Night Across the Street

Runs Fri., April 26–Thurs., May 2 at Northwest Film Forum. Not rated. 110 Minutes.

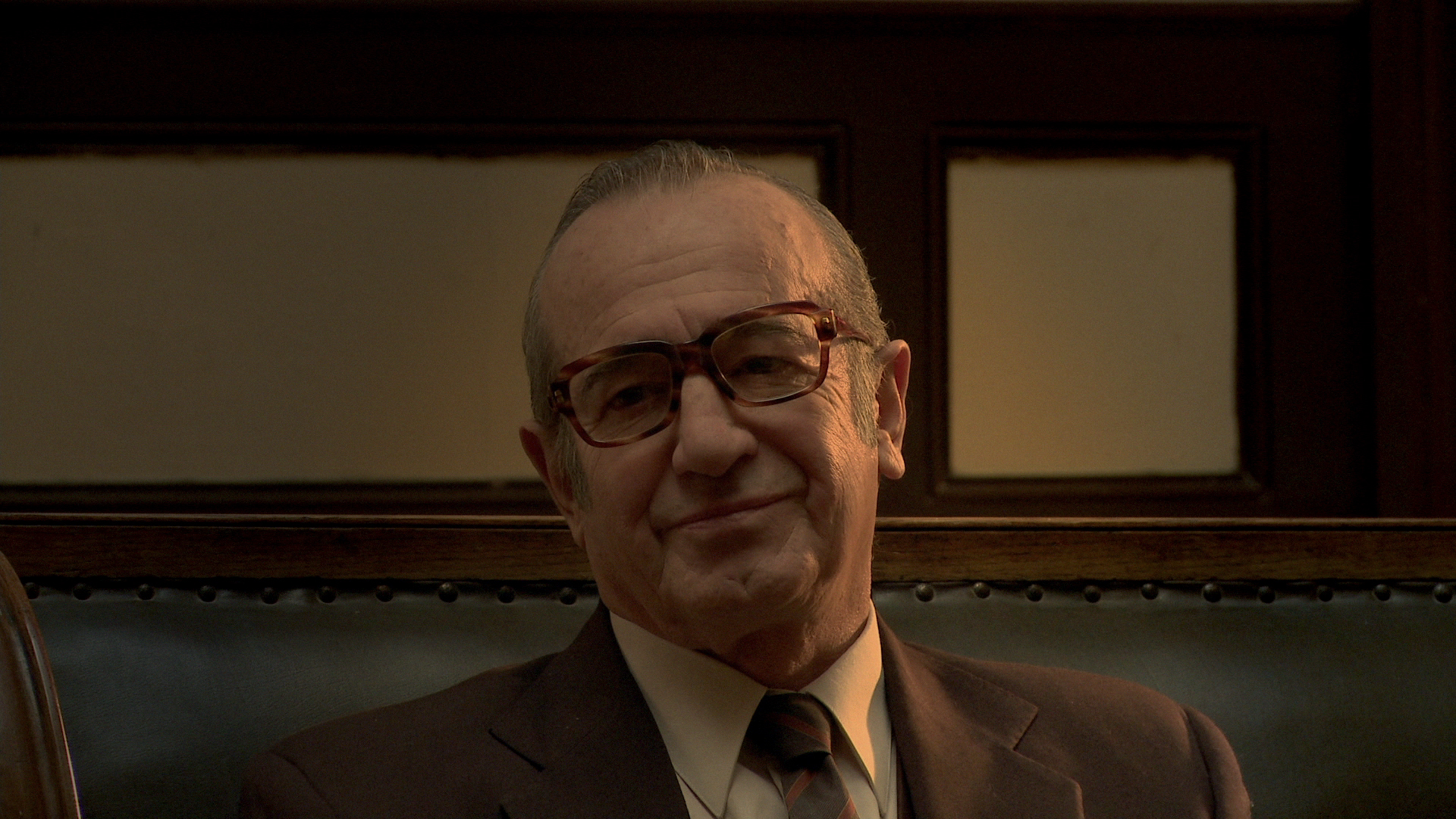

Billed as the last completed film by Raul Ruiz (1941–2011), the prolific Chilean expat who worked most of his career in France, Night Across the Street also bears the stamp of Chilean writer Hernan del Solar, who’s even less known in the U.S. In this adaptation of Solar’s stories, Celso (Sergio Hernandez) is nearing retirement, an office clerk with no wife or kids. His mind drifts back to childhood scenes in which he’s sometimes a youthful participant, sometimes a grown observer, sometimes both. In the present—though temporal lines are extremely fluid—he lives in an old boardinghouse among various colorful characters. It’s a place of memories and fantasy figures; its rooms are like the chambers of Celso’s own mind, with doors leading to doors of remembrance.

Old Celso’s best friend is imaginary: the Chilean writer Jean Giono, a real figure here incorporated into the fiction. He and Celso discuss “marbles of time”—how we don’t experience time as a continuous flow, which is very much Ruiz’s working method here. Old Celso is also called “an immobile voyager,” a man sailing through time from his armchair. All his alarm clocks and ships-in-bottles are tokens of time suspended (or possibly repeating itself). In scenes from his ’50s youth, Beethoven shows up, striding across the soccer field. Young Celso (Santiago Figueroa) and a pal even take the composer to the movies, where the cowboys and Indians confound poor Beethoven. (“How tall the people are!”) There are also periodic consultations with Long John Silver, his pirate vessel seen crashing across the celluloid waves of old black-and-white Hollywood. (Ruiz not-so-coincidentally directed a version of Treasure Island in 1985.)

The tone is by turns whimsical and absurd, comic and morbid, slow and silly. Scenes suddenly shift in visual and metaphysical perspective. You can see the influence of Borges and Bunuel; there’s a further Pirandello aspect to the boardinghouse characters, so self-aware of their place in this fictional world. Old Celso claims to be waiting for an assassin, but even a bloody shootout doesn’t put an end to Night. The victims, now ghosts, hold a cheerful seance—but who are they trying to contact? Usually it’s the living who seek the dead. But for Ruiz, those realms are parallel or even circular, rolling around like marbles.

bmiller@seattleweekly.com