“People were very uncomfortable showing it,” says Robert Levenson of the decorative art and design objects he began collecting some 30 years ago. They came from an overlooked and possibly even shameful time. “There was a political problem,” he says, an historical stigma associated with the period and origin behind the traveling show Deco Japan: Shaping Art & Culture, 1920–1945.

Levenson made these remarks during his recent Seattle visit from South Florida (so full of pastel Deco hotels and such), where he and his wife Mary have amassed a trove represented here by about 200 items. It’s not fine art, nor do the Levensons—nor SAM, nor curator Kendall Brown of Cal State Long Beach—pretend otherwise. On display are posters, kimonos, postcards, ashtrays, furniture, vases, screens, and even matchbook covers (my favorite—more on that below). The Levensons’ focus is admittedly narrow and specific; they took advantage of a discount, in effect, created by the prewar taint of Japanese nationalism and militarism. Sometimes even bruised fruit can find a buyer.

Yet now, after most all the veterans of World War II are gone, it’s hard to see why that stigma exists. There’s nothing here like the swastika-emblazoned cigarette case your grandfather might’ve taken off a German corpse at Normandy. It’s possible to read the political codes of a few decorative items (the phoenix, say, might represent a rising Japan), but Deco Japan is about the advent of moneyed leisure time, not the winds of war. A vogue for Western fashions and stylish pursuits—golf! travel! skiing! movies! nightclubbing!—swept the fast-industrializing nation. And by nation we mean the factory owners, or more likely their sons, daughters, and courtesans: those with money to spend, passports, and free time.

There’s a nice consonance here between Carl Gould’s original 1933 design for the SAAM building, itself a Deco exemplar, and the Levenson collection. I’m not a fan of the low ceilings and cramped galleries of this obsolete structure, but its limits suit this show. The galleries are arranged by theme—nature, the modern woman, marine life, abstraction, home furnishings—with many of the small items in glass display cases. It almost feels as though you’re wandering through the estate sale of a rich, eccentric dowager who grew up in ’30s Kyoto. Some objects seem like sentimental keepsakes from the mantle, while others provide a flash of insight into forgotten times.

