EVEN IGNORING THE WHOPPING balance sheets of Bill Gates and Paul Allen, the region’s greatest average wealth is on the Eastside. Yet very little of that prosperity has been channeled into sophisticated architecture or place making. The reasons are many: The high-tech world is more virtual than tangible (why isn’t Microsoft’s campus one of the world’s great building ensembles?), new money doesn’t often produce adept artistic patronage, and suburbia is not the best incubator for public-realm architecture.

A few days ago this state of affairs changed, at least symbolically, when the Bellevue Art Museum opened its new building with a big party just as one millennium gave way to another. Its 36,000-square-foot structure is tiny in the presence of its overscaled downtown Bellevue neighbors: a Pentium chip of intense design ambition in the midst of poky 286 processors.

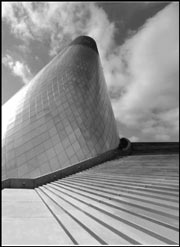

BAM is a cheeky, red, concrete low-rise that makes no concession to the visual world of the huge shopping mall, corporate towers, and large parking lots nearby. It is the work of Steven Holl, a Bremerton native and University of Washington architecture graduate who moved to New York to become an avant-garde theorist and designer. In 1997 he captivated the local architectural community with his highly sculpted, ingeniously lit, and quietly poetic St. Ignatius Chapel at Seattle University.

Compared to the chapel, the museum is less self- conscious, more cost-effective, and more complex in function. It has a nice generosity of scale and fluidity of internal space. Like Holl’s recent Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art in Helsinki, it is planned around a large central atrium. Here that inner space is called the Forum, and it will serve as a gathering and performance zone as well as the museum’s circulatory heart. Adjoining it are a small auditorium, a museum store, and the most visually understated Tully’s cafe on the planet. This first floor is fully public and can be entered without paying admission. Tully’s seating will spill onto the sidewalk of NE Sixth Street, bolstering Bellevue’s optimistically designated pedestrian spine.

Spiraling up clockwise along the atrium’s curving walls, a gently sloped cantilevered stair leads ceremoniously to the second floor, which houses administrative offices, classrooms, and the Explore Gallery, an interactive display area. It then continues to the third level, where the main galleries and more classrooms are located. In the process, it disappears from sight because the atrium is only two stories high; the space above it is the largest of BAM’s six roof terraces, and its paving limits the atrium’s natural lighting to a trio of modest circular glass discs. In compensation for the reduced daylight, Holl has devised some ingenious and handsome methods of artificial illumination, including the undersides of the stairs, which were unfinished at press time.

The terraces all have names and themes. (Holl likes to cloak his buildings in stories, metaphors, and fables—some real and some fanciful.) Two of the terraces, along with the underside of the main entrance, will eventually be enlivened by projected still and video images after dark.

The interiors are minimalist and often elegant, with black floors, primarily white walls, debatably textured plaster ceilings, and ash wood doors, trim, and perforated wall panels. In the top-floor galleries, greenish glass-channel strip windows hover high atop the walls. The detailing is inconsistent, however, as evidenced by the main stair’s thin pipe handrails, which are pleasant to neither the eye nor the hand.

Among the new local museums of the last decade or so—the Seattle Art Museum and its renovated Asian art satellite, Tacoma’s Washington State History Museum, the Henry Gallery, and even the exemplary reworking of the Frye Art Museum—this is the second most ambitious piece of pure architecture. (Frank Gehry’s wildly expressive Experience Music Project leads the pack.)

HOW WELL BAM performs as a museum is less clear. The jury will be out for at least a year regarding the question of how well its quirky spaces work for the museum’s shows, classes, and events. The partially installed first shows suggest that mounting exhibitions will be a challenge in BAM’s fragmented, narrow third-floor galleries because of their difficult configuration and their abundant daylight. (Standard art museums take pains to exclude 99 percent of natural light to protect the more delicate of their artworks.)

But BAM is not a standard art museum. It has no permanent collection, and much of its energy goes into community-oriented programs such as art classes, artist-in-residence programs, and public events. For Holl, the lack of a collection made the project “more exciting because it’s mysterious.” Paradoxically, the exhibition spaces he provided don’t seem as flexible as one would expect for galleries meant to accommodate the unknown. Artists, curators, and installers will have to adjust to the design rather than being aided by it. Even before opening, BAM swallowed hard and revised part of Holl’s layout by extending one of his gallery walls. This conflict between pure architectural expression and the demands of exhibition is a frequent problem in contemporary museum design, and one that Holl perceives when assessing other architects’ efforts.

BAM recognizes that a suburban museum is a different animal than an urban one, and that perception previously led it to take up quarters in the Bellevue Square megamall across the street from the new building, reasoning that this was where the people were. (Its earliest quarters were an old schoolhouse and a former funeral home.) But the mall location, undersized and isolated on the third floor, didn’t provide the operating space, visibility, and foot traffic needed for real success.

Ironically, the suburban location strategy wasn’t effective, so now BAM has adopted a more urban approach: a compact cube, more or less built to the property lines along the main streets, entered from the sidewalk rather than from a parking lot. Without a context of adjoining buildings fronting the street, the building had no need to respect an established streetscape. Holl devised an asymmetrical set of exterior walls whose irregular openings and notches accommodate an entry porch, windows and clerestories, hand-sanded marine aluminum panels, and six rooftop terraces. In retrospect, this highly eventful design seems a bit overworked; a simpler conception with less plan fragmentation and fewer terraces might have better served the institution’s functions and freed up funds for some better interior materials and detailing.

Undertaking this project was a monumental act of faith. By expanding its space fourfold, BAM committed itself to a tripling of its staff and a major increase in programs and operating expenditure. It supported Holl’s personal vision wholeheartedly. He avows, “A good client is the best thing you can have.”

Architecture is an inherently imperfect art, and the museum and the designer did well in this project. But its principal accomplishment may turn out to be urban rather than architectural. BAM adds a much-needed pinch of leavening to Bellevue’s core, providing it with public space that is not commercial and increased cultural activity in a zone that is otherwise all business. With his lively and challenging building exterior, Holl has offset some of the district’s upscale banality. By building largely to the limits of the site and putting parking underground—tactics that were dictated by the small site as well as by civic concerns—the architect has produced, in his own estimation, “a prototype for urbanizing a sprawling suburban zone.” (Like many of his statements, this should be taken metaphorically and not literally.) BAM cannot and should not be copied, but the notions of urban compactness, enlightened patronage, and imaginative architecture deserve to take deeper root in the heart of the immensely wealthy Eastside.

Read Anna Fahey’s preview of BAM’s first exhibitions.