Understandably, many young artists turn to their own training (or mis-training) as a subject. Contemporary art often takes itself as a subject, much for the same reason that writers write campus novels about writers or filmmakers seem drawn to Hollywood lampoons. But what if an artist’s background is far removed from the academy? What if manual labor, not figure drawing, defines him? In his first solo museum show, 32-year-old Chilean artist Rodrigo Valenzuela reflects indirectly on his early struggling years as an undocumented immigrant in Canada and the U.S. His was not the easy, direct path to art school, as he explained during the opening of Future Ruins late last month at the Frye.

“All my 20s, I was doing construction,” says Valenzuela, a slim, friendly figure who greeted the press wearing a natty gray suit. “I cleaned offices in Montreal,” where he first settled in part because he spoke French but not English. Without proper work or immigration papers, he bounced from Boston to Olympia, where he did landscaping and moving work while studying philosophy at Evergreen State College. “I did pretty much every job,” he recalls of those lean years before moving to Seattle in 2006—just in time to witness the Great Recession. (Here also he earned an MFA at the UW.)

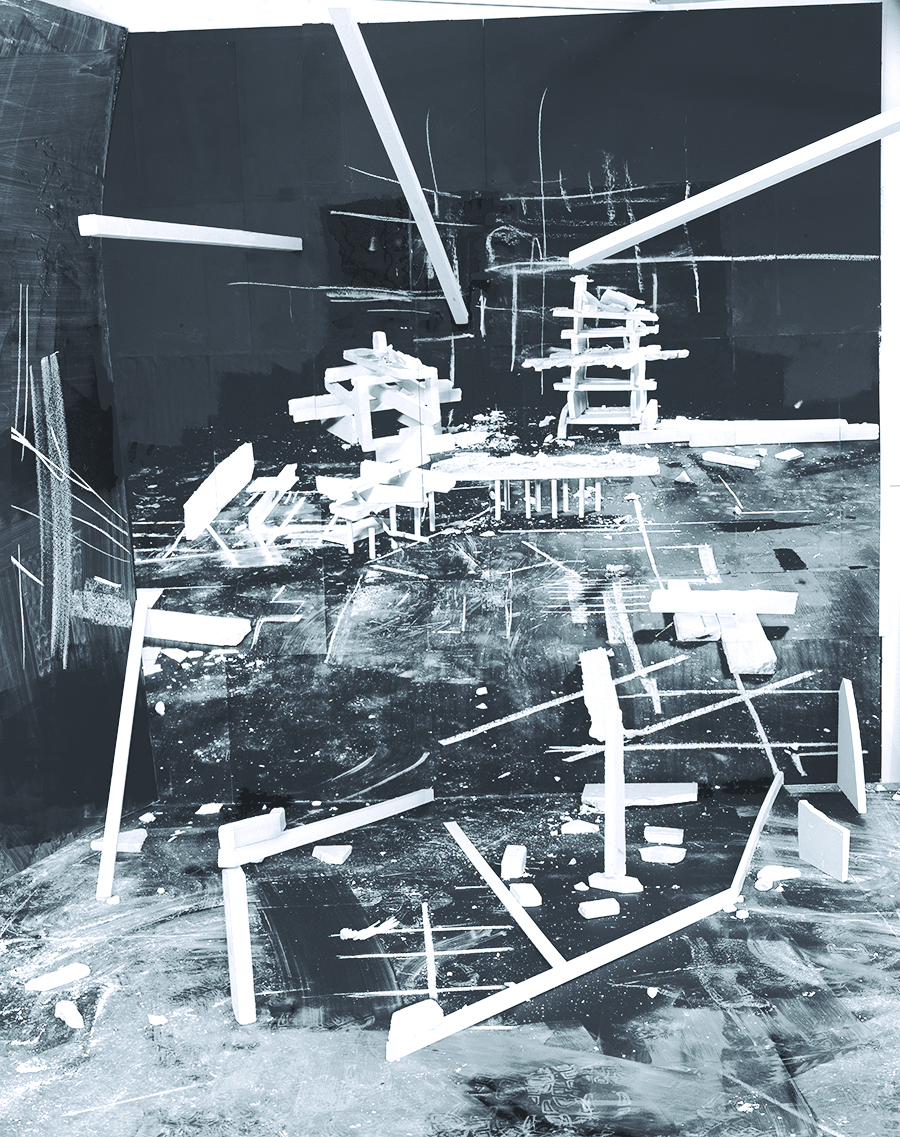

The past couple of years have been boom times in Seattle, but in three videos and a room-filling installation of construction scaffolding and photos (called Hedonic Reversal ), Valenzuela wants to direct our attention to what he calls “the aesthetic of ruins without the social or economic failures that accompany them.” Unlike downward-spiraling Detroit, in other words, ruins are a kind of anomalous luxury to us prosperous Seattleites—something unusual to be scrutinized and oddly savored. “I walk around the city all the time,” says Valenzuela, looking for signs of decay and new development (the latter surely outpacing the former these days). He calls it “searching for sadness in order to feel a little more human” and compares it to watching an old Hollywood tearjerker.

Frye director Jo-Anne Birnie Danzker more explicitly compares his show to the old English notion of the folly—a new-built ruin of the Romantic era that was meant to sentimentally contrast the bustling present and the idyllic past. In early 19th-century England, steam power was poised to remake the economy. Ersatz ancient castles, fallen into rubble, seemed the more poignant for their irrelevance. Today in Seattle, Valenzuela sees a weird dissonance between the construction workers who erect new Amazon buildings in South Lake Union (and the janitorial crews who clean them at night) versus the legion of fresh-scrubbed young office workers, key cards dangling from their belts, who write all that invisible, precious code. “They’re not making anything tangible,” says Valenzuela tartly.

