At least once a week, you’re likely to find Trimpin rummaging about the Boeing surplus store, or any number of places across the country where he seeks out obscure bits of technology. “I have a lot of sources,” says the diminutive, bearded man with stylish glasses and a slight accent. The singly named, German-born artist, who has lived and worked in Seattle since 1979, is an electronic sorcerer who creates kinetic sculptures that blur the line between technology and art.

A recipient of a MacArthur “Genius” grant in 1997, Trimpin has an affinity for strange combinations of technology. Player pianos and MIDI systems. Duck calls and tiny, electronically controlled bellows. Chicken-head bobber toys and random number generators. Like a kind of crazed tinker in his Seattle studio, Trimpin creates a jarring mix of the modern and the antiquated. And most notably, almost every one of his inventions makes noise.

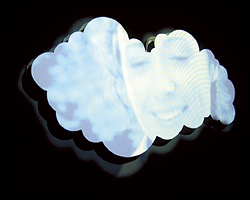

In the central gallery of the UW’s Henry Art Gallery through Oct. 2 (206-543-2280, www.henryart.org), a Trimpin piece first created in 1992 is making one hell of a racket. Its wonderfully onomatopoeic title is Phffft! (“It’s pronounced with a little crescendo at the end,” the artist says.) Shown previously at the Portland and Tacoma art museums, the electronically controlled piece employs some 200 various woodwind instruments—old organ pipes, reed instruments, and duck calls—to give space to sound. Arpeggios, blues scales, and Phantom of the Opera–like minor chords flit and swell about the room. Because each note is located in a specific space within the gallery, the piece has the astonishing ability to make the music seem to fly about. The piece also ingeniously lets visitors create very complex sound experiences with just two dials—or simply listen to one of 12 compositions Trimpin composed for the sculpture.

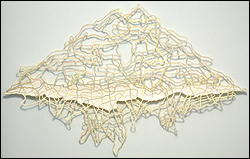

Locally, Trimpin is perhaps best known for the immense Roots and Branches sculpture at EMP, which robotically strums hundreds of guitars. Yet, except for that piece, Seattleites haven’t had much of a chance to see the artist’s work. But that’s all going to change in the next two years. The Henry show is the first of many Trimpin installations stretching through 2007 at local venues including Consolidated Works, Jack Straw New Media Gallery, Suyama Space, the Frye Art Museum, and Tacoma Art Museum. His national profile is also on the rise. Of late, a New Yorker reporter has been on his trail.

The driving force behind the Trimpin retrospective is Beth Sellars, curator at Suyama Space. One evening a couple years ago, Sellars was listening to Trimpin give a talk at Jack Straw, she says, “and I thought to myself—none of us have seen half of this stuff.” Sellars worked tirelessly to get a multivenue retrospective going, and is also working on assembling a book celebrating Trimpin’s 25-year career.

The artist’s résumé reveals an eclectic background: a youth spent studying various brass and woodwind instruments; technical training in electrical and mechanical engineering; and Berlin University studies in music and art. Nonetheless, Trimpin is modest about his technical skills. When I suggest he’s both an artist and an engineer, he demurs—”this isn’t rocket science.” That modesty downplays a formidable virtuosity melding science and art.

One of my favorite Trimpin works is a random foreign-policy generator, which appeared at CoCA earlier this year. It employed random number generators, chicken bobber dolls, computer software, and IBM typewriters to print snippets of Bush’s foreign-policy speeches. The Rube Goldberg–like contraption was the perfect metaphor for the seemingly random and illogical justifications for administration policy. But the genius of the thing was finding a use for those odd little alcohol-filled bird toys that bob and rise.

It’s the sort of improvisation that’s a Trimpin trademark. In the installation at the Henry, Trimpin marvels at some of his finds: lampshades double as horn bells, and the little valves that blow air into each instrument are similarly prosaic. “Restaurant fruit juice dispensers,” he says proudly.