The Night of the Iguana

ACT Theatre; ends Sun., Aug. 28

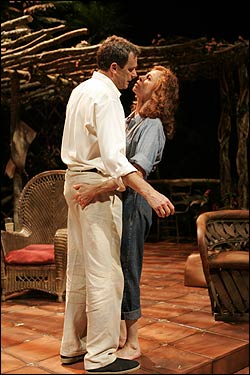

Jon Jory’s production of Tennessee Williams’ sex-and-salvation opus is so unbelievable, it barely exists. The show is blatantly fraudulent and distressingly blah, despite its continued attempts to convince us otherwise with a lot of pacing and yelling and the kind of carnal missed connections better suited to the staging of a bedroom farce than a work by one of America’s two or three greatest playwrights.

Iguana finds a defrocked, detoxifying, and delinquent Southern minister–cum–tour guide holed up at a flea-bitten hotel in Mexico with a few other lonely travelers. There’s a lot of railing at God, but much more of a singularly exposed Williams—entering into the last round of his own game of self-delusion with this 1961 play—praying that our shared, beautiful deceptions be allowed to help us live out our desperate days and inconsolable nights. Or, as Hannah Jelkes, a faded flapper also in need of lodging south of the border, puts it, “The moral is to accept whatever situation you cannot improve.”

You cannot, unfortunately, improve what’s gone wrong in Jory’s staging, which becomes evident within moments of Patricia Hodges’ appearance as Maxine, the widowed, horny proprietor of the rundown villa. Hodges reaches for the earthy, loose-limbed languor of the role, but she doesn’t look right in her jeans. I don’t mean that as a slight on designer Marcia Dixcy Jory’s costume choices; I mean that Hodges doesn’t look right in her jeans. Her imperious Maxine doesn’t seem like a jeans wearer, nor does she have the relaxed sensuality of a woman who’s casually screwing her establishment’s two young Mexican staffers (Ben Gonio and Dennis Mosley, both more happy puppies than the oblivious Latin studs one would suppose ol’ Tennessee had envisioned). Hodges also can’t strike a spark with John Procaccino’s lapsed Rev. Shannon, for which I cannot blame her since Procaccino is even more miscast than she is.

The production is so miscast, in fact, that there’s a loud voice in your head screaming “Liar!” each time a character onstage utters a line that does not fit the description of the performer we’re watching. Procaccino’s Shannon, who arrives at the hotel with a broken-down busload of randy church girls and their bullheaded chaperone (Laura Kenny, all bluster), tells old flame Maxine, “A spook has moved in with me,” yet he doesn’t appear to be haunted at all—twitchingly neurotic and irritated, yes, but nothing resembling a man with an unshakable spiritual crisis. And while I’ve always had a soft spot for Suzanne Bouchard, who shows up as Hannah with her “97-years-young” poet grandfather (Clayton Corzatte, just fine), I’ll confess to stifling a slight cough when she claims to be “pushing 40.” Shannon, who falls for Hannah, much to Maxine’s dismay, eventually calls the virginal spinster a “fantastic cool hustler”; she calls him one right back, and there you are in your head again howling, “Liar! Liar!” And so it goes.

There is no sexual or romantic tension between any of these people. When you’ve got the time to contemplate the wonders of the sound design—good on you, Dominic Cody Kramers, for that crackling storm—something is amiss no matter how proficient the technical work (and you can count Paul Owen’s credible set among the night’s other few successes). Director Jory addresses all the angst in a frantic manner that captures some of Williams’ humor but none of his poetry, making the play feel twice as long because it isn’t grounded in a world where anyone can believably do and say the things on display. When Procaccino drops to his knees and begs Kenny not to break his human pride, it’s so removed from any inner conflict it plays like a hyperbolic joke; Lada Vishtak’s Charlotte, the reverend’s persistent teenaged amour, has been directed as a screeching comic harpy.

Act II has a little tenderness, but it’s a sign of how much Jory has mishandled everything that the production’s loveliest scene ends up as a kind of punch line. Hannah shares with Shannon the story of her one intimate experience, a brief encounter with a lonely, middle-aged businessman who shyly masturbates with an article of her clothing. When Shannon asks Hannah why she wasn’t disgusted, she calmly replies, “Nothing human disgusts me.” It’s a moment of pure grace, and Bouchard catches something of Hannah’s humbled dignity, but the scene goes so awry that the opening-night audience was laughing, which caused a disgruntled older patron next to me to mutter, “It’s not funny.”

No, it’s not. This Iguana never finds its way into a universe where people can be both pitied and admired. “We live on two levels—the real level and the fantastic level,” says Shannon. Yes, we do. The misfits of ACT’s Mexico don’t reside on either plane. STEVE WIECKING

Joe Bean: A Rock Fable

UW Ethnic Cultural Center; ends Sun., Aug. 21

It’s not that Joe completely blows. The Bainbridge Island High School–spawned musical that updates the Book of Jobas a sort of satire of Northwest New Age types is surprisingly tuneful and sung by its dewy 15-member cast with palpable Judy-and-Mickey-have-a-show-in-the-barn brio. Composer Mark Nichols is the string arranger for the Walkabouts, and auteur of lots of popular local shows in cahoots with Joe co-lyricist and coauthor Bob McAllister. This work was invented out of sweaty necessity in two weeks, when Bainbridge High couldn’t acquire rights to Jesus Christ Superstar in time for its 2003 show. And it’s nothing if not ambitious: Andrew Lloyd Webber’s company is called the Really Useful Theatre Company; Joe Bean is published by the Really Big Publishing Company.