As for those unseen—or willfully ignored—folk who actually make things, or remove them, with their hands, Valenzuela has collectively dubbed them The 13th Man. An example of their labor is seen in the new three-screen video El Sisifo, which depicts workers cleaning up the football stadium at Rice College in Houston (where Valenzuela is a visiting instructor). Their Sisyphean labor never ends, since there’s always a new game, a new season ahead. Two prior videos, Maria TV and Diamond Box, draw from interviews Valenzuela conducted among maids and day laborers here in Seattle (he paid them $15 an hour for their time, he explains).

The Marias—not their real names—of Maria TV represent a distilled and abstracted account of life on the margins. Valenzuela’s intent in the video is to foreground those generic maids, always named Maria, you see hovering around the edges of a glamorous telenovela, to give these overlooked women a voice. In conventional media, at least, “There is no room for working-class women,” he says. Here, in heightened, rewritten form, he’s eliciting that familiar melancholy ache—again, think of the folly—and crossing it with a bit of TV melodrama. What he’s teasing out is that “something about your everyday life that is beautiful and mysterious,” no matter what drudgery that everyday life might entail.

The men of Diamond Box meanwhile speak more directly of their hardships crossing the border, performing menial work, and avoiding la migra. Their experiences are concrete—like Valenzuela’s own past work history. In those interviews, he says, “I’m looking for me,” albeit at an earlier stage in life. (Though none of these day laborers are likely to become artists.)

Collectively, his show intends “the construction of a counter-narrative for and about the working class,” says Valenzuela. His videos are fairly direct in that regard, while Hedonic Reversal is more of a challenge for the viewer. The scaffolding and painter’s tape suggest construction, of course, and 17 rather similar black-and-white photos depict a process of building or collapse. (Whether the intention is toward order or disorder isn’t clear.) The impression is of a dusty construction site hastily abandoned, a project stalled—possibly for years or decades. If there’s a piquant sadness to his workers, Valenzuela’s photos convey a sense of gnawing incompletion (again: Sisyphus). There’s no pleasure in a job that never ends, in a mess never cleared away, yet we stop and stare at the rubble. And why? Says Valenzuela, “We have this aesthetic of ruins within us.”

bmiller@seattleweekly.com

FRYE ART GALLERY 704 Terry Ave., 622-9250, fryemuseum.org. Free. 11 a.m.–5 p.m. Tues.–Sun., 11 a.m.–7 p.m. Thurs. Ends April 26. Valenzuela gives a talk at 2 p.m. Sun., March 1.