Tucked behind a small parking lot off Dexter Avenue next door to a crumbling Hostess cake factory, sits a small gallery. In this part of the city, where commuter traffic zips past, the gallery doesn’t get much walk-up traffic. And that’s probably for the best, since it’s only open for an afternoon each Thursday.

But the little-publicized Wright Exhibition Space is home to one of the 20th century’s most important collections of art. And it’s the one public venue for the massive holdings of Virginia and Bagley Wright, Seattle’s most influential and legendary arts patrons.

It’s not hard to see the contributions the Wrights have made to the city’s arts landscape. Seattle Art Museum was transformed from a provincial, primarily Asian art venue into an institution with an impressive collection of contemporary art—in large part because of the Wright’s donations over the past 40 years. Browse the museum’s selection of modern art and you’re likely to see a Wright donation or promised gift: Willem de Kooning’s 1943 Woman, Robert Rauschenberg’s 1963 collage painting Manuscript, and works ranging from the Northwest’s Mark Tobey to Cindy Sherman’s staged photographs. The museum’s signature sculpture, Jonathan Borofsky’s Hammering Man was acquired with funds from the Wright’s art fund. (The Wrights were also the original investors in Seattle Weekly.)

But for all the works on public display at SAM and Western Washington University (where the Wrights helped fund collections of Northwest art and modernist sculpture) there are hundreds of other works that get only an occasional public showing.

Virginia Wright, speaking from the Wright Exhibition Space, indicated the couple privately owns nearly 300 works of art, many of which are on display in their North Seattle home and their gallery on Dexter. What makes the total collection so extraordinary is the depth of its aesthetic variety. Virginia Wright is characteristically modest about how the couple amassed one of the country’s most diverse collections: “I did follow what I thought was happening in the art world, but what we really knew was who to listen to.”

Two of the century’s most important critics—Clement Greenberg, who championed Jackson Pollock and abstract expressionism, and Richard Bellamy, who made the case for Warhol, Lichtenstein, and Pop Art—were early and influential confidants of the Wrights and helped build the collection.

Virginia Wright was born into the wealthy Bloedel family, which had made its fortune in the timber industry. After studying art history at Barnard College in New York City, Wright stumbled into a job assisting Sidney Janis, the Manhattan gallery owner who would solidify Pollock’s reputation. “What I learned from Janis was a real curiosity about what comes next,” she said. “He saw new art as a dialogue in answer to the art of the past.”

This interest in the next big thing served the Wrights very well as collectors. The Wrights were essentially the Warren Buffetts of the art world—finding under-priced investments ahead of new trends.

In the early 1950s, they were buying Pollocks, Rothkos, and other abstract expressionists for mere hundreds of dollars. In the 1960s they began collecting Pop Art by Lichtenstein and Warhol. In the 1970s, they were ahead of the curve on minimalists like Carl André, Donald Judd, and Ellsworth Kelly. In the 1980s, they shifted focus to an array of artists in a variety of styles: Germans Anselm Kiefer and Gerhard Richter and Americans John Baldessari, Jim Dine, Cindy Sherman, and Jeff Koons.

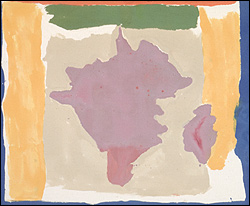

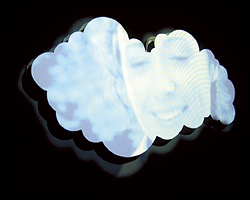

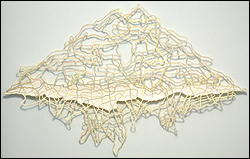

They didn’t always follow the advice they sought. “We listened to Clement Greenberg—for a while,” Virginia Wright told me. A diehard proponent of abstraction, Greenberg refused to accept Warhol and Pop Art as legitimate art. He talked the Wrights into buying the works of color field painters such as Morris Louis, Helen Frankenthaler, and Jules Olitski—successful abstract painters in their own right. But many of these color field works—now on display in the current show at the Wright Space—fell from critical notice almost entirely after the 1960s. The current show, curated by Virginia Wright, might revive the reputation of these artists, whose primary concern was the sheer pleasures of color and light.

The Wrights don’t have many regrets about pieces they wished they’d bought. “But we do have regrets about what we sold,” Virginia Wright admitted. The couple got rid of works by Warhol, Philip Guston, Louise Nevelson, and Ed Ruscha, among others. “But we’d often sell to buy other art, so we didn’t feel too badly about it.”

Much of the Wright’s legacy is destined for SAM and other public institutions. The Wrights wouldn’t offer specifics, but when asked if some of SAM’s new downtown expansion was designed to house the Wright’s art, Virginia Wright said coyly, “Oh, I hope so.”

SAM’s magnificent Olympic Sculpture Park, which will begin to take shape next year near the city’s waterfront, will benefit immensely from the Wrights. Packing up and moving from the couple’s 7-acre property in North Seattle will be Tony Smith’s 1967 minimalist piece Wandering Rocks, Mark di Suvero’s massive steel and cut-log sculpture Bunyonchess, (his first commissioned work, from 1965), and Anthony Caro’s steel balancing act, Riviera completed in 1974.

The Wrights still occasionally buy a piece of art. Jules Olitski’s Thigh Smoke, which is now on display in the color field show, didn’t make the opening bid of $20,000 at a Sotheby’s auction in 1997, and the Wrights quickly snatched it up. The couple recently bought a painting and photos from Eric Fischl’s important work, “The Krefeld Project” in 2003.

Virginia Wright readily acknowledges that they aren’t on the cutting edge anymore. They’ve never been particularly interested in conceptual or video art, for instance. “I think it’s partly generational,” she said. “People tend to be engaged in the art and culture of their own generation.” Wright indicated that she and her husband (who are now in their 70s and 80s, respectively) will continue to slow the pace of their acquisitions and enjoy what they have. “Besides,” she said, “I’m running out of space.”

“Color Field and Related Abstractions” at the Wright Exhibition Space, 407 Dexter Ave. N., 206-264-8200. 10 a.m.–2 p.m. Thurs. Runs through Jan. 28.