PA Band Called Death

runs Fri., June 28–Thurs., July 11 at SIFF Cinema Uptown. Not rated. 98 minutes.

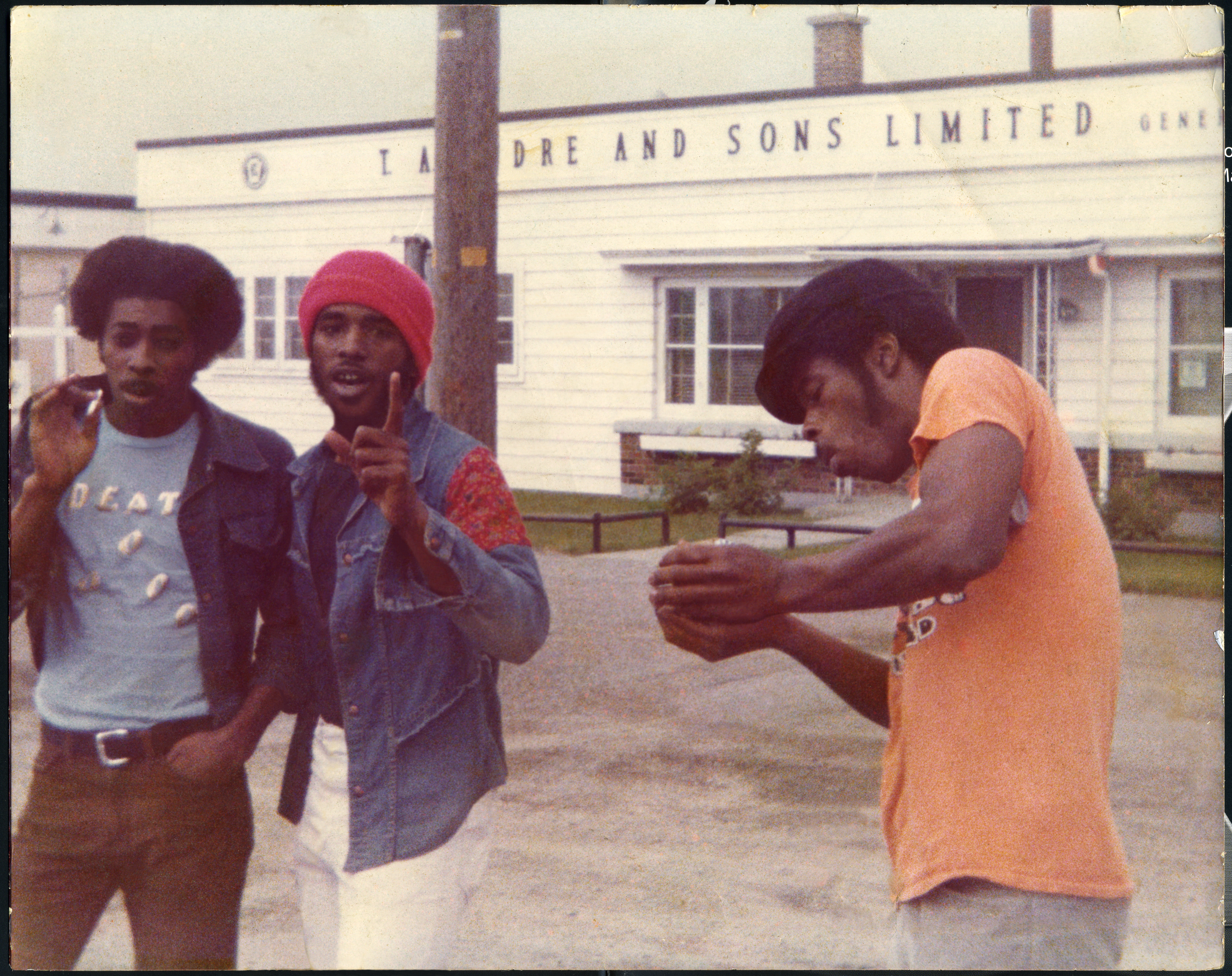

Thirty-seven record-store clerks feared dead in Yo La Tengo concert disaster. I’m quoting The Onion’s famous fake headline, of course, and that’s not what happens in this doc about three forgotten Detroit punk-rockers of the early ’70s. Yet it’s a no less vinyl-centric tribute to an even more obscure band. Death was founded by African-American brothers David, Bobby, and Dannis Hackney. The Detroit trio recorded and pressed one 1976 single on spec; no label would sign them; and the 45 was relegated to used-record bins for more than three decades—coveted only by obsessive collectors of vintage wax (far too many of whom are interviewed here). Then came Mike Rubin’s 2009 story in The New York Times, and Death was miraculously revived from the dead.

