Opening ThisWeek

About Time

Opens Fri., Nov. 1 at Thornton Place and other theaters. Rated R. 123 minutes.

If Woody Allen can leaven his comedies with supernatural gimmicks, why can’t Richard Curtis? The British author of Love Actually and Four Weddings and a Funeral has built his latest project around time travel, but Curtis isn’t interested in the vasty reaches of future worlds or anything like that. His focus remains romance, played out on a modest scale.

On his 21st birthday, Tim Lake (Domhnall Gleeson) is taken aside by his father (Bill Nighy) and informed of the family gift: The Lake men can time-trip. There are temporal restrictions, but basically Tim can go back and fix past errors by going into a dark closet and thinking hard about the previous moment in question. This is especially helpful during his courtship of Mary (Rachel McAdams), a cute and funny catch who seems to love him as much as he loves her. This is one of the odd notes about About Time: The central romance pretty much goes swimmingly. There aren’t that many bumps in the road, and Tim’s ability to go back and revise the past means he can wriggle out of most awkward situations. A couple of weird butterfly-effect incidents require extra effort, but the love story itself is smooth sailing, for a romantic comedy.

Curtis is as skillful with deft one-liners and a prone to mawkishness as ever. Toward the end of About Time, as though sensing the blandness of the central couple, he steers the film back toward father and son. This gives a nice opening to Nighy (when is this cagey pro going to get his first Oscar nomination?), but it makes way for beer-commercial sentimentality, too. McAdams fulfills the dream-girl outline with ease. (Curtis has realized you can’t write British dialogue for an American—or in this case, Canadian. I still feel bad for Andie MacDowell in Four Weddings, trying to make London syntax work with her flat Yankee accent.)

One of the movie’s pleasures—and it does have them—is the chance to watch an actor take his first leading-man shot. Gleeson, who was quite good in the otherwise misbegotten Anna Karenina, looks like a young Michael Caine but with half the aggression. His father is Brendan Gleeson, the burly Irish master, and he has his father’s red hair and sly humor, if not his authority. But this movie doesn’t cry out for authority—just wispy, winking charm. Robert Horton

