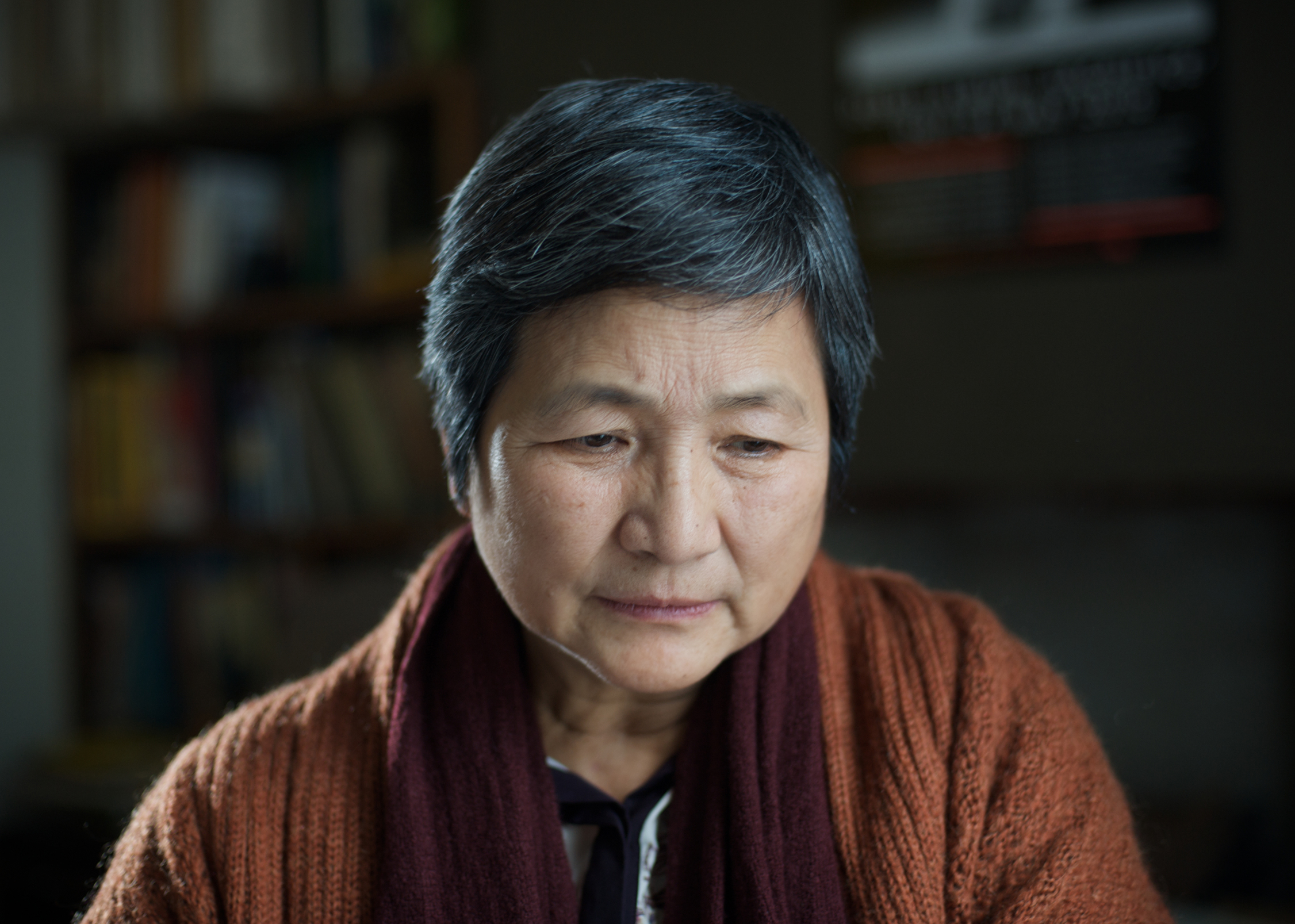

Marriage equality may be a new thing, but there’s always been equality in grief. The death of a lover is like the death of a spouse, though for Richard—whose partner was closeted to his conservative mother—that grief daren’t be spoken directly. In flashbacks and regular nursing-home visits to the widowed, Mandarin-speaking Junn (Cheng Pei-pei), who’s never adjusted to England or learned the language, Richard has to balance sadness and candor. Junn is now totally alone, harboring happy memories of Kai (Andrew Leung), living in a dreamy sort of reverie where Kai is as alive (though different) as in Richard’s own fond recollection. (The latter is played by Ben Whishaw, from Bright Star and Perfume.)

This kind of past/present dreamworld would be a challenge for any filmmaker, and I won’t pretend that writer/director Hong Khaou’s first feature carries off the spell in an unbroken fashion. Wisely, he punctuates the gauzy recollections with two tart elements set squarely in the present, providing some welcome humor. Visiting Junn, Richard brings the no-nonsense Vann (Naomi Christie) as his translator. Junn mistakes her for Richard’s girlfriend—convenient for him—and she also uses Vann’s services when a kindly widower (Peter Bowles) courts her at the old folks’ home. A series of awkward, tender, funny three-way conversations results, with Richard constantly reconsidering his words to Junn, interjecting to Vann, “Don’t say that.”

As Richard finds himself acting as a kind of surrogate son to Junn, almost channeling Kai’s ghost to her, the question arises as to whether loving someone and simultaneously lying to them is so wrong. This was essentially Kai’s dilemma with his mother, now perpetuated with Richard. Lilting is very much a memory play, Tennessee Williams in a different key, echoing Hong’s hybrid background. (His ethnically Chinese family emigrated from Cambodia to England in the ’80s, when he was a child; he’s lived a life of cultural translation.) Whishaw’s tremulous grieving may suggest a full-on weepie here, but Cheng’s dry-eyed performance helps contain such sentimental excess in Lilting. Though Richard and Junn have a loss in common, this poignant movie doesn’t insist that their different memories need to be reconciled. Opens Fri., Oct. 17 at Varsity. Not rated. 91 minutes.

bmiller@seattleweekly.com