Vermont directors Jeff Howlett and Mark Covino were astonished to find that the surviving Hackney brothers, Bobby and Dannis, had been fronting a popular Burlington reggae/jam band for years. More incredible still, the next generation of Hackney kids were themselves musicians with no idea of their elders’ rock roots. (“Dad, why didn’t you tell me?!?”, one son explodes.) A Band Called Death is the irresistible, poignant tale of how the Hackneys finally got their due: three black kids who predated the MC5, the Stooges, and the Bad Brains; a band now praised by Jack White, Kid Rock (“How did I not know about this? This is bad-ass!”), and Henry Rollins. You might not want to hear their songs over and over again, unlike the easy FM melodies of Searching for Sugar Man, but their tale is no less genuine and affecting.

Rotoscoped old stills mix with new interviews; geeky white record collectors share their passion for Death; but it is the Hackneys who deservedly dominate the show. David emerges as the group’s Brian Wilson: a troubled, kooky spiritualist who declared “The ultimate trip is death” following their father’s fatal encounter with a drunk driver. While Bobby and Dannis moved on with music and family, the alcoholic David proved less resilient. His life began and ended with Death. Giving the group’s archive to Bobby, recently reissued by Drag City Records, he insisted “The world’s gonna come looking for it one day.” How right he was. And how sweet is his vindication. Brian Miller

PDirty Wars

Opens Fri., June 28 at SIFF Film Center. Not rated. 98 minutes.

Less a documentary than a meditation, Dirty Wars is a careful essay on what the War on Terror means in the Obama era. That’s not to disparage the journalism here, which is as daring as any you’ll see in a war documentary. Richard Rowley’s cameras follow Jeremy Scahill as he meets Somali warlords and travels Taliban-controlled Afghan roads to see firsthand the results of U.S. foreign policy. But the doc’s true brilliance comes when Scahill steps back from the impossibly muddled facts on the ground to ask “Where does it end?”

Dirty Wars begins in 2010 Afghanistan, at a dangerous outpost well outside the Green Zone. Scahill visits Gardez, where an American raid left a police commander and two pregnant women dead. The village leaders tell him the troops were part of what they call “the American Taliban” on account of the beards the men wear. From there, Scahill tries to understand how this American Taliban—officially the Joint Special Operations Command—figures in the War on Terror. His conclusion: While Obama is withdrawing troops from Iraq and Afghanistan, he’s simultaneously using the JSOC to wage war across the world, ordering strikes and raids in supposedly allied nations. Anyone who makes a legitimate threat against the U.S. (as determined by the U.S.) can become a potential target on the JSOC kill list. In this new war’s “twisted logic,” Scahill argues, even the teenage sons of Islamic radicals—children who might grow into terrorists—could be targeted.

Even those who’ve followed Obama’s honed and droned war closely will enjoy the clean cinematography and front-line journalism offered by Dirty Wars. The movie does suffer from a few too many cutaways to Scahill’s furrowed brow and baby-blue eyes. And it raises so many issues—the role of mercenary warlords in American campaigns, media complacency, the riddle of Gardez, etc.—that it would take a movie three times Dirty

Wars’ length to tie up all the loose ends. But at a moment when Edward Snowden is trying to escape espionage charges in Russia and Obama’s promise to reduce drone attacks rings hollow, the film perfectly captures the sinister undertone of all that hopeful White House rhetoric. Daniel Person

Evocateur: The Morton Downey Jr. Movie

runs Fri., June 28–Wed., July 3 at Grand Illusion. Not rated. 90 minutes.

