“That’s one of my big points in making any game, creating worlds that people want to spend time in.” -Kevin Maxon

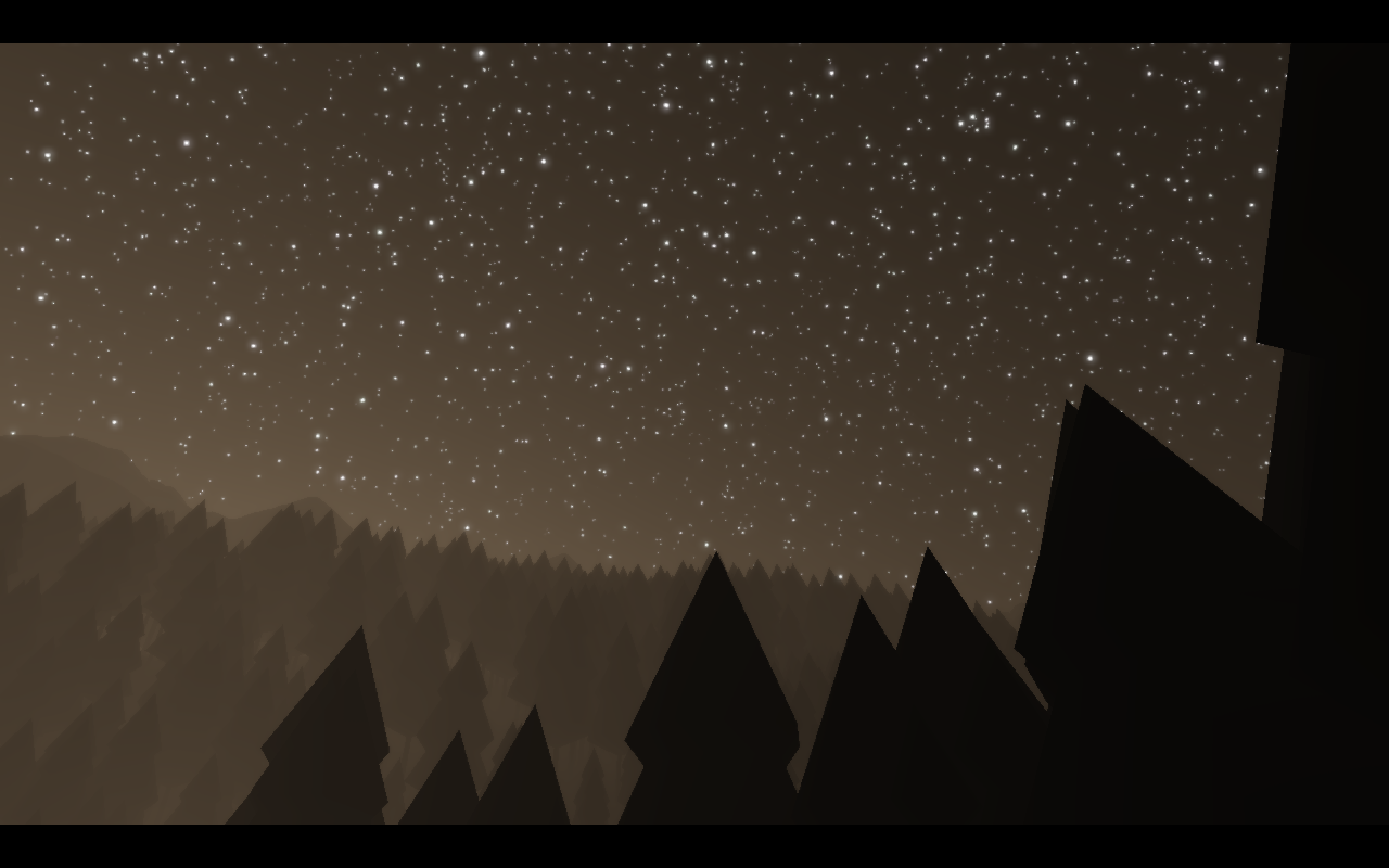

When you boot up Eidolon, you are plopped directly into a vast polygonal forest, somewhere between Bellevue and Olympia, with zero explanation. There’s no stage-setting, no tutorial, nothing. It’s just you and the “post-human” wilderness expanding in all directions around you. Your only clear objective is to survive. You have to eat—by hunting, fishing, or gathering berries and mushrooms—and you have to keep warm. Beyond that, interpreting how and why all the people have disappeared is up to you.