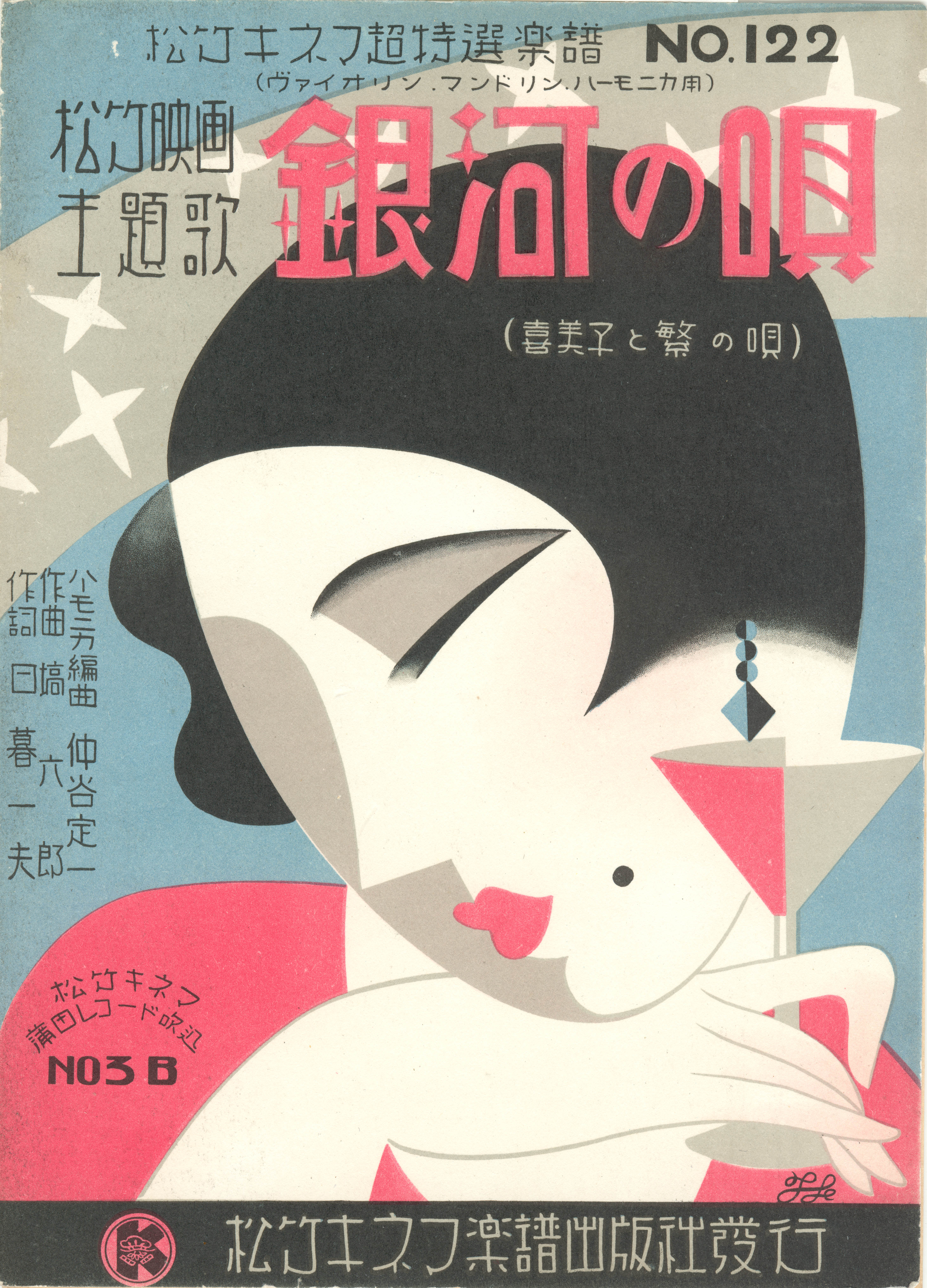

Two folded-paper cranes are actually plated with silver and gold. Robes are screen-printed with movie sets and the skylines of distant cities one might aspire to visit. A bright-red handbill depicting dancing, leggy chorines is actually a political leaflet. Boldly printed sheet-music covers promote songs like “The Modern Song.” On a traditional screen, a female skier stoops to adjust her bindings in a snowy tableau that’s both indigenous and imported. (Japan was to host both the Winter and Summer Olympics in 1940; those plans were interrupted by war.)

During the ’20s and ’30s, let’s remember, culture was transmitted by radio, movies, and magazines. Japan’s old isolation was—in the cities, at least—instantly erased by Marconi and Edison. Parisian salons were then already absorbing the Chinese and japonisme currents of the previous century; what they relayed back to Shanghai and Tokyo was both borrowed and new. The streamlined locomotives and black-lacquered secretaries’ desks conveyed both speed and simplicity; the old Gothic filigree and Renaissance piety were stripped away for the sake of nocturnal motion and pleasure. Adornment gave way to the 20th-century candor of essential form. Buildings showed their trusses; women shed their corsets.

For that reason, what’s most interesting here to me are the ephemeral, hedonistic traces of a demimonde that would soon be erased by war and the atomic bomb. Look closely at two framed sets of tiny matchbook covers—examples of low, cheap, disposable graphic arts—and you’ll see the bare legs, high heels, neon glimmers, bobbed hair, martini glasses, and cigarettes that symbolize Western “progress.” There’s a kind of forbidden allure that’s being absorbed into Japanese culture—the promise of cocktails, smoking, taxi dancing, and maybe something more in the rooms above the club.

One series of fan-shaped portraits comes from Tokyo’s posh “Florida” nightclub; the hostesses could pass as flappers with their smart young outfits, like distant cousins to Louise Brooks. They, like other women represented in the show, are moga, shorthand for modan garu (“modern girl”). If they couldn’t vote—that would wait for the postwar constitution, with a women’s-right clause written by the American Beate Gordon—they could at least smoke, drive, flirt, and wear Western fashions.

All these fleeting pleasures recall Japan’s Edo-period “floating world,” which preceded its abrupt opening to the West in the mid-19th century. The old Japanese elite had its homegrown decadence before industrialization. What Deco Japan celebrates is the new Jazz Age frivolity, a casting-off of the past. Japan was then in a hurry to catch up with the West. Pearl Harbor halted that progress, and its tokens were packed away in steamer trunks that the Levensons and other collectors would open a half-century later.

bmiller@seattleweekly.com

SEATTLE ASIAN ART MUSEUM 1400 E. Prospect St. (Volunteer Park), 654-3100, seattleartmuseum.org. $5–$7. 10 a.m.–5 p.m. Wed.–Sun., 10 a.m.–9 p.m. Thurs. Ends Oct. 19.