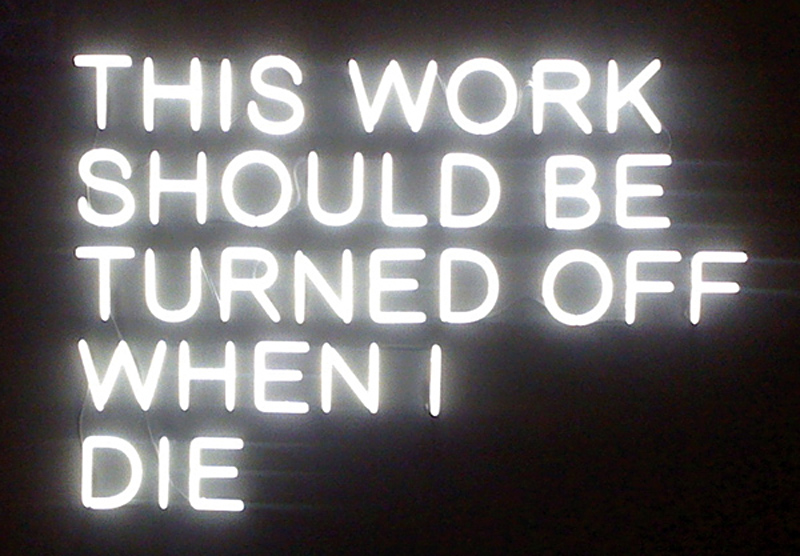

Philip Roth’s recent announcement that, at age 79, he was done writing brought both sadness and unusual finality. Artists seldom retire; they usually just decline and die, and their works outlive them. But a related thought occurs down in the basement of the Henry, where Now Here Is Also Nowhere features about two dozen artists from its permanent collection. Pace Roth, I remembered this recent neon piece by Mexican artist Stefan Brüggemann, its title spelled out in the image. Brüggemann is not yet 40, and we hope he lives a long time. But decades hence, will the Henry really unplug this work? Will it then be worthless? Would the piece then in effect be un-created and erased? Reading about Roth makes me think of Amazon, iTunes, and DRM (digital-rights management): the way content providers can pull the plug on your purchase after a given amount of time—or if they decide you aren’t the rightful owner. What if the plastic arts existed only during the short lifespans of their creators? It would be like having a grandparent who saw Nijinsky or heard Caruso live, something we epigoni could never experience ourselves. Brüggemann’s statement reminds us of the vast, unrecorded trove of human creation before writing, cave paintings, or mechanical reproduction. The world has lost far more art than has been preserved. Some artists command “Burn my letters after my death”—which their heirs ignore in favor of a Sotheby’s auction. You wouldn’t want Roth lost to posterity, but Brüggemann dares just that. (The show will rotate works in January, then continue into summer.)

The Fussy Eye: Terminal Art

Should it outlive its maker?