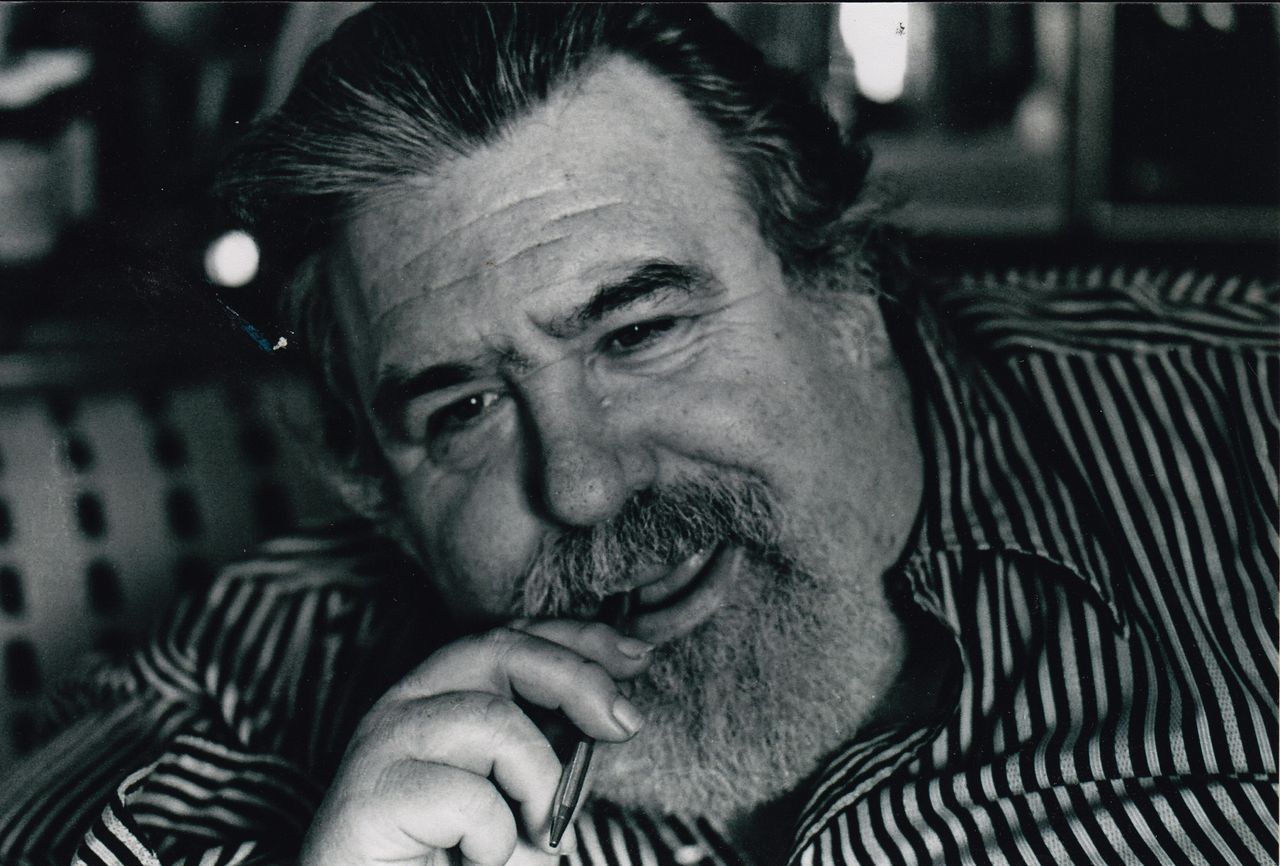

PAKA Doc Pomus

Runs Fri., Nov. 1–Thurs., Nov. 7 at Grand Illusion. Not rated. 98 minutes.

“You gotta live something in order to sing something.” Those words, spoken here by legendary soul singer Ben E. King, might be the blueprint for the blues, but they also serve as a lodestone for this doc about Jerome Felder, a disabled Brooklyn Jew who became one of the most influential songwriters of his generation.

His improbable story, captured in interviews, music, and archival clips and photos, is naturally transfixing. Stricken by polio at a young age, Felder fell in love with the blues after hearing Joe Turner sing on the radio. By the 1940s, he was sneaking into African-American blues clubs as a teenager, propped up on crutches, singing the blues that he lived. To keep his disapproving mother off the scent, Felder adopted the performance name Doc Pomus. It stuck through the next 50 years of writing and recording.

Filmmakers William Hechter and Peter Miller tell his story straight, weaving old interviews with Pomus (1925–1991) with remembrances from family, friends, and a handful of rock’s early architects. All this is spliced among entries from Pomus’ journal, mesmerizing in their lyrical beauty and given special poignance by being read by Pomus’ friend Lou Reed, who died this very week. About his early love of the blues, Pomus writes, “It wasn’t a monkey on my back; it was a midnight lady with a love-lock on my soul.” The filmmakers trace Pomus’ unlikely victories, pockmarked with fits of self-doubt and the humiliations of polio, on the way to fame and family. But this is no hagiography: Pomus is shown struggling with women, gambling, and food, which makes his blues all the more believable.

Besides the heartbreak and redemption is the jukebox full of great songs. We hear early tunes Pomus wrote for his childhood hero Turner, hits he authored for Ray Charles, and teeny-bopper classics penned with songwriting partner Mort Schuman. The doc’s rich soundtrack also includes “A Teenager in Love, ” a litany of Elvis songs (including “Viva Las Vegas”), and the radio hits Pomus wrote for King and the Drifters (“This Magic Moment,” “Save the Last Dance,” etc.). Each song has a unique Pomus story behind it, as his daughter, Sharyn Felder, will explain at the Saturday, Sunday, and Monday screenings. Mark Baumgarten

Big Joy: The Adventures

of James Broughton

Runs Fri., Nov. 1–Thurs., Nov. 7 at Northwest Film Forum. Not rated. 83 minutes.

