The computer game industry is a bit like the early days of opera: Composers are exploring untested ways of combining music, story, and visual spectacle.

Just as the first opera composers, in the late 1500s, could look to medieval mystery plays and liturgical dramas for some hints on how to make this new genre work, many game composers have experience in film and TV music to draw on. But the interactive aspect of games demands a new approach. Film and TV are linear, whereas games are all about multiple possibilities: Events can be repeated or omitted or unfold in an unpredictable order. The new challenge to composers is adapting music to this open structure, making the course of the music dependent on game play.

Seattle’s a major center for game development, and some local composers are relishing the chance to pioneer a medium. Many of them met last week in a symposium organized by the Seattle Composers Alliance and the National Academy of Recording Arts & Sciences (i.e., the Grammy people).

Some game music uses a layering method, like Marty O’Donnell’s score for the gun-battle-in-space game Halo. If you haven’t played one lately, you might think that game music equals Pac-Man-esque beep-boop jingles. But O’Donnell’s score, recorded with both live and sampled sounds, is cinematically grand to match the multimedia systems on which people are now playing the games. Throbbing, moody percussion underscores a scene onboard a spaceship, and other elements are introduced as the adventure progresses: The “aaahhhh” of an ethereal choir joins the percussion when (and if) a certain corridor is entered; a stinging string lick pops up with the appearance of an alien. O’Donnell also added lush mood-setting music to the menu and game-loading screens, as a film composer would to titles and credits. Released on CD, Halo is the first game soundtrack to be submitted for a Grammy nomination, in a category devoted to film and TV music that had to be stretched to “visual media” to accommodate it.

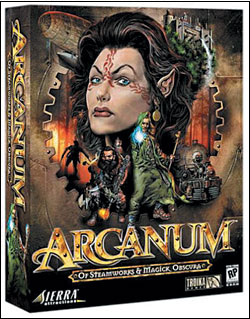

Fifty years ago, avant-gardists like Earle Brown and John Cage were leaving the ordering of musical events up to the players. Now this once-arcane technique is being used by game composers for far more commercial purposes. Composers call it “branching music”musical themes or tags linked to specific game events, designed so that any tag can lead un- jarringly to or from any other tag, creating a continuous flow, whatever the player’s choices. One way to do this is to strip down the texture at the beginning and end of each section, leaving just a rhythm or a bare drone; this facilitates the smoothness of the juxtapositions (like the way a club DJ segues from one dance track to the next). For the role-playing game Arcanum, Ben Houge wrote several separate sections of music, 50 minutes total, that make a satisfying continuity no matter how they’re shuffled. At the symposium, the Odeon String Quartet performed a suite from the 18 sections of Houge’s score, which Houge allows musicians to play in whatever order they like.

Scott Selfon, an audio content consultant for Microsoft’s Xbox, uses this same technique: recombination and repatterning of short musical cells. The composer models he mentions are Philip Glass and Steve Reich. “A lot of times you have to work with some very, very small elements, whether samples or small loops, so you end up developing some minimalist techniques. . . . I was writing basically orchestral music using samples, but in a way that was very nonlinear.”

Period settings are common in the game worlddesigners are letting their historical imaginations run wild, so a game composer needs a mastery of the widest possible variety of styles. The theme of Arcanum is the conflict between a medieval, magical, quasi-Tolkien world and warfaring technology circa the Industrial Revolution, so Houge chose the string quartet as an analogue, writing evocations of medieval madrigal style for a 19th-century medium, adding Romantic harmonic colorings. Yet just before Arcanum, Houge worked on a noirish urban game that called for jazzy Peter Gunn-style music.

The game business came along at the right time for these composers: Postmodern polystylism has been the most conspicuous trend in composition of the last 20 years. “It’s part of what you have to be able to do in film and television,” Selfon says, “and it’s taken to the umpteenth extreme in a video game.”