“One of the things that is always important to me when I’m telling stories is truthfulness,” Malika Oyetimein tells me as we sit in a theater rehearsal space at the University of Washington. A burgeoning director in the Seattle theater scene, she’s made a big mark on the city in a relatively short time. Originally from Philadelphia, she moved to Seattle three years ago to get her MFA in directing at the UW. Shortly after, she directed Bootycandy for the Intiman Theatre’s summer festival and quickly found herself featured on City Arts’ 2016 Future List. Part of her success might be attributed to the dynamic lens she views her directing through—the lens of an activist. It’s a fusion she calls “artivism.” Through theater, Oyetimein strives to engage with a community in a way rooted in love and focused on social change, and her success is proving that the community is engaging back.

“If I’m not doing my art for community, I’m not sure why I’m doing it,” she says. Oyetimein’s brand of community building is politically poignant, intimate, and collaborative, and centers the narratives and experiences of black folks in America. One recent example is her production of Fucking A. Suzan-Lori Parks’ bluntly titled epic destabilizes “our ideas of mass incarceration, misogyny, patriarchy, [and] the role of women’s bodies in America,” as Oyetimein describes it. Coincidentally, the production opened one week after Donald Trump was elected. Fucking A takes aim at all these issues while also confronting the systemic and structural oppression that upholds them. Oyetimein will be defending her direction of the piece as part of her Master’s program.

She tackles shows like these in hopes of provoking a unique audience response. “I want people to leave with their assumptions shattered,” she says. “I want their stereotypes to be shattered, I want them to have to call their family members for clarification.” For Oyetimein, the theater is a place to rethink and readdress assumptions, to critically engage, and to leave changed. Fucking A was no exception to this vision.

Oyetimein’s values as a director deeply influenced her most recent work: Kirsten Greenidge’s Milk Like Sugar, which opened this past weekend at ArtsWest. One of her ideas is to “highlight the three-dimensionality of black girls growing up in the inner city. When I think about Milk Like Sugar, I think about how few stories … are centered around black and Latino girls that are written by black women. And so my vision for the show was to center, to fully articulate, what that would look like.”

The play follows the story of 16-year-old Annie and her friends. Annie’s youthfulness is ever-present, her desires shaped and tweaked by the people she loves. Oyetimein’s direction explores “what it feels like to be 16 years old and get information from disparate sources.” Friends, parents, partners—Annie and her friends struggle to parse these streams when it comes to making big decisions and surviving in the city. Oyetimein’s work looks to highlight the expectations and adversarial difficulties the girls face.

The production’s multifaceted design is central to supporting and maintaining the girls’ emotional journey. One important tool used to emphasize Annie’s emotional roller coaster is sound, crafted by sound designer Stephon Dorsey. “The sonic landscape of Milk Like Sugar is very intricate,” Oyetimein says. “We’ve created this musical landscape that [Annie] transverses, and it really tells a story, and hopefully a powerful one.” That landscape is youthful and dynamic; the actors dance with the music between scene transitions, expressing with their bodies the nuances of emotion they feel both alone and in a group. Oyetimein’s emphasis on collaboration is present in the interweaving of Greenidge’s original text and Dorsey’s design; the production speaks to her attentiveness to cultivating trust-based teamwork among the production team.

