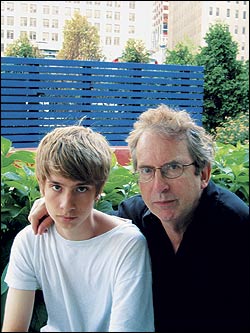

FOR A MAN WHO tells lies for a living, Peter Carey has a hard time keeping quiet about it. Tucking into sushi at a desolate lower Manhattan restaurant recently, the Australian-born, two-time Booker Prize–winning novelist confesses he has invented a character in his new travel memoir, Wrong About Japan: A Father’s Journey With His Son (Knopf, $17.95).

“To get to the argument and the conflict, I had to,” says Carey. “I wasn’t going to have conflict with anybody in real life. So I have this imaginary character do a whole load of things which didn’t happen.” That character is Takashi, a Japanese cartoon character Carey’s 12-year-old son, Charley, meets over the Internet. Takashi steps right out of Japanese anime, shimmering colors and all, and agrees to be their tour guide.

This literary device typifies what Australians call illywhacking, the invention of an outside voice to point out conflict. Introducing his visitors to famous Japanese animators and toy designers, Takashi is both emissary and cultural gauge; he’s quick to let Carey know when he has offended a cultural sensibility.

Which wasn’t all that often, Carey explains: “We had such a nice time. At various stages of the trip, Charley even said how happy he was—which is really unusual for him.”

In contrast to Carey’s hefty novels Bliss and Illywhacker, the slim, illustrated Wrong About Japan reads like a literary version of Sofia Coppola’s Lost in Translation, minus the melancholy and the stylish soundtrack. Carey and his son marvel at the way Japanese toilets flush; they joke that a man at a restaurant might be a gangster.

The trip and book came about, Carey explains, owing to his son’s obsession with manga, the Japanese comic-book form that sells in the billions. Every night, after 30 minutes of schoolwork, Charley would pull out his manga and read. Soon the father became interested, too, though without intending to write a scholarly work on the country: “If the book is going to have any value, it is not going to be about Japanese culture. Everyone was continually alarmed that I would presume to write anything about it—and they were absolutely right. The real objective was so that Charley could get pictures for his wall.”

SO HOW DID their visit go for father and son? To differentiate between his Japan and Charley’s, Carey promises he won’t subject Charley to the “real” Japan—of temples, tea ceremony, Kabuki—so long as he can do some of that exploring on his own. Meantime, Charley susses out the frivolous stuff—the video arcades and light shows and comic-book displays.

Yet the frivolous stuff turned out to be not so frivolous, as you’d expect from the historically minded novelist: “In Tokyo’s Harajuku district, one can see those perfect Japanese Michael Jacksons, no hair out of place, and punk rockers whose punkness is detailed so fastidiously that they achieve a polished hyper-reality. Takashi had something of this quality. He had black hair that stood up not so much in spikes but in dramatic triangular sections. His eyes were large and round, glistening with an emotion that, while seemingly transparent, was totally alien to me.”

Carey’s entire oeuvre has been about respecting cultural differences, not flattening them. For this reason, he adds, he even instated dialogue to show that he and his translator (an actual person, not Takashi) were not communicating well. “It seemed to me a more complicated truth about misunderstanding, and the correcting of misunderstanding.”

A cultural boundary also exists in Wrong About Japan between Carey and his own son. Born in Australia in 1943, the author grew up playing with Japanese occupation money. Charley, however, was born in the 1980s and grew up on American pop culture and globalization. (Today, the family resides in New York.) They got along fine on their trip, according to Carey, but Japan’s spell wore off after they returned home. Charley helped his father edit the drafts of Wrong About Japan, but within a year he stopped watching anime, and his fanaticism about manga cooled, too.

Yet Carey’s next novel is set in Tokyo, he tells me, and it’ll return him more directly to his signature themes of fakery, thievery, and authorship. He says Japan is one of the few places where a painting can disappear only to reappear with a (pseudo) legitimate provenance. You get the sense Carey could sympathize with such work.

Peter Carey will appear at University Book Store, 7 p.m. Tues., Jan. 25.