Today it’s easy to hate on Bill O’Reilly, Glenn Beck, and Sean Hannity, but how many remember Morton Downey Jr.? The spiteful, short-lived cable phenomenon of the late ’80s also sprang from talk radio, and this tribute film posits him as their progenitor. Downey, the son of a now-forgotten singer, is a ludicrous Reagan-era footnote to the Tea Party boiling of today, but he ought to be an object of legitimate study. Unfortunately, this is a fan doc whose multiple directors (Seth Kramer, Daniel A. Miller, and Jeremy Newberger) haven’t got the brains to place Downey in any sort of context.

A failure as a ’50s crooner, a preppie pal of the Kennedys, Downey leapt into cable syndication by emulating ’60s TV host Joe Pyne (an even more obscure figure of the rabid right, unexplained here). If you lived in New York during the ’80s, as I did, Downey registered as a kind of WWF raconteur—he’d say anything for shock value, spit in the face of any guest (Ron Paul, Lyndon LaRouche, and Alan Dershowitz included), but never with any more conviction than a circus geek. Put the chicken in his mouth, and he would bite. He performed for a price, and there’s a kind of Brechtian pathos here that might be better explored in opera buffa or cabaret.

Chris Elliott made Downey a figure of fun on the Letterman show, but the parody was too mild. Here was an Irish Catholic who sneered at the steerage that followed his once-despised ancestors to the New World. He scoffed at gays, blacks, women, liberals, Muslims, and Jews. At the end of his life (1932–2001), he repented of smoking, but nothing more. And what of those he’d defamed and reviled? A good Catholic admits guilt—the absence of which, for Downey and Evocateur’s filmmakers, I can not absolve. Brian Miller

How to Make Money Selling Drugs

runs Fri., June 28–Thurs., July 4 at Northwest Film Forum. Not rated. 96 minutes.

One of my best friends is a reformed drug dealer, though he did not achieve the subsequent music-career success of 50 Cent, who’s interviewed in this initially promising advocacy doc. Using Grand Theft Auto graphics and editing, director Matthew Cooke starts satirically, as if he’s producing a how-to guide for the drug trade. Ex-dealers and ex-cops explain their methods, costs and distribution are discussed, and the film actually feels subversive for a while—like posting bomb-making instructions on the Internet.

Then the celebrities start creeping in: Susan Sarandon, Woody Harrelson, Eminem, Russell Simmons, and company. They already have money, and what they want is for us to legalize drugs, or at least end the war on drugs, which is certainly a legitimate argument. Still, this earnest discussion of the issues—including our nation’s shameful incarceration rate of African-Americans—is at odds with the snazzy packaging. Cooke means to entertain us with his cheerful rogues, pitchman narrator, and movie clips (cue Scarface), but his thesis needs a more sober presentation if it’s ever gong to be mainstreamed. Young people, baby boomers and below, are already on board with Cooke. Politicians and middle-of-the road voters are a different matter. To persuade them, as this film will never do, you need to hear from current cops and doctors about public safety and harm reduction. (This was the approach taken by the backers of our state’s Initiative 502, subject of the new documentary Evergreen, seen at SIFF and likely to return.)

In its latter chapters, How to Make Money covers a lot of ground: from our first ’30s drug laws to Rockefeller-era mandatory minimums to DARE and Len Bias and “Just Say No.” The tone becomes scattered among so many talking heads; and it’s telling that Cooke couldn’t get anyone from the federal government to participate. (We see Gil Kerlikowske, our former police chief, in a clip before he became Obama’s drug czar.) The film too often feels in need of Adderall to focus. It takes someone like David Simon, the ex-crime reporter and creator of The Wire, to provide a calm, succinct analysis of the underlying economics: In low-income neighborhoods, he says, the drug trade “is the only factory that is hiring.” Too bad Simon didn’t direct this movie. Brian Miller

The Painting

Opens Fri., June 28 at Varsity. Not rated. 78 minutes.

