The catalyst for Liz Mputu’s latest project was frustration. The nursing student was spending time in New Orleans, and living behind a Voudou priestess’ house. “Once I heard drumming and chanting that sounded like African music, and I looked outside and there were a group of white people. She was white herself, even though she called herself a modern Marie Laveau, a Louisiana Creole practitioner of Voudou. I felt upset. I wanted to make something like that for black people, by black people.”

The annoyances from that day bore the fruits that became LVLZ Healing Center, Mputu’s current exhibition at the Georgetown art space Interstitial. The show features “portals of healing”—what Mputu calls “art therapy pods.” The space is dim except for light emanating from egg-shaped chairs and the pods themselves, delineated by opaque, surgery-room curtains. Each pod “has a different healing attribute”: an assortment of video media and physical objects such as Himalayan salt lights, Mputu’s handcrafted Voudou dolls, apothecary bottles, and “affirmation apples” (which when squeezed play a prerecorded confirmation from Mputu ).

As a holistic health purveyor and a person of Congolese descent, Mputu has been studying African spirituality, seeking insight into how their ancestors viewed illness and well-being. “I was so desperate to find gods in my image. In my research, I’ve found Kimpungulu, and Maman Brigitte in Voudou.” Mputu also notes that they’re informed by mentors in their current city, Orlando, who incorporate agriculture and harvesting into African healing practices.

Mputu wanted the space to resemble a clinic and invoke a hospital as the typical association for “health” or “care.” Yet the health-care industry and wellness are often two distant matters, the former dominated by profit-driven interests and prohibitive medical expenses. Mputu positions the pods in LVLZ Healing Center in dialogue with the shortcomings of hospitals by appearing on the screen to guide viewers through relaxation exercises. This creates a new relational possibility for intimacy in what for many is a sterile and hostile environment.

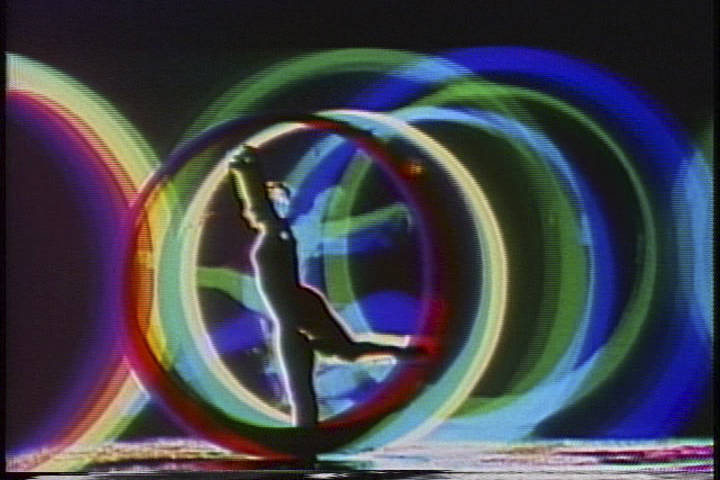

While Mputu calls on the past for long-enduring spiritual practices, their stylistic choices reflect a strong connection with contemporary media. The videos in the pods are bombastic and flashy, with liberal samplings of gifs and stock photos, rough editing techniques, and plenty of emojis. For Mputu, the aesthetic is a rhetorical choice. “It’s reflective of the visuals of memes, how people connect and share ideas online,” Mputu tells me. “Laughing at these kinds of rough images is healing for me, because I often feel isolated in Orlando. I like how playful it can be to learn, it doesn’t always have to be academic.”

The exhibition is supported by Black Embodiment Studios, started by UW assistant professor Kemi Adeyemi, who focuses “on the methods black queer women have for creating space for themselves in the contemporary city.” BES offers opportunities for students to write long-form pieces of cultural criticism and a peer group for workshops and edits. As an extension of the partnership, Mputu will give an artist talk to BES members in October.

“It just feels energized,” Adeyemi responds when I ask her what she liked about Mputu’s work. “I can’t really explain it. It’s not the kind of thing that can be distilled in a neat, eight-word headline. My lack of facility with explaining it is exactly why I like it.”

Mputu’s work eludes classification: It moves through different media and platforms, from YouTube to the niche new-media hub New Hive to secret groups in the cobwebbed corners of Facebook. Mputu is often lumped with other new-media artists such as Molly Soda, Amalia Ulman, and May Waver, who similarly gained recognition for exploring femininity, sexuality, care, and knowledge through the physical body through social-media platforms. Mputu could be called a “feminist net artist,” a category that swelled large in the early 2010s and has been deflating ever since; however, the reception of works within this canon is uneven.

Take, for instance, the Argentinian-born Ulman’s Excellences & Perfections (2014), a project wherein Ulman posted Instagram photos that gradually depict the artist undergoing a drastic makeover to a growing audience. When the project concluded, the art world celebrated. The piece is archived as an online exhibition by New Museum, and Ulman was lauded by publications like Elle as “the first great Instagram artist.” Mputu’s similar project in the same year, The Stages of My Black Social Awakening: An Instagram Guide, presents a similar examination of the self-monitorization and performativity that social media encourages, specifically in relation to black people. Not only was the reception more sparse, but Mputu even received backlash. Mputu’s creative outputs online are often followed by commenters who accuse the artist of being driven by attention, doubting any intentionality outside of narcissism.

To Adeyemi, the denial of Mputu’s artistic legitimacy is related to a general dismissal of black artists. “It makes me hot with rage, the concept that it isn’t performance at all. And that’s my drive to start Black Embodiments Studio. Let’s take these people seriously, let’s treat their work with rigor. Let’s assume that when black artists are using their bodies, they have thought about all the ways that their bodies will be read.”

“I honestly wouldn’t care if suddenly the art world forgot about me tomorrow,” Mputu tells me casually toward the end of our conversation. For Mputu, the purpose is healing and building community, no matter your geographic location. Art-making and technology have been a means to do so, but not an end in themselves.

LVLZ Healing Center: IRL Application of Digi-Manifestation, Interstitial, 6007 12th Ave. S., 3rd floor. Ends Oct 28.

visualarts@seattleweekly.com