The show sasses the Bible with Webberian facetiousness. After the chorus serenades Joe (Mark Power) as “the happiest, luckiest, friendliest, wealthiest, funniest, mellowest, sickeningly modest, stable, religious guy we know,” a terrorist bomb levels Joe’s uninsured mansion, his son dies by friendly fire on the first day of a war, and his daughter dies on prom night. His wife dumps him, and he then gets a skin disease, lives on the street, joins a 12-step group, and is needled by an acupuncturist with abbreviated training. The Devil (Jason Kappus in a pinstriped suit, red tie, and socks) talks God into hazing Joe: “Here’s the plan, Stan, we’ll take this everyman . . . dangle him over the frying pan.” God (Loni Kappus, dressed like Mother Nature) demands to know where Joe was when she created the universe: “Kepler and Einstein, boy/Lifted my beer stein, oy!/Where were you?”

Most of the wordplay is just silly, and it worsens the dramaturgical flaw of the biblical original: the opaque motivations of Joe’s tormentors and the utter arbitrariness of Joe’s situation. The disparate costumes make little sense, the vaguely sketched characters even less, and the choreography is from hunger, though there’s a talented break-dancer who spins on his head (the roles are so hard to identify, I can’t tell which actor is which).

Yet, the melodies often rise to distinction, in tunes like “Got to Get Down,” “Learning Acupuncture,” and some song with a lilting opera-ish aria. (The songs with the heaviest dramatic burdens—Joe’s son’s death, Joe’s climactic cri de coeur—are the weakest.) Power’s voice has some power, though the rest of the cast’s vocal talents are uneven. Kappus’ voice of God is sweet, if rather meek—an effect exacerbated by her microphone, which kept cutting out every other syllable she sang.

And this brings us to the uncanny calamity that befell the opening-night show. The amplification system plagued God’s mike the most but also stole maybe 20 percent of the words right out of the singers’ mouths. The lights flickered on and off all night at random, sometimes plunging the folks onstage into darkness. It happened five times in the first five minutes. This is the worst lighting and sound design I’ve seen in 30 years, and I used to review community theater. Word, Bainbridge people: This show at least deserves to be seen and heard. TIM APPELO

![]() True West

True West

Theatre Unlocked; ends Sat., Aug. 27

Theatre Unlocked’s previous production was a well-rendered take on Wallace Shawn’s brilliant and disconcerting Aunt Dan and Lemon, staged in a tight, sultry space that gave new meaning to the idea of intimate confrontation. Patrons were sitting smack in the middle of the titular Lemon’s living room, a daring move that granted Shawn’s politically charged play just the sort of face-to-face confinement it deserves.

This time around, they’ve upped the ante, setting Sam Shepard’s drama of brotherly love and hate in a semiunfinished residential basement shot through with four-by-four studs and a jiggered sound system that has the audio wafting in through a pair of plastic draped windows. At one point during the show, when some keys flung into the audience disappeared under the risers, a patron simply tossed her own set of keys to the actors—that’s how close things are. It’s a nice change from the projected-voice distance that typically separates patrons from the performers, and here it works to imbue the action of two brothers at a psychological impasse with an aura of sweaty threat and hair-trigger spontaneity.

The play opens onto a scene of tense, renegade domesticity, as Austin (Josh Lanza), a Hollywood screenwriter, pecks away at a manual typewriter while his grizzled brother Lee (Matthew Byron Cassi) paces the room, swilling cheap beer. The brothers’ relationship is defined by a complicated tangle of resentments and an overweening sense that each possesses what the other requires: Austin, spiritually compromised by his profession, longs for his brother’s outlaw life of desert solitude and take-what-you-need criminality; Lee, who feels he has some stories of his own to tell, desires the success, flouncy women, and, most of all, easy money of a movie writer. Both have committed the perilous error of romanticizing the other’s life in an individual search for authenticity and some semblance of personal integrity, all of it under the shadow of a drunken absentee father who himself has disappeared into the desert badlands. All hell breaks loose when the fast-talking, strong-arming Lee convinces Austin’s producer, Saul (Erynn Rose), to option his idea for a “true” Western in lieu of Austin’s screenplay.

As the embattled brothers, Lanza and Cassi are excellent, each bringing a particular flair to Shepard’s rough-and-tumble image of modern masculinity. Lanza’s Austin is an uptight nebbish, a man yearning for “something real” beyond the false friends and empty gestures of the Hollywood shuffle. Cassi, he of the gruff voice and mountain-man beard, is perfect as the family’s overbearing black sheep, given to stealing televisions and conning everyone in sight.

The only problem with this engaging and moving show has to do, ironically, with the setting. At times, the actors appear unable to modulate their performances to the tight confines of the makeshift stage; the result is that a yell or a kicked beer can becomes an overwhelming gesture that reverberates out of proportion to the action at hand.

But this is otherwise an excellent production, slowly and surely drawing you inside its modern-day vision of Cain and Abel and a dangerous game of desert solitaire. RICHARD MORIN