“Being a symbol can be very exhausting,” Nadeshiko, played by Ina Chang, says to the audience lightheartedly. Providing a historical frame for the audience, the entertaining, elderly narrator shares a story about a delicate and shy brand of femininity, constructed in Japan during WWII, that echoes that of a pink, fragile flower named nadeshiko—the name given to the women who took care of the kamikaze pilots in the town of Chiran before their suicide missions near the end of WWII.

Nadeshiko is a new play by Seattle-based theater artist Keiko Green, produced by Sound Theatre Company. The multigenerational story follows two women, a contemporary American sex worker and a nadeshiko enlisted by the Japanese army to comfort the kamikaze pilots. “The fetishization of Asian women didn’t start in the West. The stereotype of giggling, shy, submissive women started in the East—it just got taken to a whole new level here in the West,” Green writes in the production’s program. Through innovative historical framing and nuanced character development, the play’s two narratives look at the development and construction of idealized Japanese beauty standards.

With a quick flip forward in time, the scene following Nadeshiko’s story delves into the symbology of these standards today. Japanese-American sex worker Risa (played by Maile Wong) and her client, the White-Haired Man (Greg Lyle-Newton), discuss Risa’s decision to engage in fetish-based sex work. In Nadeshiko, the narrative around contemporary sex work is subtle and pointed, particularly in the ways race shapes sexualization. Risa relays the everyday reality of being stared at and objectified as a woman of color. “Look at that person, look at that person that’s strange,” she shares with her client-turned-confidant, reflecting on the way white people gaze at her. “If I’m going to be stared at, then why not make some money off it, you know?” she says, exploring what it means to make money fueled by idealization.

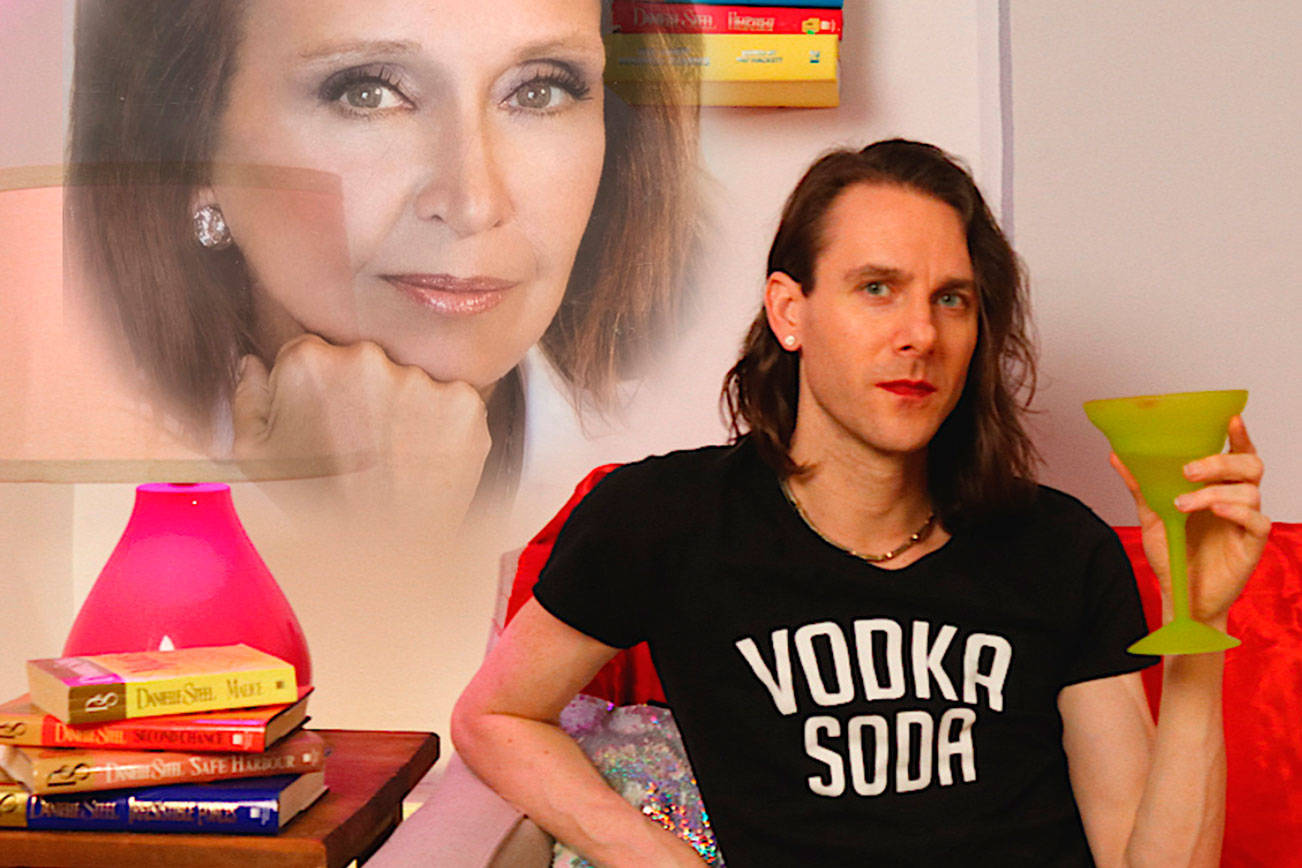

Nadeshiko’s and Risa’s narratives transition smoothly between time periods, in large part helped by Sound Theatre’s production, directed by Kaytlin McIntyre. The transitions are cushioned by Luke S. Walker’s projection designs, placed upstage center. From videos of fetishized Japanese femininity in pop culture (Avril Lavigne’s “Hello Kitty” music video) to scenes of Chiran, the kamikaze base camp, in 1945, the projections support the shifting time periods by placing us in the continuum of their narrative contexts.

In one particularly striking scene, Mi Kang plays both a young nadeshiko and Risa’s cousin Sue. In seconds, Kang transitions from crying over a soldier’s impending death to chatting with her cousin about wearing traditional Japanese clothing in her work as a cam girl. “Look how fucking cute I look,” she says to Risa, running to her bed to set up her room to align with her fetish play for the day. The combination of history and contemporary narrative is impeccable, a testament to Green’s skill as a playwright. “Every human experience involving race is colored by historical context,” Green shares in the program, and Nadeshiko exemplifies theater’s power to complicate and dismantle the persistence of racialized stereotypes. Nadeshiko, Center Theatre, Seattle Center Armory, soundtheatrecompany.org. $15–$25. All ages. Ends May 16. stage@seattleweekly.com