FRIDAY 2/24

Film: Poisoned Apples

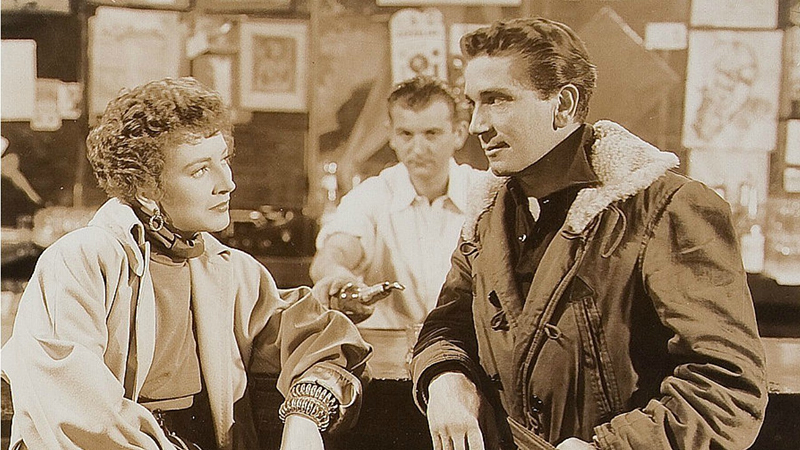

Opening his weeklong Noir City film/lecture series is one of Eddie Muller‘s personal favorites: the 1949 Thieves’ Highway, directed by Jules Dassin. Says Muller, “It’s set in downtown San Francisco, my hometown; takes place entirely in the dead of night; and suggests that life will always be a struggle against the worst aspects of human nature.” Those aspects are embodied primarily by corrupt produce broker Lee J. Cobb, but the farmers and truckers seeking to get their wares to market are also tainted by the system. Thieves’ Highway presents a microcosm of ruthless postwar capitalism. A young war veteran (Richard Conte) can hardly find a decent job (sound familiar?), so he drives 400 sleepless miles to San Fran with a load of apples to sell. He needs the windfall to marry his tepid girlfriend, and also to avenge his father—who was cheated and crippled by Cobb’s character. Everyone’s looking for an angle, a cut of the precious cargo above or below what Conte furiously decries as “Four bits a box!” Much as he hates being hustled or swindled, he becomes part of the vile racket. Shot mostly on location in the Embarcadero, Thieves’ Highway provides a star turn for Dassin’s Italian girlfriend, Valentina Cortese, as a hooker who mocks her would-be rescuer with winsome sarcasm: “Go ahead, lover! Tell me what a bad girl I am! I’m lost unless you save me!” All 14 titles in the series are being screened as double features; following at 9:30 p.m. in The House on Telegraph Hill, Cortese plays a Holocaust-haunted woman who steals another’s identity to reach San Francisco. There, as you’d expect, more troubles await. SIFF Cinema at the Uptown, 511 Queen Anne Ave. N., 324-9996, siff.net. $7–$12 (individual), $35–$60 (series). 7 p.m. BRIAN MILLER

Stage: The Crimson Howl

“Look at these pictures,” says painter Mark Rothko in the Tony-winning Red, “Look at them! You see the dark rectangle, like a doorway, an aperture, yes, but it’s also a gaping mouth letting out a silent howl of something feral and foul and primal and real.” In John Logan‘s engrossing play, we spend 90 minutes with the now-iconic abstract expressionist as he emits an extended, not-so-silent howl about art, integrity, and other weighty concerns while preparing an enormous commission for the Four Seasons restaurant in the late 1950s. His only company onstage is a young assistant named Ken (a fictional character), who refuses to blend quietly into Rothko’s routine. Director Richard E.T. White found apt actors to help him reveal what he calls a “wonderful sensuality about the textures of the play, the choosing of the colors, the ingredients that go into making something as simple as the three-letter word: red.” Longtime Seattle favorite Denis Arndt, a commanding performer, takes on Rothko. (I still cherish his masterful turn years ago as George, another kind of prideful yet despairing man, in Intiman’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?.) Conor Toms, whose dewy demeanor belies a core of strength (recall his Homer in Book-It’s adaptation of The Cider House Rules), should be an appropriate foil as Ken. (Previews begin tonight; opens Feb. 29; runs through March 18.) Seattle Repertory Theatre, 155 Mercer St. (Seattle Center), 443-2222, seattlerep.org. $12–$49. 7:30 p.m. STEVE WIECKING

Film: Strangeness on a Train

World War II was looming and nigh inevitable when Alfred Hitchcock directed The Lady Vanishes (1938). Beginning on a London-bound train from the nation of “Mandrika,” the story starts small, as a young debutante (Margaret Lockwood) notices when a chatty fellow passenger (May Whitty) goes missing. Little old Miss Froy, as she’s called, is the MacGuffin in the movie: Searching for her mere person, with the debonair assistance of Michael Redgrave, leads to the discovery of a much larger, Europe-threatening web of espionage and secret codes. On the train and in their snowbound inn, the travelers form a constellation of types: plucky Brits against Teutonic villains (enter Herr Doktor Egon Hartz!), surrounded by various Continental clowns. The mood is light, no matter how many storm clouds are gathering. Soon before leaving for Hollywood, Hitchcock has here perfected his comedy-thriller style—one that also neatly resolves into a marriage plot. Even so, history was outpacing the train: In another year, screen villains could simply be called Nazis, and there was no need for Mandrika when Germany was the avowed enemy. (Through Thurs.) Grand Illusion, 1403 N.E. 50th St., 523-3935, grandillusioncinema.org. $5–$8. 7 & 9 p.m. BRIAN MILLER

SATURDAY 2/25

Opera: Keep It Simple, Stupid

If you were an opera fan around the middle of the 18th century, you probably would have been a partisan of one of the prevailing styles. Italian opera was all about vocal display; no one much cared what you were singing about. The unvarying aria forms that were ideal vehicles for showing off were also Procrustean beds on which attempts at narrative were stretched into irrelevance. French opera offered lots of dance and lavish instrumental color, but could also be stilted and stuffy. In reaction, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, a composer as well as a philosopher, wrote the ostentatiously uncomplicated The Village Soothsayer, in which simple folk sing simple tunes about simple emotions. (It was a hit—and 250 years later the equation of unsophistication with authenticity is still a pop/rock article of faith.) At last came Christoph Gluck, who in 1762 synthesized all this—melody, spectacle, directness—while prioritizing literary and dramatic quality, choosing for his experiment in reform the oldest musical tale of all, Orpheus and Eurydice. As he wrote later, “I have striven to restrict music to its true office of serving poetry by means of expression and by following the situations of the story, without interrupting the action.” It sounds logical now, but it was controversial, even avant-garde, then. Yet it’s his operas that have survived, not his rivals’. Seattle Opera’s production stars tenor William Burden as the musician who tries to rescue his love (Davinia Rodriguez) from death. And since tragic endings were not yet de rigueur in serious operas (that required yet another operatic reform, decades later), he succeeds. (Through March 10.) McCaw Hall, Seattle Center, 389-7676, seattleopera.org. $25 and up. 7:30 p.m. GAVIN BORCHERT