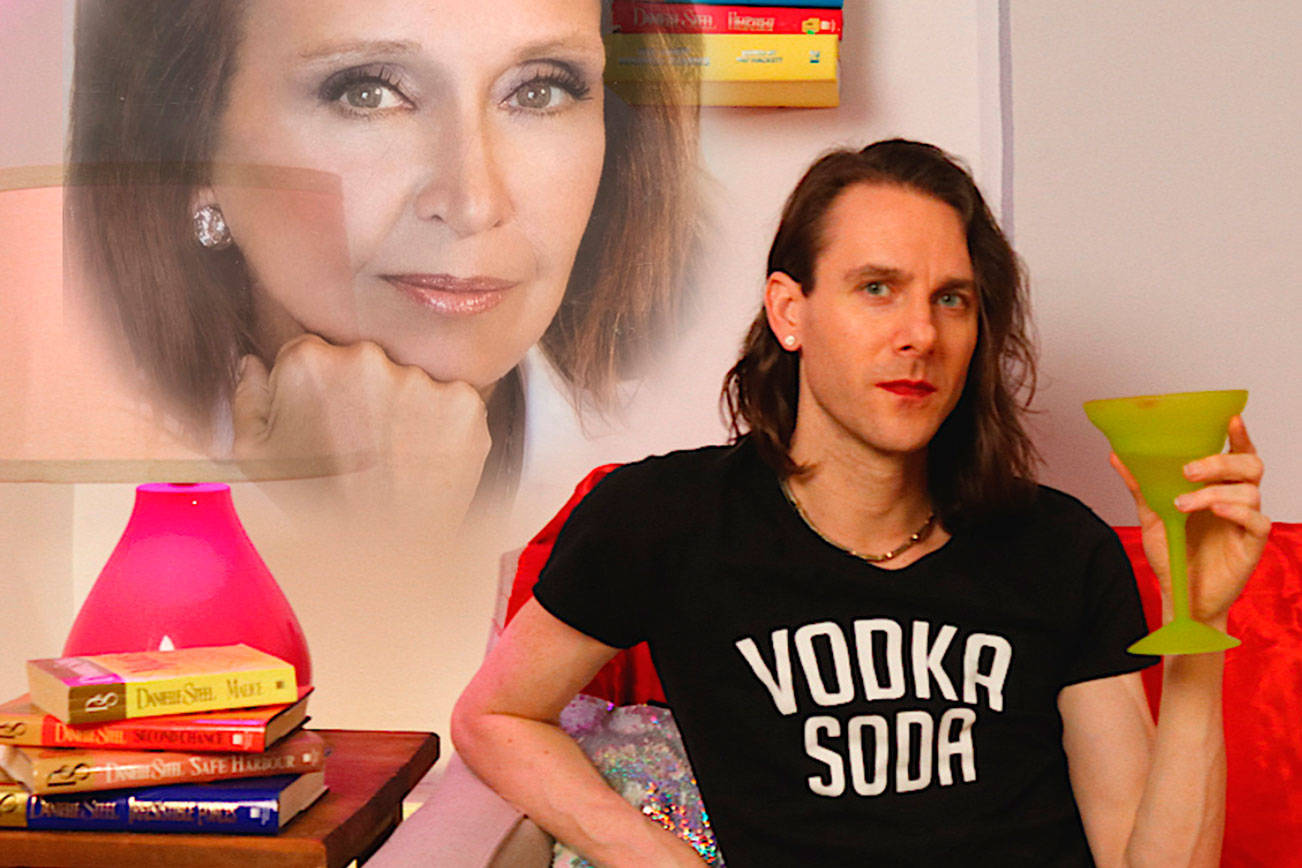

A mural visually supports this sonic ocean: “We’re telling the story with the face of a black woman ever-present,” Oyetimein says. She knew from the beginning this element of the production was vital, an allusion to the breathtakingly beautiful murals seen in Camden, N.J. (where the play is set) and Philadelphia (where Oyetimein is from). When telling stories about inner-city black folks, Oyetimein is attentive to and interested in the beauty, not just the urban blight: “I feel like the majority of images that we see about black people in the inner city deal with the horrible effects of poverty, and while that might be a circumstance, the other thing that is true is the never-ending ability of black people to create beauty. What’s really important to me is to show how black people positively impact the culture of America.”

In coming months, Oyetimein will continue to make work that impacts audiences, focusing on two politically biting satires. In April she will head back to Philadelphia’s Theatre Horizon to direct the world premiere of James Ijames’ White, a piece based on the intersections of gender, race, sexuality, and art, then return to direct Robert O’Hara’s Barbecue for the Intiman in June. She is looking forward to flexing her political artivist muscles by making audiences laugh and think critically. “I truly believe that theater has the power to change hearts,” she says. With Milk Like Sugar, there’s little doubt she’s doing just that. Milk Like Sugar, ArtsWest, 4711 California Ave. S.W., artswest.org. $17–$38. All ages. Ends March 25.

stage@seattleweekly.com