Pablo Picasso made the cover of

Time

several times, along with that of Life and just about every other major postwar periodical. But his fellow-traveler and countryman Joan Miro? Not so much. Both men established their reputations in prewar Paris, exhibited at major American museums and galleries, and lived a very long time, producing an enormous amount of art of varying quality.

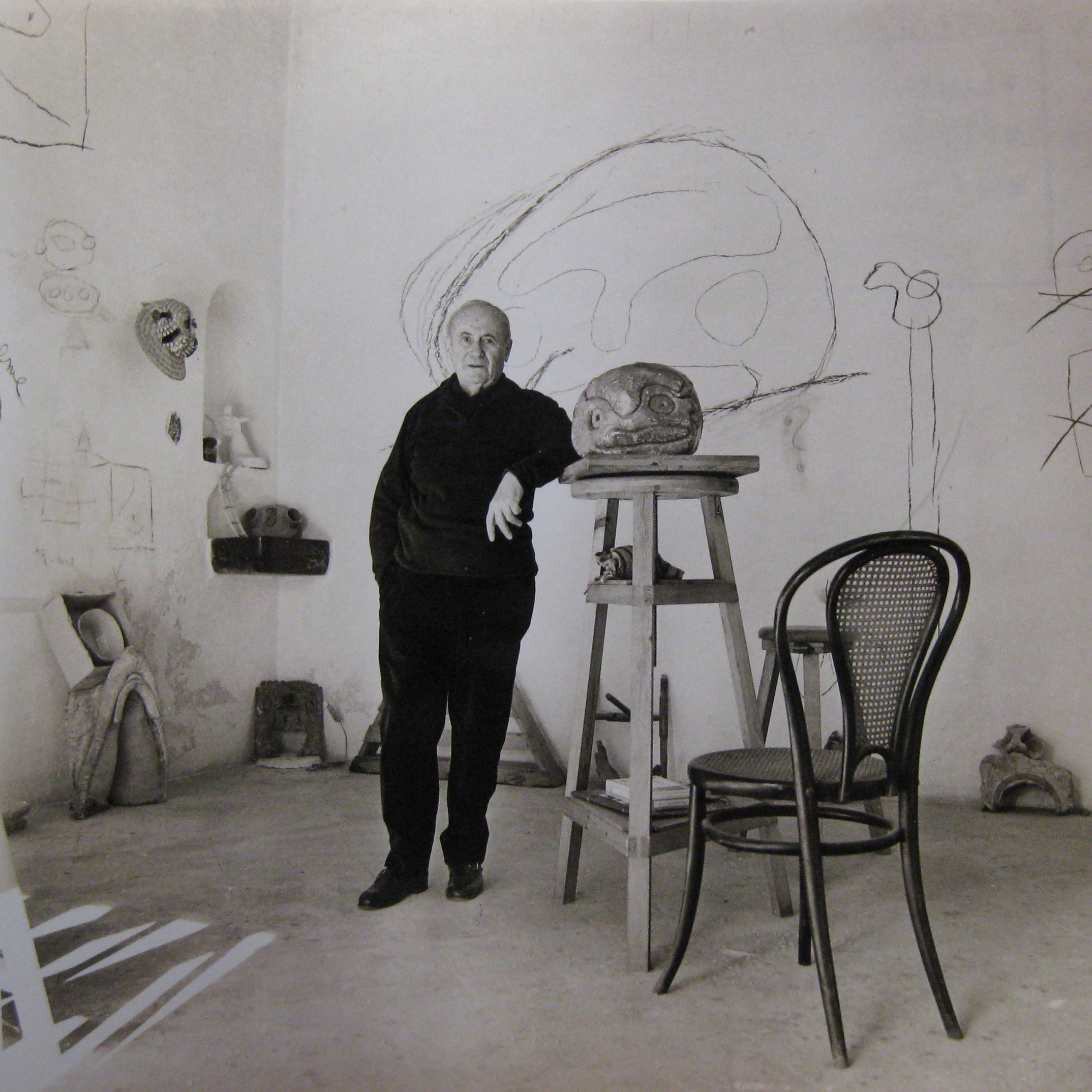

Yet three decades after his death, why has Miro (1893–1983) receded more in popular memory? Lacking the grand personality of Picasso (the art world’s first international celebrity), Miro somewhat controversially returned to Franco’s Spain following its Civil War, and made himself still more remote—if not quite a recluse—by moving to the island of Majorca in the mid-’50s. Though he had shows at the MoMA in 1941 and the Guggenheim in 1972, and though he visited the States a few times, Miro kept close to his studio during the last two decades of his life; and that period provides the 50-plus works in the Seattle Art Museum’s traveling show Miro: The Experience of Seeing, launched from Madrid’s Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia.

