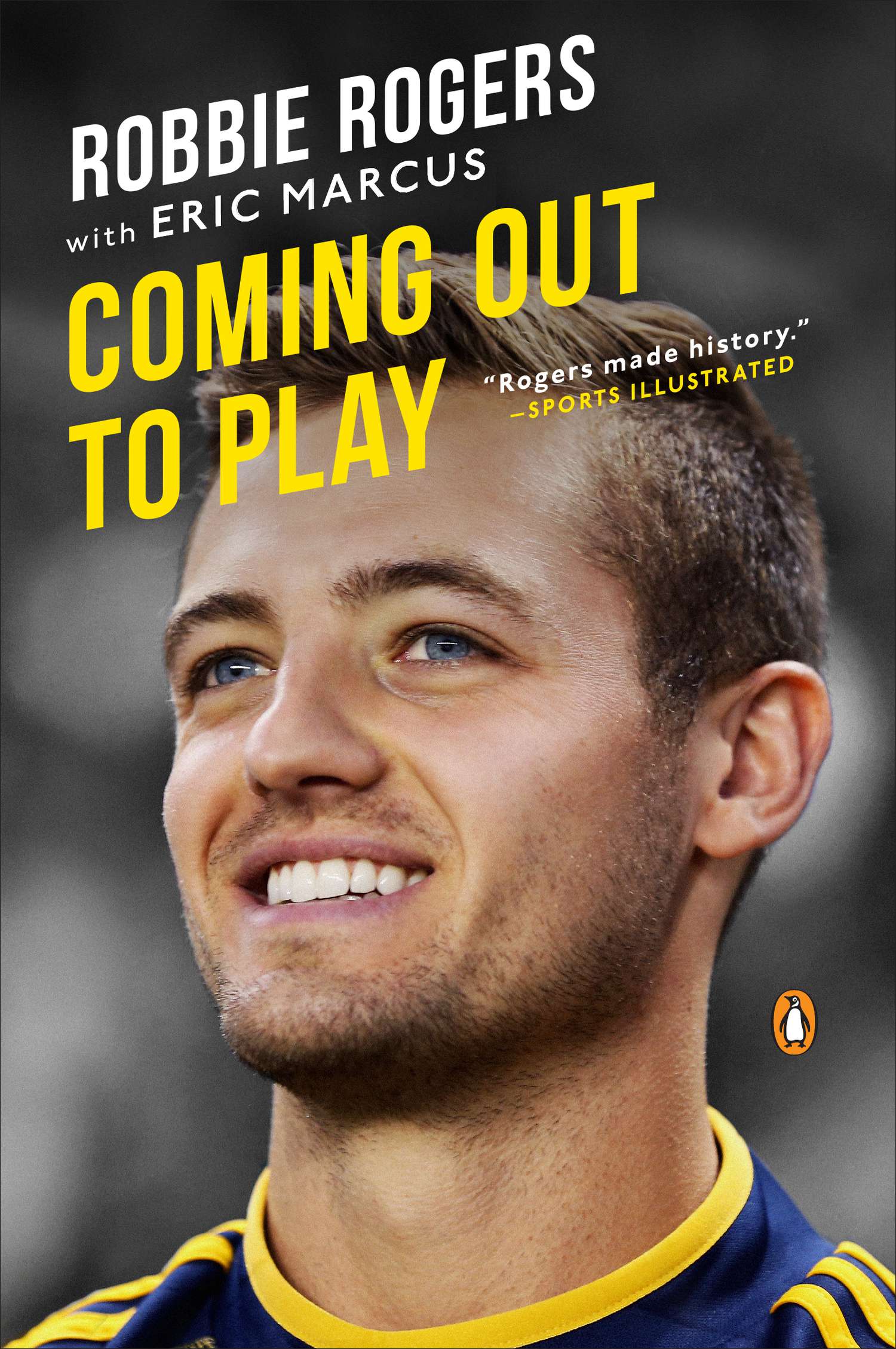

The one disheartening thing about Robbie Rogers’ Coming Out to Play (Penguin, $17), the newest entry in its genre—Memoir League, Gay Conference, Sports Division, men’s team—is how little had changed since its groundbreaking ancestor, The David Kopay Story, from 1977. Kopay, a former running back and co-captain of UW’s 1963 Rose Bowl team, dropped his bombshell a full decade before Rogers was born and 36 years before the midfielder, playing in England at the time, posted a tell-all letter to his blog.