Suitable for older kids, Jean-Francois Laguionie’s animated French parable of class distinction takes place in a fairy-tale setting of castles, balls, and enchanted forests. There are three social castes: the colorful Alldunns, the Halfies, and the Sketchies, whose names correspond to their state of painterly completion. At the top of the pecking order, the smug Alldunns derive their authority from a divine Painter who’s departed the scene. Relegated to the garden are the imperfect Halfies (kind of like mulattos), while the sad, skeletal Sketchies are banished to the forest like savages. (“They should be tossed in the trash,” sniffs one castle dweller.) Naturally there’s a cross-class romance; there follows an Oz-like quest through the jungle, where giant, sentient Dr. Seuss-like flowers aid our heroes. (The dialogue’s dubbed into English, so the story’s easy to follow.) But where the film turns ingenious is the point our four fugitives reach the end of the known world—a membrane of canvas that divides them from the Painter’s studio.

What ensues is a clever twist on The Purple Rose of Cairo and Buster Keaton’s Sherlock, Jr. The main characters escape from one painting to the next, picking up new friends along the way and providing an art-history survey of early-20th-century styles. Post-Impressionism yields to early Cubism; there are allusions to Picasso and Modigliani; and the film’s flatly crayoned animation style even ventures into CG. (You could readily see the premise being adapted to Pixar.)

Still, The Painting ultimately runs thin on ideas, and the allegory’s a little too heavy for adult viewers. Must Ramo’s nose be so hugely Semitic? Must Lola be so conspicuously African-featured? The Sketchies become all-purpose signifiers for the oppressed: like Jews during the Holocaust, Bosnians during the ’90s, or starving immigrants seeking refuge in Fortress Europe today. The fairy tale becomes a bit too freighted, and some of the charm is lost. However, the French do love a good revolution, and when the Alldunns’ chromatic fascism is finally toppled, it’s not bombs but daubs of paint that create a fair new multihued society. Brian Miller

The Rambler

runs Fri., June 28–Thurs., July 4 at Northwest Film Forum. Not rated. 97 minutes.

Formerly based in Seattle, writer/director Calvin Reeder will be introducing his new trailer-trash picaresque, which is steeped in the horror flicks and road movies of the early ’70s. Dermot Mulroney plays the nameless, enigmatic drifter who leaves jail, quits his job at the pawn shop, and forsakes his meth-head buddies in the desert. Maybe there’s a job on his brother’s ranch in Oregon, maybe he’s on a spiritual quest, or maybe it doesn’t matter. The Rambler is being tracked by UFOs or drones high in the sky, unless they’re a figment of his imagination. He never removes his dark glasses. He smokes a lot. He plays a little guitar. He gets hustled into a hobo-fighting competition. Later he thumbs a ride with a mad scientist who keeps mummies in the back of his wagon. The scientist has a device, messily assembled from military surplus, “that records dreams to VHS.” What he doesn’t tell customers, however, is that it can also cause their heads to explode.

For Reeder, one senses, texture matters much more than story logic. This is a hallucinatory lost world of truck stops and dream girls, where Satanic rituals and apocalyptic visions abruptly pierce the dusty Americana. (You half-expect Charles Manson to show up.) With its Polaroid cameras, sun flares on the lens, and pay phones, The Rambler reaches back to a transitional time in American cinema, when Two Lane Blacktop, David Cronenberg shockers, and Roger Corman exploitation movies all played the same drive-in. The Rambler is like a feverish distillation of all those fixations. It’s not exactly a head-trip movie in the old LSD sense, but the Rambler himself is traveling between the zones of the real and the unreal. He could be a ghost, for all we know, or an Orpheus-like figure on an underworld quest. His motto: “My only true home is the highway.” He keeps moving, and The Rambler likewise refuses to settle into any polite, safe genre. Brian Miller

The Secret Disco Revolution

Opens Fri., June 28 at Varsity. Not rated. 84 minutes.

