A few Tuesdays ago, Seattle Symphony musicians gathered for their first look at Aaron Jay Kernis’ On Wings of Light, slated for a premiere two days later. Most of the players were wandering back onstage after a short break, following a dig into Dvorak’s Seventh, but the trumpets stayed behind to rehearse licks—fast, brilliant, demanding triplets. Conductor Gerard Schwarz stepped onto the podium.

“Under tempo,” he announces before giving the downbeat. Even so, the notes hurtle by; it’s hard for me even to keep up turning the score pages. Full of sparkle and brassy, Bernsteinian syncopations, the three-minute piece is glitteringly chaotic, as if Kernis had somehow emptied a barrelful of ear-tickling sounds onto a sheaf of score paper. He throws the orchestra one curveball—a broadening of tempo, then a snap back to the original speed, all in one bar. Schwarz stops the orchestra to dissect and explain. Quick studies all, the players easily pick up the rhythm on a second pass before Schwarz continues from there to the end. “That’s all—see you tomorrow.”

This run-through, the first hearing of On Wings of Light anywhere, is a scene the orchestra is repeating 18 times in the new season running through next June. Whereas a normal SSO season might include a premiere or two among a half-dozen contemporary works, Schwarz’s final season as music director is being marked with a surprisingly massive undertaking. Named for its funders, the cycle of Gund/Simonyi Farewell Commissions comprises new pieces by 18 composers, including composer-in-residence Samuel Jones, Daron Hagen (whose Amelia Seattle Opera launched in May), and familiar names like David Stock and Bright Sheng.

Learning so many new works is a challenge for all the players, but “as a percussionist, we have unique issues,” says Michael Werner, SSO’s principal percussionist. For one thing, contemporary composers tend to write percussion parts vastly more prominent and difficult than those in older music. Also, while a SSO violinist, for instance, plays only the violin, and generally uses the same one for every performance, percussionists have to master dozens of instruments, and select just the right specimen for each piece to fit the musical big picture. (For any given triangle part, Werner can choose from among the nine he owns.) And these decisions can’t always be made in advance: “Sometimes even looking at the score, you can’t really know how you fit in,” says Warner. “You can guess what a composer intends, but until you get in there, you don’t know.” After his first run-through of On Wings of Light, for example, Werner decides to switch to a smaller bass-drum beater to make a brighter, tighter sound more apropos for the fast tempo.

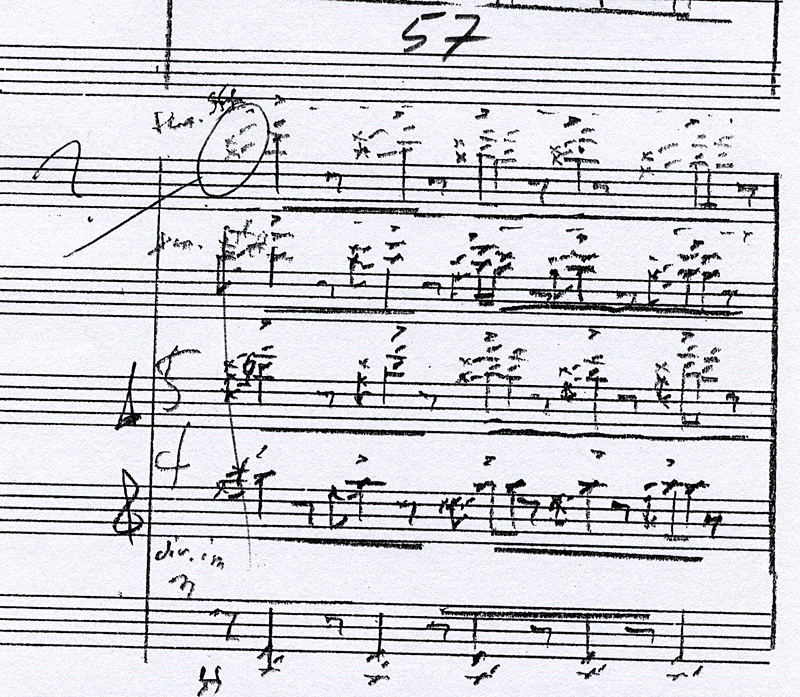

Copyist Rob Olivia, SSO associate music librarian, is also working harder than usual this season. On his desk is a list of the 18 commissioned works; next to some is the notation “everything,” meaning that for these pieces it’s Olivia’s responsibility to prepare the score and parts. Some composers have provided these materials themselves. Others, due to the looming deadline (the composer lineup was just finalized this summer), have given the SSO only a pencil manuscript.

Right now Olivia is using Sibelius 6, state-of-the-art music-notation software, to work on David Stock’s Blast. The first performance is November 4, and the players are (contractually) entitled to get their parts two weeks before the first rehearsal. Olivia received Stock’s score on September 20, but the quick turnaround doesn’t faze him after years spent working in Hollywood, where he sometimes had less than a day to extract parts from a film composer’s manuscript. With a career based on new music (he’s also Schwarz’s preferred copyist for his own compositions), Olivia is brightly enthusiastic about this project—and moved, too: “These are gifts,” he says of the commissions, “outpourings of gratitude for [Schwarz], who’s done so much for American composers.”

Not all the 18 composers will visit Seattle to hear their works performed, but Jones, in his 14th season as SSO composer-in-residence, will definitely be present at this week’s rehearsals and Saturday’s premiere of his Organ Benediction. (It’s a reworking of the ravishing Benediction the SSO recorded on its recent Echoes CD.) If this season’s series of premieres becomes business-as-usual for the players, it’ll remain a unique experience for each composer.

“It never fails to be overwhelming,” Jones says of the process of turning a composer’s dots and lines on paper into audible reality. “There is a certain almost-miraculous experience, the first time you actually hear those notes you’ve been thinking about. You hear them in your head, of course, and the more experience you have, the more you know what’s about to happen. But hearing the piece in your head and then hearing it live is analogous to kissing your wife over the telephone. The real thing is so much better.”