“Follow your own weird.” “I believe in ecstasy for everyone.” “When in doubt, twirl.” These pearls of breathtaking insight and wit came from the pen of poet/filmmaker James Broughton, subject of Stephen Silha and Eric Slade’s doc. Born in Modesto, Calif., in 1913, Broughton came of age in the bohemian San Francisco newly liberated by the end of World War II. Time spent in England resulted in his avant-garde short The Pleasure Garden, acclaimed at Cannes; he returned to SF to find the Beats in full flower. From there he blithely rode every zeitgeisty wave, through the Summer of Love and into the years of Gay Lib, as an elder statesfaerie. Pioneer or opportunist? Prescient genius or one of the most adept coattail-riders in American cultural history? I suspect the latter, judging from his twee, nursery-rhyme-scented poems and dismayingly dated, emptily self-indulgent shorts (some of which will be screened Saturday and Sunday at 5 p.m.). Despite his prolificacy, the clips shown in Big Joy suggest that he’ll be remembered in cinema history primarily as the father of Pauline Kael’s daughter.

Broughton married costume designer Suzanna Hart in 1962 but left her for poet Joel Singer in 1975 after three days of sex in a hotel room in Pennsylvania, an epiphany for him but an embittering blow to Hart—curiously strong reactions both, since Broughton had already had flings with both genders for decades. From then to his death in 1999 (in Port Townsend!), his work seems to consist of little else but talking about those three days. Affectionately researched and crafted, Big Joy’s sole but serious flaw is that it doesn’t make the case that its subject merits the attention. Gavin Borchert

Last Vegas

Opens Fri., Nov. 1 at Sundance and other theaters. Rated PG-13. 104 minutes.

The four actors assembled for the old boys’ night out that is Last Vegas all have Oscars on their shelves. This movie will not win any of those. Still, it is a measure of their skill that they do not betray a hint of embarrassment or condescension in the course of this lightweight bash. Perhaps they sense the shrewdness behind the project, which combines Hangover-lite hijinks with last-go-round mellowness.

They’re the Flatbush Four, buddies-for-life who gather in Sin City for the marriage of the slickest and most successful of them, Billy (Michael Douglas—who else?). In a spasm of feeling his mortality, Billy has proposed to his 31-year-old girlfriend, and the occasion puts the chums in a variety of moods. Archie (Morgan Freeman) wants to flee the safety of elderly life; Paddy (Robert De Niro) still grieves over his late wife, who chose him over Billy a lifetime ago; Sam (Kevin Kline) has a free weekend pass from his wife to get as crazy as he wants, as long as it snaps him out of his funk. Does Kline seem the odd man out there, somehow an actor of a different generation? He did lag behind the others in making a big-screen first impression, although he’s only three years younger than Douglas. He certainly seems younger in Last Vegas, executing funny walks and finding fresh ways of delivering his lines. The others are cast so on-the-nose—De Niro grouchy, Douglas cocky—you can be forgiven for wondering what might’ve happened if they’d switched roles around.

Another Oscar-winner lurks in the cast: Mary Steenburgen, as a lounge chantoozie named Diana, an age-appropriate partner for whichever of the guys can move quickest. It’s nice to see Steenburgen get more lines than usual, and sobering to think of how long she’s been around without the opportunities of her male colleagues.