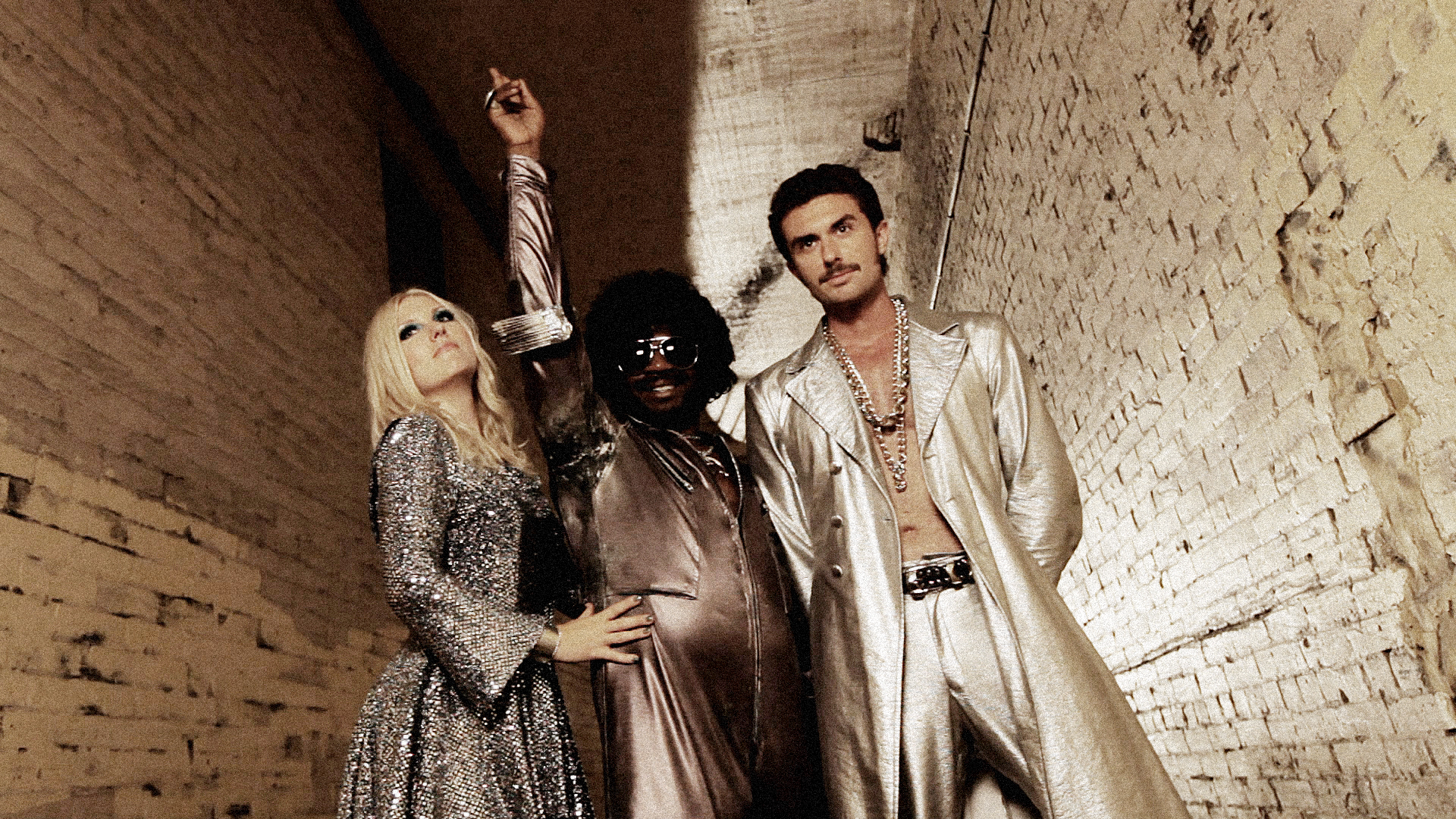

Do a little dance. Make a little love. Get down tonight. If you suspect that this nugget is not merely the chorus from a disco song but also philosophy to live by, you might be ready for The Secret Disco Revolution. This documentary attempts to place the glitter ball and “The Hustle” back in their proper cultural context. Or any cultural context. Director Jamie Kastner straps on his platform shoes and pukka-shell necklace and goes to bat for a much-maligned musical era, which, he argues, has more social significance than we give credit.