“The wandering was a big part of our interest in not having a linear game,” says Eidolon’s 23-year-old creator, Kevin Maxon, of Seattle. “We just wanted people to be in this place and enjoy this place. That’s one of my big points in making any game, creating worlds that people want to spend time in.”

Maxon initially began creating Eidolon as his final thesis project for a game-design degree at Western Washington University in Bellingham, where the woodsy setting reinforced the game’s outdoorsiness. As both a student and player, Maxon liked testing the limits of what the word “game” meant. He wasn’t content to create straightforward platformers, shooters, or dinky Flash-based RPGs. Instead, his early tinkering included one prototype where players manipulated shapes in response to Gertrude Stein poetry.

“There was this debate that’s kind of dead now,” Maxon explains, “but it used to be the only thing people talked about in game academia—it was between whether games are primarily systems or whether they’re primarily stories. Like, is Final Fantasy even a game? Some people were coming at it from a chess angle; some people coming at it from a theater angle—games more like Myst. It came down to whether people thought those things were valuable or not. I was trying to find a way to reconcile those two, because I’m really interested in systems, but also in how we can restructure storytelling in games.”

Some people would have a hard time calling Eidolon a “game.” Although you can buy it for Mac and Windows ($15, icewatergames.com), it feels more like a digital interactive painting—perhaps the love child of local landscape artists Cable Griffith and Mary Iverson.

I spent my first two hours playing Eidolon by slowly walking around the forest, clueless as to where I was or what I was supposed to do. I climbed mountains; I shot a fox and cooked its meat—sorry, vegans!—over a campfire; and I thought about how quickly I would die, given my lack of real survival skills, in an actual post-apocalypse wilderness situation. I’d definitely just gorge on blackberries and hope for the best.

It wasn’t until I stumbled upon a diary entry in Eidolon mentioning “the fall” and a siege upon Bellevue that the game’s fascinating pre-apocalyptic history began to emerge. Then I began to get my bearings—discovering the towering ruins of Bellevue and a Space Needle-esque monument to the people who died in “the great quake” alongside the crumbling remains of I-90. By then I was totally engrossed. What happened here?

Eidolon, if you were wondering, is an ancient Greek word for “phantom” or “ghost.” Maxon explains that he took the name from a Walt Whitman poem, “Eidolons,” which he calls “the freeware version of the game.” He continues, “It’s all focused on what’s permanent and what’s not—the things that humans obsess over, these physical things.”

Somewhat like Alan Weisman’s surprise 2007 bestseller The World Without Us, Maxon invites us to consider how the natural environment will outlast civilization. What will survive, says Maxon, are “these ethereal Platonic ideas, these big capital-letter Ideas… that are actually permanent and actually immortal. I like the idea that people might be fucked, but the world’s not.”

Eidolon was developed over 20 months by Maxon’s start-up, Ice Water Games, and is the company’s first product. Besides being an experiment in “environmental storytelling,” he says the game attempts to mimic the meditative quality of hiking though our Northwest mountains and forests. Eidolon does involve lots of hiking, and its amazing music—like a cross between the post-rock noir of Godspeed You! Black Emperor and the quieter moments of Modest Mouse—furthers that meditative atmosphere.

Bearded 23-year-old designer Kevin Maxon makes games about and inspired by poetry.

Maxon says sales are already on track to pay for the game’s development and to fund new games. Early reviews have been positive, despite the fact that (as Maxon acknowledges) Eidolon challenges conventional game structure. Its look—blocky and abstracted—also sets it apart from the trend toward video-game realism.

“I wanted to find a way to render these huge expanses—you know, a giant forest or a tree-covered hill,” says Maxon. “But computers have a hard time rendering those things. So I messed around with how I could use the least amount of polygons to render an evergreen tree. I decided to take all the textures out. In the end, I actually thought it looked better.”

The minimalist graphics of Eidolon do have their own kind of splendor. The sparse visual detail allows you to project your own psyche onto the landscape, something I often found myself doing during the game’s long virtual walks. For this player, at least, in an unraveling real world that seems constantly to deliver bad news, Eidolon helps hone a very important 21st-century human survival skill: finding shreds of beauty in the desolation.