There are many good intentions to The Listening Room, perhaps 2,000 of them—the approximate number of albums Theaster Gates salvaged from an old Chicago record shop. They’ve been neatly shelved along the gallery’s back wall, where you can browse but not touch the faded cardboard sleeves. Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder, the O’Jays—these are bands from a now-distant time, when listeners white and black could listen to the same R&B tunes on the radio. To scan the names on the spines—but not the covers—gives you a warm, nostalgic shiver, and Gates’ archival project is strongly oriented toward the past, which we might as well shorthand as the ’60s (though Gates was born in 1973). Can you remember, can you dig it? The music? The new civil-rights laws? The Southern sheriffs turning fire hoses on protest marchers? And those endless sit-ins?

“What is the relationship between music and the political?” asks Gates in his artist statement. “What is the state of Civil Rights?” Visitors are supposed to mull such questions while browsing, listening, and—from a smaller, separate group of records and a turntable—supplying their own soundtrack in the gallery. There’s furniture for lounging, all similarly salvaged, and an old church altar has been repurposed as a DJ console (for First Thursdays and SAM Remix events). It takes a while to realize that the light brown strips of cloth on the walls, arranged something like large flags, are made of fire hoses. (Not the ones Bull Connor used in Alabama, but hoses still.) This exhibit isn’t overtly political, and Gates’ statement—copies are located at the entryway—is hardly a manifesto.

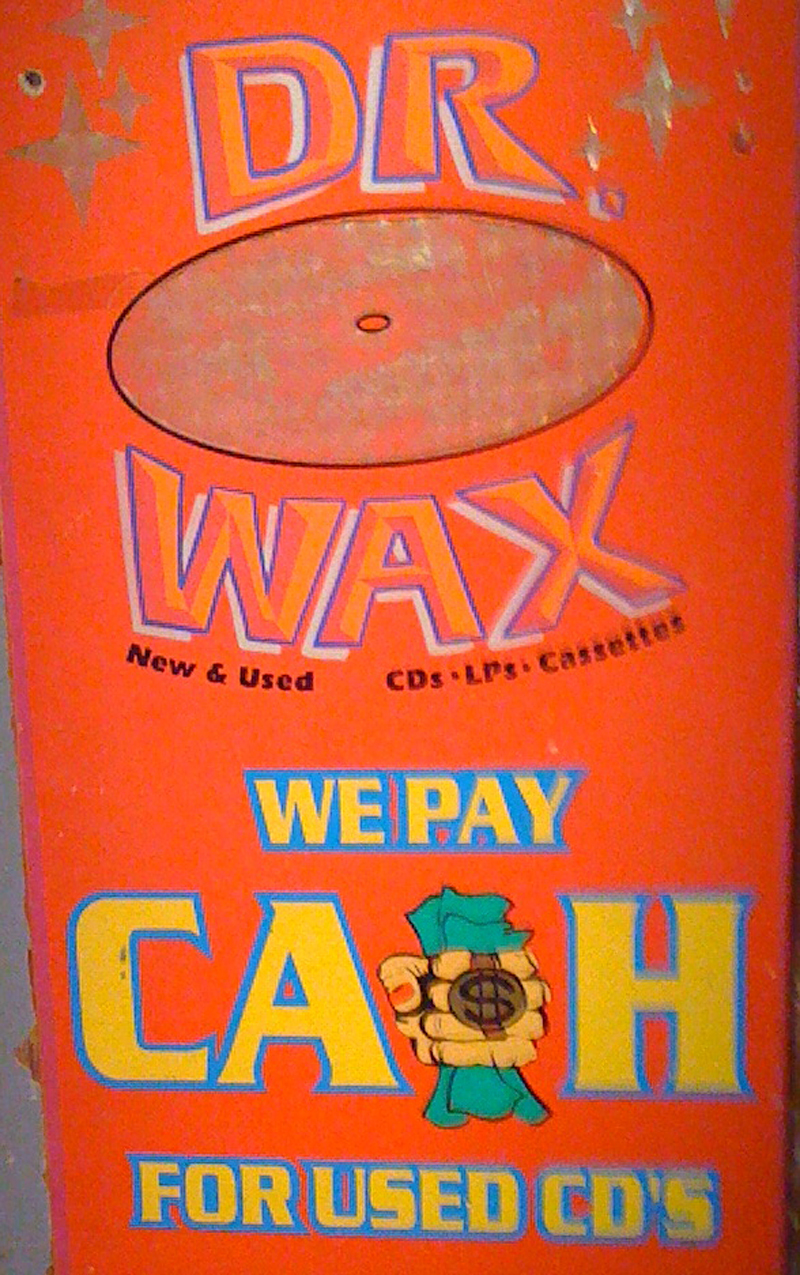

Indeed, during a press tour last month, the soft-spoken artist talked about creating a room to foster dialogue about “race and class and space and hope,” the notion being that music could open up museum visitors to such social engagement, rather than silently staring at art on the walls. He lamented how the old Dr. Wax record store, located in the Hyde Park neighborhood from 1984 to 2010, had once provided such a refuge during his youth. He compared its outdated, unwanted vinyl collection to the contents of a corner bookstore—”discarded knowledge” that he had rescued. “An archive, a canon,” he called it. The old Dr. Wax has been “replaced by a Chipotle,” he tartly noted.

For Gates, store owner Sam Greenberg epitomized the old solidarity of the civil-rights era. Even if he wasn’t marching on Selma, here was a Jew operating a store featuring African-American music in a traditionally black neighborhood. Thus, preserving Greenberg’s old wares became a way of preserving that past idealism. (For his part, Greenberg might not have seen his old business in quite the same way. “There are just not enough customers,” he told SoulTracks.com. “Downloading hurt us, but the economy put us under.”)

And who doesn’t nod their head at such noble sentiments? Who isn’t in favor of racial harmony, singing to the oldies on the AM dial, and recycling building materials? But after Gates delivers his modest remarks and exits the gallery, one is left with the installation itself.

Most of us have this music at home—at least some of it. Or we can download it, perhaps taking notes from the “don’t touch” albums for iTunes later. And turntables, honestly, aren’t such a novelty. Kids today know what vinyl is; and if they want to handle the stuff, a flea market is cheaper than SAM. (Plus you get to take the music home with you.) And will older visitors, who possibly still have their original album collections, really want to disturb etiquette by playing music here? I doubt it. Museums are for quiet contemplation; and there is in fact a dialogue in looking: what the artist has put before you, and your response to it.

Gates has used the fire hoses before (coiled, framed, arranged like sculpture), but on the wall they’re just bland swaths of beige. The originals from Birmingham might have some force, but these untitled pieces just read like wall covering. Given a little color, they could be carpets. The recycled furniture—from old Chicago factories, now closed—is no more impressive, and Gates makes no link between the decline of manufacturing and the decline of R&B and soul. The old signage is just random.

In the end, though a generous, sincerely communitarian gesture, The Sitting Room seems an exercise in nostalgia. One man’s unsold inventory is another man’s private utopia.