Melinda Bargreen’s new history of Seattle Opera is about as good as such institution-published, self-congratulatory commemorations can be. Lots of people will refer to 50 Years of Seattle Opera (Marquand Books, $65) to settle arguments and joggle memories. It will appear on Northwest coffee tables indefinitely, until decorators insist on something more up-to-date.

No one will read it for pleasure. That’s to be expected: A careful traversal of more than 200 stagings—each accorded its sentence or two of description, raves, faint praise, and all—isn’t meant for the nightstand.

I hope people who purchase it out of duty or nostalgia do try to read it, though. Bargreen’s coverage of the prehistory of opera in the Northwest sticks—starting in 1876—makes it clear that the legend of Seattle Opera as the bumptious natural child of the 1962 World’s Fair and a yokel with a flair for promotion was a media fabrication from the git-go.

But—from the standpoint of this Seattle Opera-goer from the mid-’60s onward—there was a kernel of truth to the tale that served the young company so well. It attracted first the patronizing attentions of the national and then the world media. And that myth depended on one man: Glynn Ross (1914–2005), born a Nebraska farm boy, but—by the time he reached Seattle—one who was as deep in the bag as any American of his age and time.

After fighting and being wounded in WWII, Ross had by ’63 also presented lyric theater to the troops in postwar Italy, saturated himself in Wagner’s Bayreuth during its golden postwar seasons under the composer’s grandsons, and labored for decades in the undergrowth of an art form defined and dominated by the nation-spanning Texaco broadcasts from the Metropolitan Opera. Reading Bargreen’s copious account of Ross’ career between 1948 and 1963, you realize it was ideal for the making of an impresario. (A longtime Times critic, Bargreen also wrote his obituary for that paper.)

