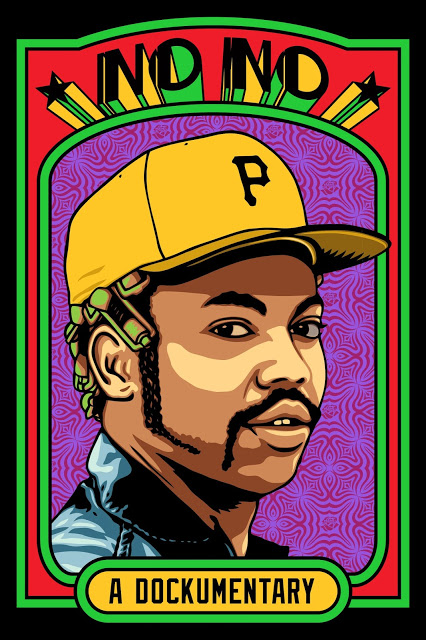

Just as the Seahawks begin their season this week, here’s a profile of an outspoken black man from the generation before Richard Sherman. Raised in Compton, Dock Ellis pitched in the majors from 1968–79. He and his peers on the minority-heavy Pittsburgh Pirates—where he became a star and helped earn a World Series title—were of the generation that followed Jackie Robinson into pro baseball. Racism was still very much a part of the game, but so was the Black Power movement. The young Ellis had meekly experienced the segregated motel rooms of the South during his minor-league days, and his stardom unleashed a strong new voice. Not for nothing was he branded “the Muhammad Ali of baseball,” an image he cultivated, he said, “because it’ll make me money!”

Less interesting than the man is the hook for Jeffrey Radice’s first feature doc: the now-famous no-hitter Ellis threw in 1970 while on acid. He was so high, in fact, that he later sadly claimed that he couldn’t even remember that game. (Dropping in for a cameo is Ron Howard, who included Ellis in his 1986 Michael Keaton comedy Gung Ho, casting I’d completely forgotten; and damn if Howard doesn’t get teary over Ellis’ inability to recall what ought to have been the greatest day of his life.) Still, there are vintage clips of the game, and Radice makes good use of the archives in recounting Ellis’ life. He adds fresh interviews with Ellis’ family, friends, and former teammates, yet he scored only a little late-life footage of Ellis himself, who died of cirrhosis in 2008—though clean for decades, finally a casualty of his earlier alcoholism and drug abuse.

Even for non-sports fans like me, No No is fascinating for its ’70s collision of politics and PEDs—the latter chiefly amphetamines (“greenies”), though augmented off the field with copious amounts of booze and coke to cope with the pressures of being young, famous, yet insecure. The Nixon-era politics are explicitly racial, direct in a way we’re not accustomed to discussing so pointedly today—until something like Ferguson, Missouri, comes along. Baseball may not be a microcosm for America, but it’s eye-opening to hear these long-retired sluggers—black and white—talking about the sudden integration of the locker room. Ellis drew headlines by wearing his hair in curlers—a calculated cultural provocation, but also part of his tough-guy, don’t-give-a-fuck persona. This, too, may be why he threw so many beanballs; though Radice doesn’t ignore Ellis’ violent tendencies, which extended to beating his wives.

Ellis’ career reflects the unbridled era of Ball Four and North Dallas Forty, when salaries were much lower and players had less to lose with their candor. (Ellis even co-wrote a biography with the poet Donald Hall.) Since his career decline and AA years aren’t very interesting, one wishes that Radice had widened his focus from Ellis’ unintended LSD victory—an accident of vacation scheduling, really—to the culture of the sport that made him both a hero and a martyr. (Note: Producer Chris Cortez will attend opening night.) Runs Fri., Sept. 5–Thurs., Sept. 11 at Northwest Film Forum. Not rated. 100 minutes.

bmiller@seattleweekly.com