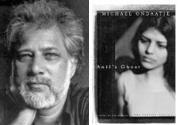

MICHAEL ONDAATJE’S LATEST novel, Anil’s Ghost, follows the story of Anil Tissera, a young forensic scientist contracted by an international human-rights group to return to her native Sri Lanka and investigate a rash of murders and disappearances on the island. Dismissed and diverted by local officials, Anil maneuvers beyond the sanctioned to unearth a more involved truth, transformed by encounters had along the way. With a story at times brutal and tragic, Ondaatje brings us an unflinching glimpse of one of the many oft-forgotten wars; far from ironic or condemning, Anil’s Ghost emerges as a quietly heroic story. I recently had the chance to ask Ondaatje about the novel’s origins and some of his own more intimate foibles.

Anil’s Ghost

by Michael Ondaatje (Knopf, $25)

FM: Whether it be the attraction to such notorious figures as Billy the Kid and jazz immortal Buddy Bolden or the somewhat familiar territory of the Second World War made ethereal, your earlier novels have a conscious approach by the author toward the material. This novel seems different. How did it come about?

MO: Rather than following a preconceived notion, the book grew directly out of the research. For instance, my encounter with emergency doctors in Sri Lanka led directly to their inclusion in the book. The impact of meeting a group of people so selfless was incredible—the expertise and focus that allowed them to exist within so much chaos. I met a number of people like this. They were like samurai or something. They didn’t give a damn about which party was in power or what new faction had arisen, they simply went in there and healed people. And they weren’t foreigners. We all know of Amnesty International or Doctors Without Borders, but these were locals. And this experience was a gift to me because I didn’t want to write about a country, my country, and leave it as something solely dark and vicious. So, the stories portrayed allow some virtue, [allow] the beautiful and courageous to accompany the tragic and senseless. The end of the novel and the small discoveries won are frail but real.

FM: You have taken a long path—through the Wild West, turn-of-the-century New Orleans, and WWII—to finally arrive at the contemporary moment. Did you find it more challenging to write without the romantic distance of history?

MO: Finally, I have arrived (laughs). I guess if I follow logic, I will be writing science fiction next. But, yes, this was certainly the most difficult book so far. When you are writing about a place still in the midst of tragedy and war you can’t be too facile. There is a real focus out there you feel responsible to, and yet, you don’t want to simply record history. Rather than heroes and villains or higher echelons of power, this book was about a state, the state of war, and how people continue on in it. But on a lighter note, I did also enjoy writing about the oddity and ease of something as contemporary as a cell phone, for example.

FM: Reality slips on various guises in the novel, shifting from forest monasteries to Oklahoma bowling alleys. There is a levity brought to the novel by Anil’s juxtaposed remembering of her life in the West—her passion for bowling and B-movies, Van Morrison lyrics. How much of these peculiarities are, in fact, really your own?

MO: Let it suffice to say that I have bowled. Van Morrison has come up in my work before, and I will admit that I was probably the first guy in Toronto to see Die Hard, for instance. But part of living with a book for so long is the pleasure taken in allowing the casual, the happenstance to take part. It’s somewhat like a play: You are in this room and someone might walk through the door at any moment. If you are too dogmatic, determined, or knowledgeable about what you write, then I think it turns out boring. Boring to yourself, at least. I always approach a novel wanting to learn about something. In this case it was archaeology and the study of bones. But this is what I’m referring to when I say that I have embraced the novel as a radical form, something far more open than Robertson Davies or Jane Austen. You want to be able to use photographs, song lyrics, interviews, quizzes, crossword puzzles, everything. Actually, I still haven’t managed the crossword. I’ll have to try that.