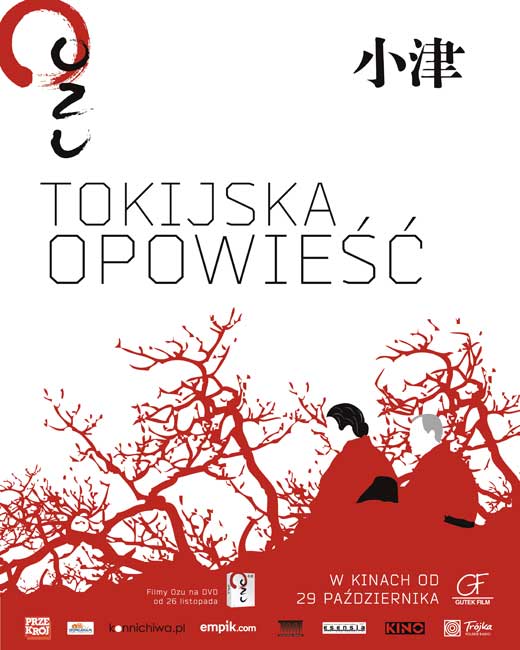

Yasujirô Ozu’s great and mournful 1953 Tokyo Story considers the passing of a generation. An older (but not elderly) mother and father travel from their distant rural home to Tokyo. There they visit one married son (a doctor) and a married daughter (a beauty-shop proprietor). The widow of another son, Noriko (wonderful Setsuko Hara, Ozu’s favorite actress), also helps look after the couple during their stay. Their grandkids have no interest in the visitors, and their grown children are too busy to be good hosts. (Their idea of a favor is to send their parents to a noisy, rowdy spa—anything to get the old folks out of their hair.) “I’m surprised how children change,” marvels the father. “We should consider ourselves lucky,” his wife replies. Amid Japan’s fast-rebuilding postwar economy, at least their ungrateful offspring have jobs, spouses, and roofs overhead. Neither visitor is surprised by their kids’ busy indifference. In Ozu’s world, this is the price for seeing one’s children get ahead: being left behind. Yet not all among the harried younger generation are so hard-hearted toward their elders. The youngest daughter lashes out at her siblings, then confesses to Noriko, “Isn’t life disappointing?” The response is sad, not bitter: “Yes, it is.” She, like her in-laws, is content with what basic human decency can be summoned—or salvaged—out of the relentless new urban order. Ozu periodically frames smokestacks and electrical wires looming overhead: This is progress, he says, and no amount of pining can turn it back. (NR) BRIAN MILLER

Sept. 21-26, 7:30 p.m.; Sat., Sept. 22, 5 p.m.; Sun., Sept. 23, 5 p.m., 2012