Things in Vegas go as you’d expect. The old-age jokes are doled out in different degrees of groan-worthiness, with asides about how rude these young kids are today, but hey—if we set an example, they might learn something. Director Jon Turteltaub (National Treasure) is an old hand at finding the comic beats in this kind of package, and the film moves along so smoothly it’s almost alarming. Nothing breaks the surface, and no moment gets close to the authentically restless elderly angst of Martin Brest’s Going in Style, a forgotten 1979 George Burns vehicle. Last Vegas is just one more trip down the bucket list. Robert Horton

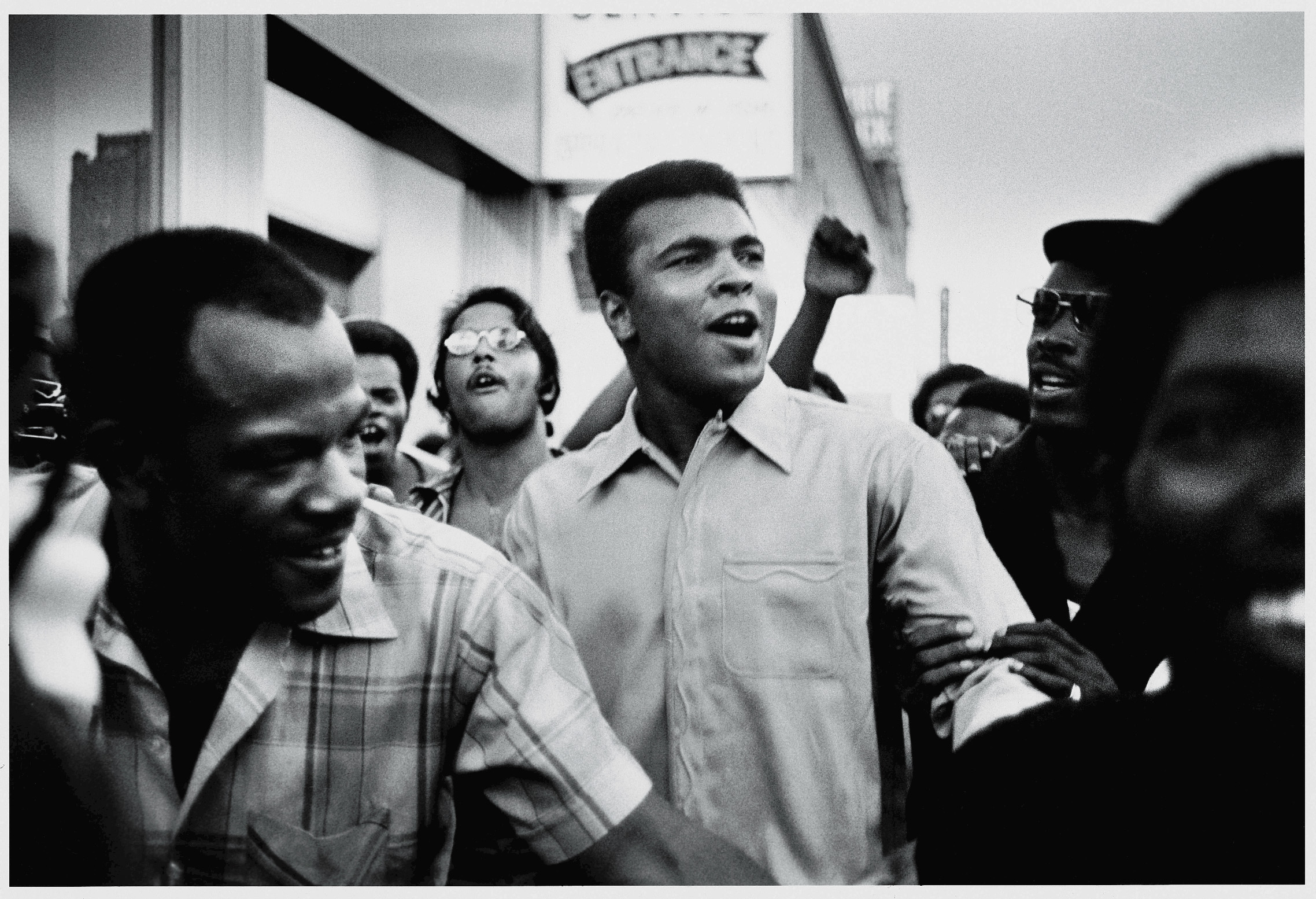

The Trials of Muhammad Ali

Runs Fri., Nov. 1–Thurs., Nov. 7 at Varsity. Not rated. 94 minutes.

