically on a stark aluminum frame. Abruptly, the whole thing spins wildly like a berserk carny ride, the frilly skirts like whirling dervishes whose movement puts them in a trance. It’s out-of-control, headless, mechanistic mindlessness, suggesting exuberance induced by outside forces, group-think fanaticism incited by propaganda, drugs, misdirected anger, and desire. The visual metaphor of compulsive propulsion calls to mind a whole procession of all-American fanatics; it’s as if, somewhere deep in American culture, there is a scary force, a faceless phantom square-dance caller who calls the shots—and the gunshots.