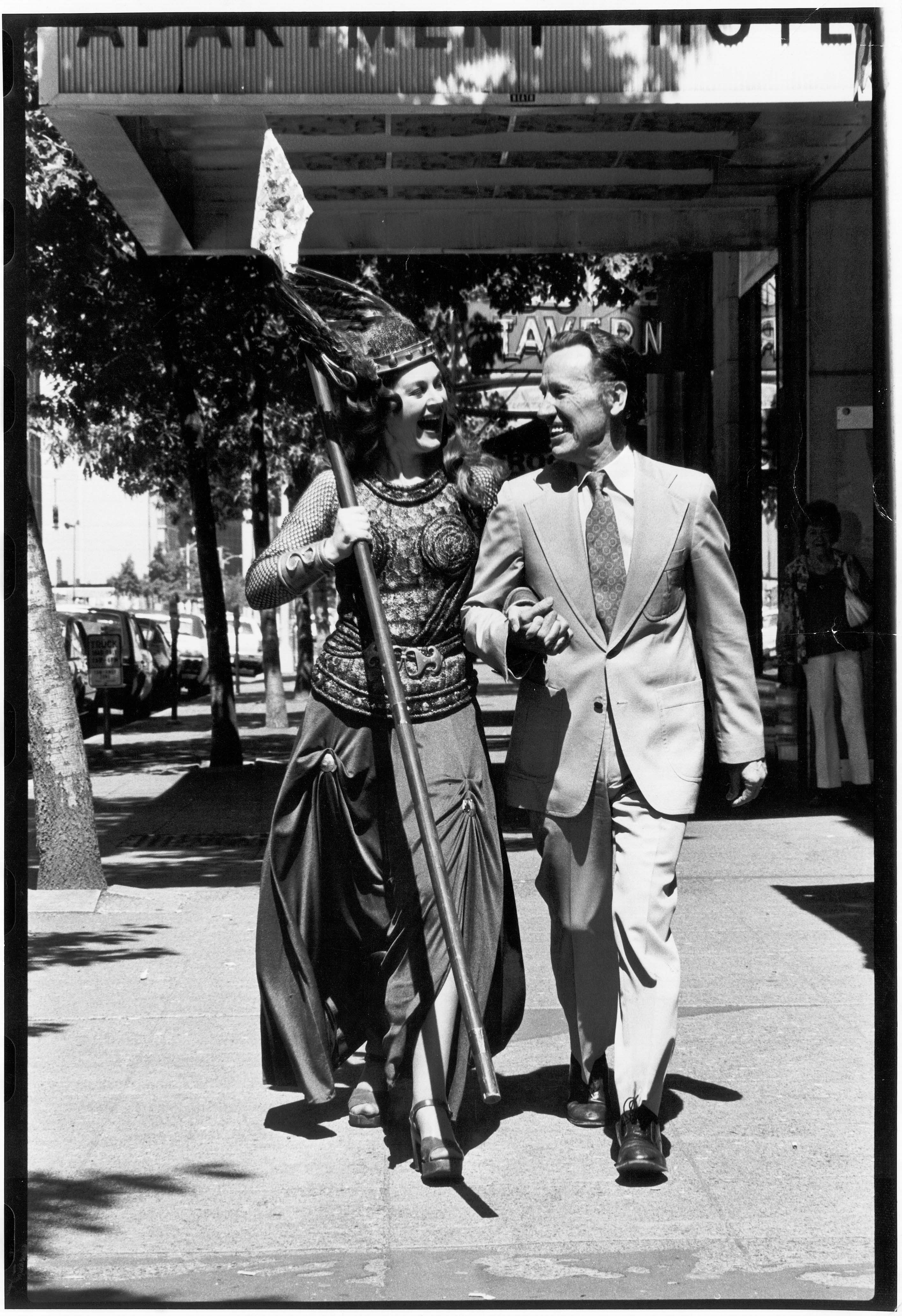

What doesn’t come across in Bargreen’s account—what couldn’t, in an official history/tribute like this—is what an extraordinarily strange man Glynn Ross was. Her straightforward rendering of his ultra-populist manipulation of the local media—the bumper-sticker reading “Get Ahead With Salome,” the “Mix It Up With Seattle Opera” painted on the drum of a cement truck—captures the jokey but effective side of his campaign to make opera a household word here, but misses the frenetic side of Ross the promoter. Only the chapter heading “Glynn Ross: Driven Dynamo” hints at the demonic side of Ross, the ferocious force he radiated, disturbing many observers even as they acknowledged his accomplishments.

Ross’ lack of formal education may have exacerbated his contempt of the formal airs and graces that accompanied operatic art in his day. He often asserted that anyone who couldn’t in a pinch mount a repertory item like Carmen or La boheme in 48 hours had no business in the opera business; and, during his 20-year tenure, productions routinely looked as if they had been thrown together in less.

A typical early Ross production had a star—a genuine star, preferably direct from the Met—as its tentpole, with everything else, including musical preparation, as an afterthought. And since the intended audience had prepared, if at all, for the experience by watching The Ed Sullivan Show, the formula worked pretty well.

That it worked at all must be attributed to one man: Henry Holt, the conductor and musical jack-of-all-trades who faithfully played straight man to Ross’ Zero Mostel from 1966-83. Holt’s significance has always routinely been underemphasized in Seattle Opera retrospectives, and Bargreen’s take is no exception; though he does get one little sidebar all to himself (as do stage managers, PR people, and secretaries).

Holt was fondly known to vocalists as “the singer’s friend” for his role as the one reliable element in a chaotic production environment. Orchestra members didn’t appreciate his laser-like focus on the stage, but came to respect his utter professionalism as Seattle Opera embarked on its date with destiny: its first staging of Wagner’s complete Ring of the Nibelung in 1975.

Ross paid tribute to Holt on his death in 1997, 14 years after their collaboration ended. But Holt’s most essential qualities for Ross were surely those he demanded of everyone who worked with him: absolute subordination, unquestioning loyalty.

My direct contact with Ross was rare in the early years; the media I then worked for swung enough weight to demand attention, but not enough to matter much. That changed in 1976, when the just-born Weekly unwisely chose to put me (as a battered Siegfried) on its cover and billed my Ring review as “Wagner 4; Downey 0.” Every time I visited the Seattle Opera offices for an interview after that, I felt like I was at the court of one of the less-bloodthirsty Roman emperors, with everyone metaphorically tiptoeing around the seat of power.

A scene from last year’s Ring production of Gotterdammerung, a Seattle Opera tradition begun by Ross. Photo by Alan Alabastro

That ’76 Ring review was symptomatic of a shift in public attitude to the opera’s many production shortcomings: from affectionate tolerance to sometimes cranky irritation. But it was Ross’ increasingly imperial worldview that led at last to the end of his phenomenal smile-and-a-shoeshine tenure as a one-man production machine. The late ’70s/early ’80s collapse of his pipe dream of a Wagnerian Valhalla on Weyerhaeuser-donated land in Federal Way—which Bargreen treats in a few embarrassed paragraphs—shifted power to a faction of the board that felt that the unaccountable Ross was an unsuitable figurehead for a grown-up opera company.

Thus ended Ross’ two-decade rule. His Esau-the-hairy-man was replaced by the smoothly patrician Isaac of Speight Jenkins, now retired more gracefully after a 31-year reign. For the company, it was a brilliantly right move. For Ross, it was a fall like Alberich’s in his beloved Ring: from king of the world to exile in Arizona, where he built a new, if diminished, opera empire. But the spotlight had passed.

Ross remains vivid in my memory, though. My last encounter with him was suitably strange. I was just off the plane at Phoenix’s Sky Harbor in 1995. It was about 4:30 in the morning, the hour dictated by a date with the bus to Grand Canyon and a few days’ hiking. While still coping with my tent and backpack, I was approached through the pre-dawn murk and the deserted tarmac by a diminutive figure with the unforgettably huge head and feral grin, unaccountably solitary and suited, but ready to take advantage of a rare opportunity. “Roger Downey,” he grated out, taking me firmly by the arm. “Roger Downey,” he repeated, pounding his other fist onto my other arm, as hard as an 80-year-old man has any business hitting anyone. And he kept assaulting me and repeating my name until I managed to remove myself from his iron grip.

I was shaken, I admit, but more by the ineffable weirdness than the physical attack. After a while, I saw the incident from his point of view. How many impresarii, offered his opportunity, would have lost the chance to deal decisively, if decorously, with a loathed enemy? Not Glynn. He was a scrapper to his core, and I miss that about the guy—and in this otherwise exemplary chronicle of the feisty company he founded.

books@seattleweekly.com