Nobody wants to call a group show a group show, because that sounds too dull. If there are a dozen or more artists working in diverse media and styles, how can you possibly put a unifying rubric on the mob? Still, it has to be done. Over at SAM, we get the idea: Elles = female. Simple. The Frye’s new all-local exhibit takes the opposite tack in labeling its omnibus Mw [Moment Magnitude], “the scale used by seismologists to measure the size of earthquakes in terms of energy released.” (It’s the successor to the Richter Scale.)

Got that? Are you ready for some science? Look out, Burke Museum, the Frye is coming after you!

But this is not to be. There is no science in the show, which involves about two dozen artists and performers, and there is no math. I seriously doubt anyone involved could explain a logarithmic scale. Artists sleep through geology class because they were up late creating stuff the night before.

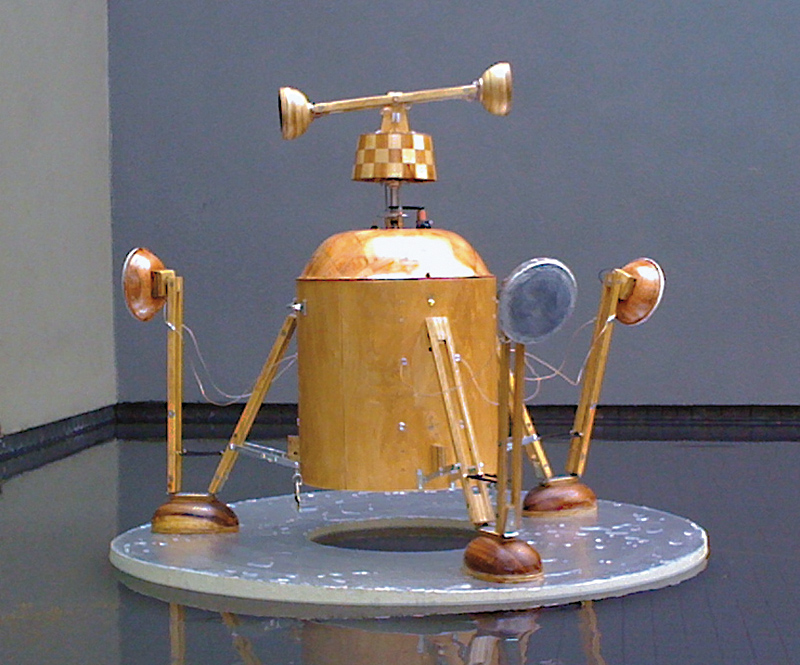

So get past the recondite name, ignore the word-salad wall cards purporting to explain each gallery, and you’re left to look at the art—good and bad, old and new. (For the music and performance schedule, see the Frye’s website.) Pause before you enter the museum, and you’ll notice a robot careening around the reflecting pool. Built by Robb Kunz, gently playing music by Jherek Bischoff, it’s like an aquatic cousin to R2-D2 and WALL•E. It’s an endearing little bit of mad science that has you wishing for more of a laboratory to follow. (There’s an easy theme for you—robots!)

Inside, one of the best and weirdest pieces hangs from the ceiling. It’s a fiberglass rendering of Saddam Hussein’s famous “spider hole,” cast from its outline like a bright yellow cocoon by Leo Saul Berk. Negative space has been reversed, so that the gallery corresponds to the ground and the ceiling to the surface. This Spider Hole seems oddly divorced from history (has it really been nine years since the war began?), an object wrenched out of context. All you’re left with is the bizarre form—like some historical ghost, a forgotten term of war like Maginot Line or Gulf of Tonkin. (There’s another ready-made theme—war.) I also like Berk’s glowing green light-box photos taken through the uneven brickwork of a childhood home in Illinois. They too have a subterranean aspect, like catacombs.

There’s also a desolate quality to the photographs and ceramics of Buster Simpson. In one shot, taken in 1974 in Post Alley, he’s depicted like a peasant foraging for firewood in the rubble. The scene could be 1946 Berlin, Sarajevo in the ’90s, or Kabul today. (Or the cover of Led Zeppelin IV.) Simpson also ventured into environmental art during the ’70s, depositing china in the polluted tidewaters of Elliott Bay and beyond, then removing it 18 months later to re-fire in a kiln. The toxic abuse and degradation are thus preserved, and you could possibly eat off these dishes today—maybe even serve fish caught from Puget Sound, so much cleaner now.

From the ’80s, Cris Bruch’s shopping carts and hobo camp also feel like politically engaged artifacts. (Theme alert! Consumerism and Its Discontents.) One of Bruch’s most striking carts, wrapped in steel like a miniature tank, greets you in the Frye’s rotunda entrance. Attention Shoppers would be useless at Safeway, since you can’t put anything in it, but there’s a kinship to Kunz’s Andromeda Strained floating outside. Both seem like objects that might outlive their creators and outlast civilization—or maybe it’s just Superstorm Sandy that’s got me thinking that way. (Disaster Art, anyone?)

Moment Magnitude is intended to celebrate “Seattle as a global epicenter of creative activity,” and it concludes the Frye’s series of 60th-birthday events this year. It would’ve been too obvious to do a ’52/’12 juxtaposition of art created back when and today; that approach would’ve yielded no more (or less) quality than Moment Magnitude, which feels cacophonous with too many music videos and cluttered with dull detritus. There are no shocks here, only a few welcome tremors.