MAKING MY WAY through Roy McMakin’s new exhibit at the Henry, I experienced a flash of recognition at the banal object before me: a white, five-panel door with no knob.

As someone who has recently discovered the tiny victories and profanity-inspiring defeats of home remodeling, I have an intimate knowledge of McMakin’s piece. I see it every day. It has taunted me as I’ve tried to hang it in the entrance to the bathroom of my tiny 1920s-era house. I pass it every morning on the way to brushing my teeth. I am more familiar with it and its textures than perhaps any other 7-foot-by-2-foot piece of wood.

Or so I thought. McMakin’s door turned out, on closer inspection, to be much more than a door. Well, not much more: It was a cabinet, too, concealing a chest of drawers behind it.

Such jokey hybrids are at the center of McMakin’s art. What appears to be a refrigerator turns out to a dresser, with table legs jutting out from its backside. Overstuffed chairs are set on swivels.

Since founding the Domestic Furniture Company in Los Angeles in 1987, McMakin, now a Seattle resident, has been fiddling with furniture, architecture, paint, and design. Puns?both literal and figurative?abound in this collection of 20 years’ work (and in the show’s groan-inducing title, “A Door Meant as Adornment”).

Furniture and mass-produced design are entrenched in our consciousness to the point of being invisible. We become intimate with the objects in our homes; eventually we don’t even see them: the curve of the couch backrest, the plastic chairs collecting rain on the porch, the turned wood knobs on our dressers. Much of the Henry’s exhaustive retrospective of McMakin’s work links commonplace objects to notions of memory, home, and loss. You come away with freshness of vision.

ON ENTERING THE exhibit, you encounter a grandiose piece of turned wood?a recent work titled Marian Maroo’s Porch, which pays homage to the female lead in the 1957 musical The Music Man. Meant to replicate an imagined fragment of an imagined home, this piece provides a sort of stage-set entrance to a world of memory through furniture.

Next we’re confronted with a wool carpet imprinted with text from Dickens’ Hard Times?a discussion between two characters about the value of art versus the much more practical domains of math and science. Says one: “You don’t walk upon flowers in fact; you cannot be allowed to walk upon flowers in carpets.” On hesitant feet I wonder, “Should I step around the piece or walk across? When does a home furnishing become something to stare at and write essays about and not use?”

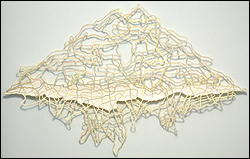

McMakin has created a set of objects specifically for the Henry’s art-deco rotunda: four cylindrical pieces that perfectly fit into the gallery’s semicircular niches and a table assembled from the cut ends of two-by-fours. Again, these lamps, stools, and other hybrids ask us to re- examine notions of the decorative and the functional. Do you sit on it? Do you look at it? How do you regulate your bodies differently in a gallery than at home?

For me, the most powerful piece here is Lequita Faye Malvin, a jumble of 19 fragments of furniture tucked inside an enclosure of sorts and all painted a uniform gray. It seems I’ve seen that dressing table before, that clock face. All of these fragments are meant to evoke the artist’s memories of a grandmother’s bedroom, furniture as Proust’s madeleine.

Other installations document McMakin’s eclectic approach to design and architecture. A grand architectural model of a lavish L.A. home is set upon a gorgeous stained-wood table, its carved elevations elegantly morphing into the table surface. A photograph records an emblematic McMakin interior design: a doorway placed freestanding within a room?a barrier as well as an entryway, a piece of carved wood, a sculpture. Much of McMakin’s art reverses form and function: What was once useful is reset in a new context so that its impracticality becomes the very thing that makes it interesting to look at.

The rear gallery features an IKEA-esque display of various and sundry McMakin furniture designs piled on high shelves. Some of the surprises here are baroque in their theatrics: A banal plastic deck chair is cast in bronze. However, most of the jokes are more subtle: dressers with oversized, impractical knobs; found end tables arranged in a Mondrian-like assemblage; a simple table that reveals the luscious nature of polished wood. On the wall, a tapestry makes yet another reference to The Music Man. I began to seriously wonder if McMakin feels a bit like Harold Hill, conning unsuspecting art patrons into paying good money to look at the furniture they can easily find in the living rooms of River City.

“Roy McMakin: A Door Meant as Adornment” continues at the Henry Art Gallery through Sun., May 9.