The most famous athlete of the 20th century, his every fight and utterance covered by international media from 1960–81 (his boxing career), Muhammad Ali has left a mountain of archives for authors and filmmakers to mine. But here’s the catch: They’d better find something new to say after so many prior books and documentaries. Bill Siegel succeeds in pulling up only a few nuggets here, like Ali performing in the Broadway musical Buck White during his ban from boxing. That period, 1967–71, should’ve been framed to much tighter and more dramatic effect, yet Siegel falls into the trap of giving us the whole of the GOAT, which cannot be done in 94 minutes. (A Ken Burns series, maybe.)

I doubt many millennials watch boxing today, and for some this footage may be fresh. The sport is in such decline, its brain-injury stats so damning, that the tale of Ali’s conscientious-objector lawsuit—to avoid being drafted into the Army during the Vietnam War—feels as distant as the Civil War. Siegel punches it up with some fresh interviews, but his sources are too fawning (especially Louis Farrakhan, that smiling clown from the Nation of Islam). Ali is great enough without being lionized yet again. His famously repeated quote “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Vietcong” is certainly true and courageous, but Siegel never digs deeper into Ali’s resentment about his loss of vocation—the millions he couldn’t earn while serving safely in a National Guard unit, far from the front lines. Brian Miller

P12 Years a Slave

Opens Fri., Nov. 1 at Guild 45th and other theaters. Rated R. 133 minutes.

How do you tell the story of something as enormous and horrifying as American slavery? In the case of 12 Years a Slave, the subject is played out on human bodies and in objects: a single sheet of precious foolscap writing paper, the juice of berries, a violin. Instead of taking on the history of the “peculiar institution,” the film narrows to a single story and these scattered things. It is based on a memoir by Solomon Northup, a free man from Saratoga, New York, who was kidnapped and sold into slavery in 1841. He is played by English actor Chiwetel Ejiofor (Inside Man, Dirty Pretty Things), whose Spencer Tracy–like ability to observe and calmly draw us into an experience is quite powerful here.

Solomon—robbed even of his name, he’s called Platt by his captors—passes through the possession of a series of Southern plantation owners. One sensitive slave owner (Benedict Cumberbatch) gives Solomon—a musician by trade—a fiddle, adding the sincere hope that his family may hear Solomon play for many years to come. (That sort of clueless “kindness” is one of the film’s rich veins of horror.) A more physical sort of gash is delivered in flesh-rending ferocity by the cruel cotton farmer Edwin Epps (Michael Fassbender), whose attention also gravitates toward the furiously hard-working Patsey (Lupita Nyong’o).

Patsey, like Solomon, is caught inside the terror of not knowing how to play this hand. Do they keep their heads down and try to survive, or do they resist? The prospect of Patsey becoming her owner’s mistress is suggested in a fascinating scene featuring the great Alfre Woodard. We don’t get to know many enslaved characters, because the perspective, and the confusion, belongs to Solomon. This is no Amistad or Schindler’s List, tackling the big story, but a personal tale (if you’re curious about what happens to supporting characters, forget it). British director Steve McQueen, who developed the film with screenwriter John Ridley, made the fascinating Hunger and the literal-minded Shame, and there’s something deadpan, almost blank, about the way he portrays the fear and malice of this situation. This is effective, even if might occasionally make you wish for the emotion and formal design of a Spielberg.