The good news: Rogers, now 27, assumed that retiring from soccer would be inevitable, but the public response was entirely positive, inspiring him to rethink that decision. (Good choice: Now playing for the L.A. Galaxy, he got to share in the glory of winning the 2014 MLS Cup on Sunday.) Yet as he tells it, the details of his life in the sports closet were, even after all those years, all too similar to Kopay’s—and those of diver Greg Louganis (Breaking the Surface, 1995), footballer Esera Tuaolo (Alone in the Trenches, 2006), and basketball’s John Amaechi (Man in the Middle, 2007).

Several themes run prominently through all five books: the sense of isolation, especially within the machismo of sports culture; the unsateable addiction to praise for athletic achievement as a counter to that isolation; the fear of a career-destroying outing (all but Rogers came out after their playing days ended); the casual and omnipresent gay slurs and sexual boasting of the locker room, and the lies they necessitated; the attempts to self-reprogram, using women in the short term physically and in the long term emotionally; and the concomitant difficulty of maintaining a social life of any kind—much less a supportive circle of friends, much much less a relationship—while living the itinerant, cog-in-a-machine life of a pro athlete. (With very few exceptions, none of these four players of team sports ever spent more than two or three years in one city, and even Louganis was constantly preparing for and traveling to competitions.)

The more you read all these books, though, the harder it becomes to clearly distinguish what is a universal experience from what is merely a cliche of the genre. Four of these tomes, for instance, begin identically, in medias res on field, court, or platform, ironically contrasting a public moment of career climax with the anguish of a private secret. (Kopay’s also opens dramatically in its way, with his decision to tell his story to a Washington [D.C.] Star reporter. Its sporting high point comes when he returns to Seattle for the 1976 varsity/alumni game—his first public appearance after that interview. From the stands, surprisingly, “not a single boo.”) Here let’s stipulate, however, that Rogers and Louganis enlisted the same co-writer, Eric Marcus, which may partly explain the formula.

For Rogers, the dramatic impetus is a mid-match concussion during his debut with the team in Leeds, England. (“But as I lay paralyzed on the field . . . all I could think was, Who am I and how did I get here? ”) From there, he goes on to describe his all-American SoCal childhood (chapter 4’s title, “Golden Boy in a Golden Family,” sums it up) and a fairly typical career path for a top-level U.S. male soccer player, bouncing from Europe to MLS and back, interspersed with callups to the men’s national team.

Though his relationship with his parents was generally strong—there’s a reason “soccer mom” has become synonymous with achievement-oriented, time-and-money-sacrificing parenting—they were conservative Republican Catholics, which didn’t smooth Rogers’ path to self-acceptance. (Though he was lucky compared to these other four men, whose fathers ranged from distant to abusive to absent.) Neither did soccer itself, to the likely disappointment of liberal Seattle fans and parents who might hope the sport was above that kind of bullshit.

“Gay” and “fag” were put-downs no less prevalent (if possibly less vicious) in soccer five years ago than they were in football 50 years ago. Sounders fans may be ruefully amused to read that one source of in-his-face homophobia was Rogers’ then-teammate Steven Lenhart, now notorious as one of MLS’s biggest on-field assholes. He’s since come around, reports Rogers, who describes Lenhart as “one of my biggest supporters . . . our friendship has not only survived, but thrived.” For those curious, a few current and former Sounders make cameo appearances in his book: Brad Evans, Kasey Keller, Marc Burch, Marcus Hahnemann, and most heartwarmingly Sigi Schmid, Rogers’ coach in Columbus, who led the team to a 2008 MLS Cup and who texted Rogers during the original flurry of media attention to encourage him not to retire.

