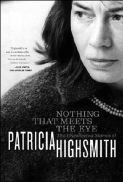

NOTHING THAT MEETS THE EYE

by Patricia Highsmith (W. W. Norton & Company, $27.95)

I’VE NEVER BEEN one who “loves a good mystery.” Then again, Patricia Highsmith didn’t write mysteries—she wrote mysteriously.

Highsmith, a New York native, lesbian, and expatriate who died at age 74 in Switzerland in 1995, shaped her stories and novels around the arch of murder, tragedy, and intrigue, but she did so with such odd warmth and psychological intuition that they always transcended the limitations of typical whodunit fiction. Highsmith’s oblique, loosely tied, confounding character studies asked why, or how, instead of who.

Highsmith’s stories gained new popularity with the movie The Talented Mr. Ripley, which was based on a novel (the first in a series of Ripley novels) about a cunning and charming con man. Although Ripley was not the first of her stories to be developed into a screenplay (Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train is taken from her first novel), the movie’s popularity introduced her name to the everyday vernacular of contemporary readers and writers. The stories collected in the latest volume of Highsmith’s work, Nothing That Meets the Eye, are published here for the first time, and although the potential for disappointment with posthumously culled material is high (there must have been a reason this work wasn’t published while the writer was alive, right?), the stories in this volume all but prove an oft-expressed theory that Highsmith was her own harshest critic, that she kept much of her best work to herself.

Separated here into Early Stories (1938-1949) and Middle and Later Stories (1952-1982), her relatively short, evanescent tales seem to arrive out of nowhere before they disappear again into the fog they create. Her early fiction in particular, as noted in the afterword by German literary critic Paul Ingendaay, has an experimental mode, one that captures the ill ease and ruin of a crime or wrongdoing but does not wrap the ending up with an overly clever twist, a pat resolution, or an easy answer. The writer gave great weight to editing and would whittle away at her stories until only the most essential words remained on the page. As a result, Highsmith’s language is economical but highly illustrative, much in the way that her characters are plain but given to thoughts of the macabre. Highsmith had a profound understanding of the human psyche, and even this previously unpublished work bares that truth.

THE BOOK’S FIRST story, “The Mightiest Mornings,” concerns the path taken by a runaway New Yorker. The unsatisfied city-dwelling cab driver disembarks from a train with seemingly random abandon. As he steps off the landing and begins to wander the streets of his new hometown, we realize that he isn’t even certain which state he’s in; he is simply content to be somewhere “other.” When he befriends a small girl, the otherwise amiable townspeople begin to narrow their gaze on him, and again he feels like an outsider, like he doesn’t belong.

One of Highsmith’s favorite characters—she creates this one over and over again—is that doe-eyed, enigmatic little girl who quietly occupies corners while carefully pushing the plot along. This character re-emerges throughout the collection as well as in Highsmith’s previously published work. In “Mornings,” Aaron never commits any misdemeanors, nor does his small friend, Freya, although the pair does briefly visit a strange house in the forest that the girl claims is haunted by the legacy of a murder. The story’s tension lies not in some horrible, inhuman act but in the odd friendship, the quick and creepy peripherals, and Aaron’s failure to make good on his fresh start—it is suspenseful while also an incisive examination of 20th- century life. Place it next to Anton Chekhov’s narrative ruminations about average people.

Like the ubiquitous young child, the theme of disappointment, the not-quite-realized life, is omnipresent in Highsmith’s work. Like Chekhov and Raymond Carver, she often moves very quickly through the story’s most dramatic curves, leaving plenty of room to simply and eloquently examine the ordinary. As often as these lives intersect with some sort of realization, event, or catalyst, they just simply are. They are unsatisfied, they are unsure of their place, and they are paralyzed inside their processes and routines. Reading about them is as ironically fascinating as it is unsettling: Identification leads to dismay. If I am like them, you begin to think, my life must be just as gray.

Though Highsmith once torched over 300 pages of her work in a fit of self- editing, over 30 of her published titles circulate today, and Nothing That Meets the Eye captures the essence of that work—her emotional expertise—excellently.