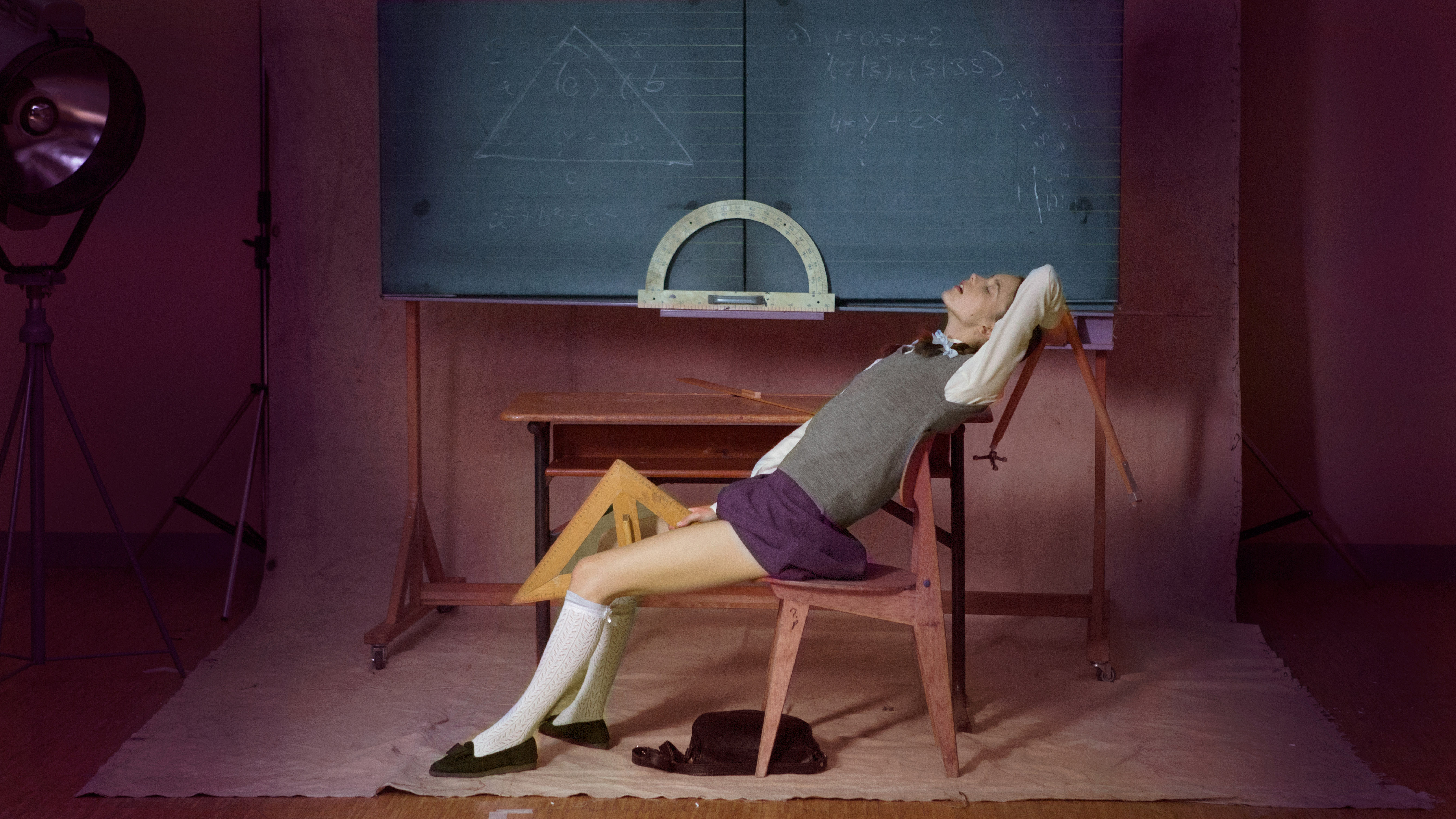

Nymphomaniac: Vol. I

Opens Fri., March 21 at Harvard Exit. Not rated. 110 minutes.

Lars von Trier’s biggest trick has been convincing the world he is not serious. The Danish filmmaker adopts such a puckish public demeanor, and is given to such willful outrageousness (whimsically comparing himself to Hitler at a Cannes press conference was a particular lulu), that he has turned himself into a brand-name oddball just this side of David Lynch. Superficially, his movies create the same kind of taboo-breaking impression: radical looks at sexuality, politics, and violence (Breaking the Waves and Antichrist among them), culminating in a remarkable portrait of depression and the end of the world (Melancholia). By titling his new project Nymphomaniac, and letting it be known that this four-hour, two-part picture includes marquee names and unsimulated sex, von Trier is acting up again. There goes that old devil Lars, fanning the flames as always.

And then Nymphomaniac: Vol. I begins. Within a few minutes, there is little doubt about the filmmaker’s seriousness. Not that the film is without a playful side; droll Danish humor is abundant. But this is a real journey, recounted to us by a woman named Joe (Charlotte Gainsbourg), who is discovered, beaten up, in an alley. Her rescuer, Seligman (Stellan Skarsgård), listens intently to her account of a life in thrall to sex, but he also interjects his own spin on things; to his mind, Joe’s stories can be seen through a variety of fishing metaphors. She is no mere slave to her libido, however—this story is about how Joe frames sexuality, uses it (to borrow a phrase from Pat Benatar) like a weapon, studies it, or succumbs to it. Her parents (Christian Slater and Connie Nielsen in flashback) are in the mix, as is the rough-edged fellow (Shia LaBeouf) who keeps appearing in her life. Stacy Martin plays Joe as a young woman, in an impressive film debut. The bits of explicit sex are handled by unnamed body doubles, or prosthetic devices, or . . . well, let’s leave some things to the magic of the movies.

The biggest problem with Vol. I is that it is clearly only part of a bigger film. The end note is well-chosen and creates an emotional cliffhanger, but we’re just halfway there. Thus it’s hard to say whether von Trier has solved Joe’s story—and Seligman’s curious place in it—because there’s no resolution at all. Joe describes herself as a sinner, but is von Trier really going to take that at face value? Tune in for the next exciting chapter, opening hereabouts on April 4.

film@seattleweekly.com