Miro, such an influence on Alexander Calder, was once part of the mainstream art lexicon. Do you remember those folk-music-loving academics who sheltered the hero of Inside Llewyn Davis, they with their book- and art-filled Upper West Side apartment? They would’ve had Miro prints on their walls, reproductions of his signature works from the ’20s and ’30s. Back then, Miro mixed with the Surrealists, but broke with them; there are also elements of cubism in his whimsically organic and abstract early paintings; and those lineages persist in the canvases we see here. Still, these aren’t the works that defined him, that made his reputation.

Miro was recently granted a big retrospective at the Tate (in London), which traveled to our National Gallery (in D.C.) to much acclaim. But that assessment went back to his roots, while the Madrid curators seem determined to say, Look! There’s more to Miro than his early years! I’m not sure that’s true, though Majorca is certainly a nice place to visit.

The best things here are familiar: Miro’s large canvases in a few primary colors, hinting at natural forms (women, birds, constellations). These aren’t wholly abstract or purely expressive paintings, and their titles are strictly referential. The big dark blob of his 1977 Head, Bird may not suggest a bird on wing, but there’s the hint of a beak and a jittery, avian energy—like a bird on the ground, scampering for seeds. The contours are there, if not the exact shape, and that’s how Miro depicts women, too. There’s hardly a straight line in any of his paintings, because the organic always meanders, like a sparrow’s flight or a tree’s branch or a woman’s hips. (However, his putting a bird on everything does inevitably remind you of Portlandia.)

You see all those tokens in an early key work like The Farm (not on view here) from the ’20s, famously purchased by Hemingway, which includes all of creation in a simple barnyard vista—animals, women, earth, sun, and sky. In that scene, there’s a transcendence from the mundane and material; a half-century later, Miro keeps refining and abstracting the natural world into the spiritual (though not Christian) realm. The tree that anchors The Farm, with is branches grasping ever upward, reminds me of Miro’s later line-work—rounded, unbalanced, somehow teetering—that you’ll also see in Woman, Bird and Star (Homage to Picasso), the large image that dominates this show’s first gallery. “Movements have no end,” says Miro on one wall card, and his brushstrokes have that kind of expansiveness, as if reaching beyond the picture frame.

If anything, Miro was maybe too well absorbed into the postwar art vernacular—meaning not just Calder but illustrators like Jim Flora, with their cheerfully bright-colored pendants and doodles and squiggles (most, however, ceasing to reference our known world). It’s no slight to say that most of Miro’s paintings would look great as rugs. They have a welcoming, homey kind of abstraction. The shock of the “primitive” has faded after a century.

New to me, and I suspect to most visitors, are the cast-bronze sculptures Miro made from found objects he gleaned on the beach and elsewhere on Majorca. They’re totemic, tabletop-sized objects that incorporate nails, baskets, an oven door, rakes, spoons, metal knobs, barrel hoops, and other detritus. They correspond to Miro’s 1941 memo to himself to create “a truly phantasmagoric world of living monsters.” Now Picasso knew something about monsters (i.e., women, as he often rendered them), and these are not monsters—they’re too friendly and apprehensible for that. Again, they bear figurative names and vaguely suggest natural forms, but they don’t compare to the paintings here. They’re an odd little footnote, a cul de sac gathering of strange small assemblages that seem sprung by the artist’s caprice—look what I can make out of random objects!

Still, as with the paintings, there’s an impressive vitality for an artist working to the age of 90. You’ll see that energy here in a 25-minute video interview with Miro, filmed in 1974. “I never dream,” he quips. “But when I am awake, I am always dreaming.” This modest selection of work makes you want to see more of those dreams, the whole of his career—but one would have to visit Madrid for that.

bmiller@seattleweekly.com

SEATTLE ART MUSEUM 1300 First Ave., 654-3121, seattleartmuseum.org. $12.50–$19.50. 10 a.m.–5 p.m. Wed.–Sun., 10 a.m.–9 p.m. Thurs. Ends May 26.