ON FRIDAY THE 13TH, Seattle will get a snappy new neighborhood cinema, and the Scandinavian capital of western America will be able to say that it has had an active movie house at 2044 Market Street in each of the last 10 decades.

In 1997, Ballard’s Bay Theater closed after 82 years of more-or-less continuous operation as a small local movie house. It had laid claim to being the oldest operating film venue on the West Coast, although there was little remaining visual evidence of this historic distinction. Originally named the Majestic, remodelings and deferred maintenance had eroded any majesty it may have had, and what met the eye was a nondescript bargain venue with uncomfortable seats and peeling paint that was just limping along.

At the same time it had nicely filled a geographic and economic niche—how many communities still have working movie houses, and low-priced ones at that?—and warmed the hearts of those who rooted for a one-screen mom-and-pop operation in an industry dominated by huge chains and their suburban sixteen-plexes. Here was a true urban theater, built to the sidewalk on Ballard’s main drag, a human-scaled independent business in the midst of others of its kind.

After closing, it was bought by Ken Alhadeff, scion of a family well regarded for its community philanthropy and experienced in mass entertainment. (Its most prominent venture was the old Longacres racetrack.) Alhadeff loves movies and grew up watching them in his own neighborhood theater, the now-vanished American in Seward Park. At first he weighed restoring or remodeling the Bay, but that quickly proved impractical. It was a wood-framed building whose bathrooms and lobby were lilliputian, whose walls and roof were rotting, and whose tiny site was further squeezed by two side alleys.

The sensible course was to tear it down and build afresh, a decision that also reflected Ballard’s steady transformation from a place regarded as isolated, stodgy, frugal, and geriatric to one that was drawing a younger, hipper population. No more lutefisk jokes and “yaaah, sure, you-betcha” wisecracks for this suddenly hot part of town. Stand outside the Bay today, and you’ll see four latte joints within 50 yards.

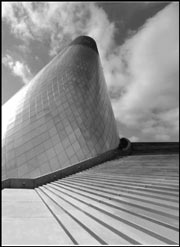

Alhadeff’s son Aaron says that Ken wanted to “revitalize a community” and “uplift Ballard.” Having opted for a new building, Alhadeff set out to do it right. He hired high-style modernist Belltown architect Ed Weinstein, whose industrial-chic Banner Building and North Police Precinct H.Q. have won design awards, and asked him to fit three screens into a space that formerly held just one. A triplex would allow him to negotiate for desirable new releases as well as giving customers an expanded choice. The exhibition plan is to mix first-run titles, classics, and family films.

BUT THREE SCREENS meant that Weinstein was presented with formidable challenges in the areas of space-planning, access, and servicing. The 50-foot by 95-foot site wasn’t really big enough for a good-sized auditorium and lobby, yet he had to fit three of them, each isolated acoustically from the others and containing its own separate ventilation system and projection room, plus three stairs and an elevator, into a ninth of an acre.

The architect managed to do it, but not without some compromises. The main lobby is a bit small, the main stairs are narrower and steeper than one would wish, and the narrow corridor to one of the smaller third-floor auditoriums might be mistaken for a service passage or fire exit. It was an accomplishment that Weinstein likens to “putting 10 pounds in a five-pound bag.”

But enough about space planning—what about the architecture and interior design? Here, the five-pound bag is a mixed one. There are some clear triumphs, such as a large window in the upper lobby that provides a broad southward vista for patrons and a glimpse into the house for pedestrians and drivers. What a rarity for a theater, yet what an obviously good idea. Making it even better are large, spare, and elegant red neon-outlined letters in that window that spell out B-A-Y in a Roman face.

The detailing of the entrance is also exceptional: The ticket booth and its flanking walls and doors are made of Honduran mahogany accented with brass inlaid trim bands, and the doors also contain large brass porthole windows, all of it a metaphor for Ballard’s ongoing maritime industry and dubbed by the theater’s manager Brent Siewert “a Chris-Craft motif.”

This wood-and-brass composition looks as much like an interior treatment as it does an exterior one, but, unfathomably, it stops at the front door. Inside, things are more mundane and inconsistent. The major portion of the building front is taken up by the grand upper window, the triple-decker marquee, and a brick-and-stone perimeter element. The brickwork and its limestone medallions and trim bands, says Weinstein, are a symmetrical and abstractly classical gesture meant to be a good neighbor to the nearby Ballard historical district without mimicking it literally. The intention is good, but the result is a bit bland and uneventful—it would have been more interesting to see Weinstein treat this building frontage less symmetrically (after all, the lobby behind it is not symmetrical), in the modern, slightly edgy, metal-clad manner that he employs so well.

The marquee, designed by the National Sign Company, is not convincingly proportioned (it’s neither vertical nor horizontal), in part because it’s triple-decked to accommodate the three-space, three-film plan. It displays the words MAJESTIC and BAY in a clunky, hard-to-read cutout typeface that was custom designed for the job. Usually, a marquee adds great visual flair to a theater, but less so here.

Finally, we have the interiors. Weinstein designed the basic volumes and layouts of the three auditoria in tandem with a theater consultant, and they are pleasant and workable. The main house of roughly 300 seats has a very steep slope in the last seven of its 13 rows, and this creates a striking visual form as well as enabling good sight lines.

Other than this, the interiors are problematic. They were designed by Marleen Alhadeff, Ken’s wife, and tend to diminish the impact of the architect’s efforts. High quality materials abound, including Russian Volga blue marble and more of the mahogany used in wainscoting and ceiling coves, but they don’t always add up to a consistent design expression and often seem domestic in impulse rather than reflecting the nature of a place of public assembly. Many of the poster frames in the lobbies are gilded, baroque, and fussy, while others are simple black-lacquered items. The Alhadeffs have shown great concern for individual details—from major ones such as the Dolby Digital EX sound system to more mundane ones such as providing two-ply toilet paper in the rest rooms—but architectural details need to be part of a coherent visual framework. The decor often fights with the rest of the building design, and sometimes even with itself, as when a squiggly patterned carpet meets a zigzag perimeter of large quarry tile in each lobby. The walls of the theaters are not architectural surfaces but rather draperies of blue velvet. Could this be a film buff’s homage to David Lynch?

IN A WAY, this internal contradiction parallels a basic conflict within Ballard itself—the district is part historic city and part in-town suburb. Some of it is solid, compact, pedestrian-scaled, and urbanistically rich, while other sections are banal, automobile oriented, land-consuming, and unfriendly to people afoot. Much of the recent construction, such as the supermarket and drugstore a few blocks east of the Bay, has embodied the values of suburbia. Fortunately, whatever its interior lapses, the Bay Theater enhances Ballard’s urban character, and that’s even better than real-butter popcorn and bargain matinees seven days a week.