There was a secret agenda behind disco, Kastner suggests: The music was a Trojan horse for the advancement of gay rights, African-American artistry, and women’s sexuality. All of a sudden, “Right Back Where We Started From” might need another listen. Kastner plays it tongue-in-cheek. To balance the erudite academics on screen, he includes vignettes of three actors, costumed as the worst Mod Squad imitators ever, who wander around carrying a disco ball while a narrator describes—in hilariously sober tones—the plan to smuggle the gay/black/female revolution into America.

The musicians themselves, happily recalling disco’s daffy heyday for Kastner’s camera, were unaware of this revolution . . . or so they would like you to think. The engaging roster includes Gloria Gaynor, Thelma Houston, and Robert Kool Bell (of Kool & the Gang); they’re a fun group—and who knew one-hit wonder Maxine Nightingale was so right on? Only Harry Wayne Casey (that’s KC of KC and the Sunshine Band) comes off as a pompous ass—a disillusionment for those who cherish “(Shake Shake Shake) Shake Your Booty” and “I’m Your Boogie Man.”

Disco’s tawdrier hangover is described, too, with the usual attention paid to the nightly coke-snorting bacchanal at Studio 54 and the infamous Disco Demolition Night at Chicago’s Comiskey Field in 1979. Even then, the latter event—a crowd rioting in celebration after a box of disco records was detonated in the outfield—was written about as having racist and homophobic overtones.

The Village People have their own take on the meaning of it all: They are shocked, or at least annoyed, at Kastner’s suggestion that their songs are anything other than good-timey dance music for those who enjoy the YMCA, the Navy, or macho men. Gay subtext? They’ve never heard of such a thing.

My peers at Blanchet High School voted “Get Down Tonight” our class song, so I can hardly be objective. Whatever its flaws as a movie, or even as a history of disco (I must subtract points for the omission of George McCrae’s seminal “Rock Your Baby”), this film serves up the tangy atmosphere of a weird era—all to a maddening 4/4 beat. Robert Horton

20 Feet From Stardom

Opens Fri., June 28 at Guild 45th. Rated PG-13. 90 minutes.

Who dreams of being a backup singer? Our culture is made for the star, the frontman, the diva—with or without Auto-Tune. This might be why 20 Feet From Stardom, an otherwise delightful documentary, is tinged with an air of disappointment. Meeting the full-throated likes of Merry Clayton, Claudia Lennear, and Lisa Fischer, we understand these are masters of their craft. But the question nags: If they are masters, why aren’t they stars?

20 Feet engages that question, although somehow it’s a shame we have to ask it. Why wouldn’t it be enough to make a nice living, meet interesting people, and bring beautiful song into the world? If the soulful Fischer doesn’t have the killer instinct it takes to sacrifice everything for the spotlight, maybe she’s got it figured out. The film includes some who made the leap, including Darlene Love and Sheryl Crow, but the focus is mostly on the folks who’ve made a career out of being in the background. Like the 2002 doc Standing in the Shadows of Motown, it’s got a built-in hook: all that great music, served with annotations from musicians.

The stories are good, including accounts of the night Clayton joined the Rolling Stones to add her astonishing vocal to “Gimme Shelter,” a track that still stands as the backup vocalist’s brass ring: stealing a song from the lead. Mick Jagger, interviewed here, takes it all in stride. Other luminaries weigh in: Bruce Springsteen, Stevie Wonder, Sting. But there we go again, tracking the stars when this is about the foot soldiers. And it’s their show, delightfully so, even if director Morgan Neville doesn’t organize the material in a way that feels entirely intuitive. Despite the choppiness, the prime footage from George Harrison’s 1971 Concert for Bangladesh or Jonathan Demme’s 1984 Talking Heads concert doc Stop Making Sense is exciting.

It’s all about the blend of voices, as we hear when Love reunites with her former choir-mates for impromptu vocalizing. Well, not entirely the voices: Certainly Ike Turner had more in mind when he put the Ikettes in skimpy outfits behind his wife Tina, thus ensuring that future generations of backup singers would have to shimmy as well as sing. Nostalgia isn’t the only note. Judith Hill, who sang with Michael Jackson, must make decisions: If she accepts supporting jobs now, how will people think of her as a solo artist? It’s a long way from the Ikettes, but the stigma remains. Robert Horton

E

film@seattleweekly.com