In contrast to

Coming Out to Play, as well-scrubbed as Rogers’ own nice-guy persona and consequently almost totally devoid of dirt, these other four books are all dishier. The David Kopay Story was incendiary for its tales of “God-was-I-drunk” encounters with Theta Chi brethren and one Washington Redskins teammate, and especially for its blind-item assertion that three other then-active NFL players were gay. (If not its bolted-shut closet door, what definitely has changed in the NFL? Of his 1973 season with the Green Bay Packers, Kopay boasts, “My salary was up to $32,000”—equivalent to $171K today, when the guaranteed starting minimum is $420K.)

In addition, Kopay, as a pioneer, seems to have felt obligated to produce not just a memoir but an overview of the whole subject of gay men in sports. There’s a bibliographic list of press citations from across the country; an appendix of several supportive letters; and an examination of sports literature (Ball Four, Semi-Tough, North Dallas Forty, The Front Runner) for mentions of the topic. As a result, his book’s prose occasionally goes sort of Kinsey-ish: “What people are really saying, when they say that homosexuals can’t be trusted as coaches or teachers, is that homosexuals are somehow different from heterosexuals in being unable to control their sexual feelings in a professional public situation. My own career helps give the lie to this.”

Though no reader, obviously, would wish Rogers had had a tougher life, his book is Wonder Bread compared to the luridness in Louganis’—particularly his long romantic relationship with a manipulative sociopath—or Tuaolo’s, whose childhood was by turns idyllic (a banana farm on Oahu) and nightmarish (the deaths of several family members, including a beloved brother to AIDS). He perhaps travels the furthest from scarifying traumas to happy ending; his catalyst for coming out was his adoption of children with his now-husband and the impossibility of continuing to pretend that the man who accompanied him and his twins everywhere was not also their parent.

But the most richly readable book of all is Amaechi’s. Gayness, it turns out, is one of the least remarkable aspects of his story. (Man in the Middle is the only one of these five in which coming out and its aftermath plays no part—the book was his coming-out.) A biracial, bookish, overweight, Erasure- and Earl Grey-loving English boy who did not touch a basketball until age 17, Amaechi was six years later starting for the Cleveland Cavaliers. And his sexuality, though he speaks comfortably about it, seems pastel among these more improbable life details. Naming names and settling scores with coaches and management who wronged him, in a comic voice that recalls, say, Stephen Fry with a hint of Christopher Hitchens, his book is more flamboyant than Rogers’ by just the same margin that the NBA is more flamboyant than MLS. He writes, “For the first time, I could see the potential fun in [lacrosse]—even if I never did get my jollies from two hours drenched in sweat and mud, mashed up against miscreants half my bulk.”

Rogers’ style, on the other hand, is straightforward and unadorned. In fact, it reads very much like—well, here, see if this rings a bell:

“I loved Elton John’s music. He’s a great singer-songwriter and his music is something that makes you feel good. I always thought he was gay but that wasn’t an issue for me, and I didn’t see how his being gay could be a problem for anyone, but clearly it was for my mom. That really scared me. It made me think that I could never say anything to to my mother about what I already suspected about myself because she would think there was something wrong with me, too. We listened to the rest of the song in silence.”

This passage—and it’s not at all atypical—is, to my ear, purest Judy Blume. This is not a slam; Blume’s is exactly the readership for whom Coming Out to Play will do the most good. If Rogers does seem to play his cards a bit closer to his chest than these other authors, it makes his story more relatable, more universal; and his career success and boy-band adorableness won’t hurt either.

He admits his intent—“being a role model for that young Robbie Rogers who was just starting out in his sport and wondering whether he could be himself . . . I could be an example of someone whose difference not only didn’t get in the way, but also made his life better.” In an odd way, Rogers’ book is designed to help make its genre obsolete—another shot at the goal of making being an out athlete no big deal.

gborchert@seattleweekly.com

ELLIOTT BAY BOOK COMPANY 521 10th Ave., 624-6600, elliottbaybook.com. Free. 7 p.m. Thurs., Dec. 11.