The film’s and-then-this-happened quality is appropriate for a memoir written in the stunned aftermath of a nightmare. As we get to the end, with slivers of hope and disappointment, the result is effective indeed. (I wish a gnarlier actor had played the small but key role taken by Brad Pitt, one of 12 Years’ producers, but it doesn’t kill the moment.) Along the way McQueen includes idyllic nature shots of Louisiana, as though to contrast that unspoiled world with what men have done in it. The contrast is lacerating. Robert Horton

Una Noche

Runs Fri., Nov. 1–Thurs., Nov. 7 at Sundance Cinemas. Not rated. 90 minutes.

There are wrenching changes going on in Cuba, as we know. The system of two currencies—one for tourists—is being abandoned. With the Cold War over, former allies like Russia aren’t willing to support the island nation. And though the retired Fidel Castro isn’t dead yet, the old regime is starting to crack. For that reason, while fairly obvious, Lucy Mulloy’s debut feature carries a poignant impact. It follows three teenagers trying to escape the island on a raft to travel the 90 miles to Miami; we know this is a bad plan, and the past-tense narration of Lila (Anailin de la Rua de la Torre) adds to our sense of foreboding.

It takes an hour for Lila, her brother Elio (Javier Nunez Florian), and his pal Raul (Dariel Arrechaga) to push off from shore, during which time Una Noche gathers an almost documentary weight. Mulloy, a graduate of Oxford and NYU, brought a small crew to Havana to shoot the movie; and all her performers are local. They move through the streets with ease—grabbing onto buses while coasting their bikes; diving off the pier into turquoise waters; stealing supplies and fleeing the cops. The film was clearly filmed with government permission (undoubtedly for a fee), but the script is quite frank about Cuba’s problems. Raul’s mother is a prostitute with AIDS. The police beat anyone who dares approach the tourists. The skyline of Havana itself is frozen in a crumbling, 50-year-old stasis. It’s a scenic ruin ringed with pristine beaches and palm trees; no wonder visitors come to stay in the gated beachside resorts.

But eventually we have to climb onto the raft and face the swirling sharks (not unlike All Is Lost). There, Lila is the sole realist about the situation. If they get to Miami, she says, they’ll just end up slaving in a hot kitchen. But there’s a terrible and oppressive sense in Una Noche that if they stay in Cuba, their fate will be exactly the same. Brian Miller

PViola

Runs Fri., Nov. 1–Thurs., Nov. 7 at Northwest Film Forum. Not rated. 65 minutes.

My vote for most delightful movie ending of the year goes to Matias Pineiro’s Viola, the latest from this spirited young Argentinian director. Even if the film’s unfolding is sometimes puzzling, by the time we reach the tuneful conclusion, sheer charm has won the day. Not that it takes long to reach the end. Viola runs just 65 minutes, as though it leaves out the explanatory material that might make its world more accessible. Basically, we meet a group of Buenos Aires young people, many of whom are actors working on a Shakespeare production that includes pieces from different plays. The show has an all-female cast, and the film itself is much more interested in its women than its men. One character, Viola (Maria Villar, a wonderful straight-faced presence), runs a DVD-pirating service with her boyfriend and delivers her goods by bicycle around the city. The casual storyline comes close to bringing together its different elements when Viola finds herself in a car with two of the actresses from the stage play. This conversation is surreal for a few reasons, but as they go along talking about the possibility that the humble bike messenger might actually star in the play they’re working on, you might begin to wish that life really worked like this.

Pineiro was 30 when he made the film, and it’s already his fourth feature—if you count the 43-minute 2011 film Rosalinda, which also put Shakespeare rehearsals at the center of a mixed-up plot. His use of literary quotations and elliptical storytelling suggest that he doesn’t go along with old-fangled notions of serving up narrative, yet he manages to bring together his threads in oddly satisfying ways. (That’s where the delightful ending comes in.) Even when his movies are hard to track, something about them conjures a youthful breezy, try-anything energy. It isn’t just larking about—it’s more a sense that the old methods aren’t working, so let’s try something else. This creative underclass of young Argentinians might exist only in Pineiro’s imagination, but that’s not a bad place to be. Robert Horton

E

film@seattleweekly.com