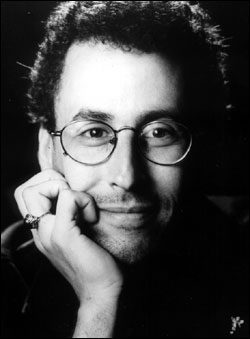

TONY KUSHNER HIT the front lines of American political theater when his Angels in Americaa “gay fantasia” that managed to take on AIDS, Reagan, Roy Cohn, the Rosenbergs, and the more private pains of ordinary peoplewon both the Tony and Pulitzer after its debut in 1993. In a time when many artists were content to separate their outspokenness from their output, Kushner focused squarely on the fact that our political selves are inseparable from every other facet of our being.

His most recent work, Homebody/Kabul (playing now at the Intiman, which debuted on Broadway in 2001, continues that challenge. Written well before 9/11, the play contemplates the effects of Western willful ignorance on our conduct of foreign affairs. I spoke to Kushner recently by phone.

Seattle Weekly: Why did you write about Afghanistan?

Tony Kushner: I’ve been interested in Afghanistan for a very long time. I followed the news during the time of the Soviet invasion and was fascinated by the mujahedeen [Afghan rebel forces] war and the Reagan administration’s response to itwhich seemed to me legitimate in the sense that the mujahedeen were obviously very brave people who were fighting against an incredibly aggressive invader, and out-armed and outnumbered. I always assumed [though] that whatever Reagan and his friends were up to was ultimately going to prove opportunistic. And it turned out to be the case that they were basically trying to give the Soviet Union a black eye and not really in any way interested in life in Afghanistan after the Soviets. This country, ostensibly intending to assist the mujahedeen, actually created a situation of heavily militarized chaos once the Soviet army had been defeated.

One of the things that really got me going when I wanted to write the play in 1997 was that I think it’s easy to make decisions that produce tremendous problems elsewhere. I mean, we should never have invaded Iraqthat was a terrible mistake and we’ll be paying for it for many decades to come. The question about whether or not we should simply withdraw now that we’ve destabilized the entire country I think is very complicated, but the sort of “let’s get our troops home and let’s get out of this” thingwell, it’s too late for that. Any [kind of] washing your hands of such things is not always an option, and I think that’s something that I wanted to explore in the play.

There’s a great line at the beginning of the play about how so many of us are “overwhelmed and succumbing to luxury.” Are you trying to shake us out of comfort?

Comfort and a certain kind of arrogance. I think it’s a play about surrenderingsurrendering assumptions, and surrendering a kind of culturally based arrogance that makes us believe we know exactly what a situation requires and what to do about it from a distance. [It’s about] approaching a situation in which we intend to take action with a degree of humility, and a recognition of our lack of clarity, and recognizing what kind of moral obligations those place on youwithout the kind of melodramatic “cowboy politics” that our president, or whatever he is, is so fond of.

In Angels in America you were able to commingle a very large issue with a more intimate grief. How difficult was it to accomplish that same thing here?

Part of the danger is you run the risk of trivializing a large scale political conflict as background or metaphor for personal journeys. I struggled to balance [the play] so it never rested comfortably in one place or the other. [And I’m] a gay, Western, American Jew, so it’s not a documentary at any point, either. It’s always a work of fantasy and imagination. I think this play claims a lot of space for these Afghan characters who matter as much ultimately as the Western characters do and have as much stage time.

Do you purposefully set out to challenge an audience?

Well, none of it is planned in that sense. I think one of the ways to avoid boring people is to keep them working. I mean, sometimes an hour-long play can seem like five hours because you know two minutes into it where you’re going, and [there’s] nothing to do but to sit around and wait for it to arrive. Surprise and the unexpected is an important part of keeping people entertained, and that’s basically what I do. There are some theater artists who work with boredom as kind of an experienceit’s an interesting experience but it’s nothing I do. I’m terrified of it. But I never consciously set out to stump or baffle people or scandalize them in any way. I feel that I’m asking questions that I genuinely do not know the answers to and have to kind of look for the answers. The most interesting questions in politics and personal life are the questions for which there is no single answer, and I think people are hungry for that kind of an entertainment. It’s one of the pleasures that art provides.

Do you think we’re too affected by nostalgia or false sentiment in the arts and as a nation?

Well the falseness is the problem. I mean, the new is very stressful. The new is ugly and unformed and frequently unappetizing and always feels scary and sometimes genuinely is scary because we don’t have any guarantee that it’s all going to work out. And right now it doesn’t look like it’s working out at all. I think to do what Reagan did, and to do what these clowns like Bush want to doto actually turn the world backthat’s where the most monstrous crimes come from: This fantasy that you can actually turn the engine of the world into reverse and go back to something. You can’t do that, but you can miss it terribly, and sometimes what you miss is really worth mourning. I mean I’m 47 years old and when I first arrived in New York in the ’70s, I saw theater that was truly astonishing, and I have to honestly say that I don’t know that anybody’s doing theater as good as that. The theater, of course, is always an art about the disappearance of what you love and its irretrievability. I think that nostalgia is the sort of cynical manipulation of that decent human emotion of loss and mourning for the purposes of advancing a pernicious ideology.

How important is it to be political in the arts right now?

You can’t find any important work of American art, in theater or anywhere else, that doesn’t have a very powerful political dimension. [But] whatever you do with your day joband writing plays is what I dois no replacement for activism, which is a necessary part of being a citizen in a democracy. And not to be foolish and think that writing a political play is going to do it, because there’s only one thing that does itorganizing and voting and demonstrating and fund-raising and e-mailing and joining groups. Art is not [it]. I mean, I admire theater groups that mobilized around the antiwar effort, but I don’t think that’s essential, and it can be incredibly misleading because you wind up with everybody getting up and doing sort of a performance piece about the war. What we really have to be doing now is organizing people to get out and vote for the candidate that the Democratic party nominates for president. It’s the one thing that counts right now. And nothing else does.