We’re an instant-image society now, with no time to wait for traditional film processing. Even the Polaroid camera seems too slow, too limited, for the urgency of Tumblr and Facebook and online photo sharing. Yet there’s a curious, anachronistic, almost instantaneous quality to the large-format portrait photography of Daniel A. Carrillo, one of the fall–summer beneficiaries of the city’s Storefronts Seattle program. He’s presently sharing space (in back) with the Youth in Focus photography program; it’s one of 10 such studio/residency/gallery tenancies in what would otherwise be empty retail space in Pioneer Square and the ID.

“Photography was always a side project,” Carrillo explains during the setup for a portrait session earlier this month. Born in Mexico, raised in California, and a Seattle resident since 1997, he’d primarily been a printmaker until discovering wet-plate collodion photography in 2009. It’s one of the earliest photographic technologies, devised circa 1850, in which the light-sensitive emulsion chemicals are still damp when inserted into a view camera. All those stiffly posed Mathew Brady prints from the Civil War? They were made via collodion process. (The “dry” daguerreotype process, which required shorter exposure times, replaced it by the 1880s, though the collodion process survived another 100 years for product and technical photography of things that couldn’t move or blur.)

Gesturing to the huge 1939 view camera on a vintage wooden stand, Carrillo says, “I got this whole thing from a guy in Chicago for about $1,400.” You could spend as much—or far more—for high-end digital gear; and this setup requires no costly PowerMac or Photoshop to manipulate the image, only regular trips to the chemical-supply store. To prepare the plates and develop them in the the darkroom in back, he adds, “All I need is a little bit of running water.”

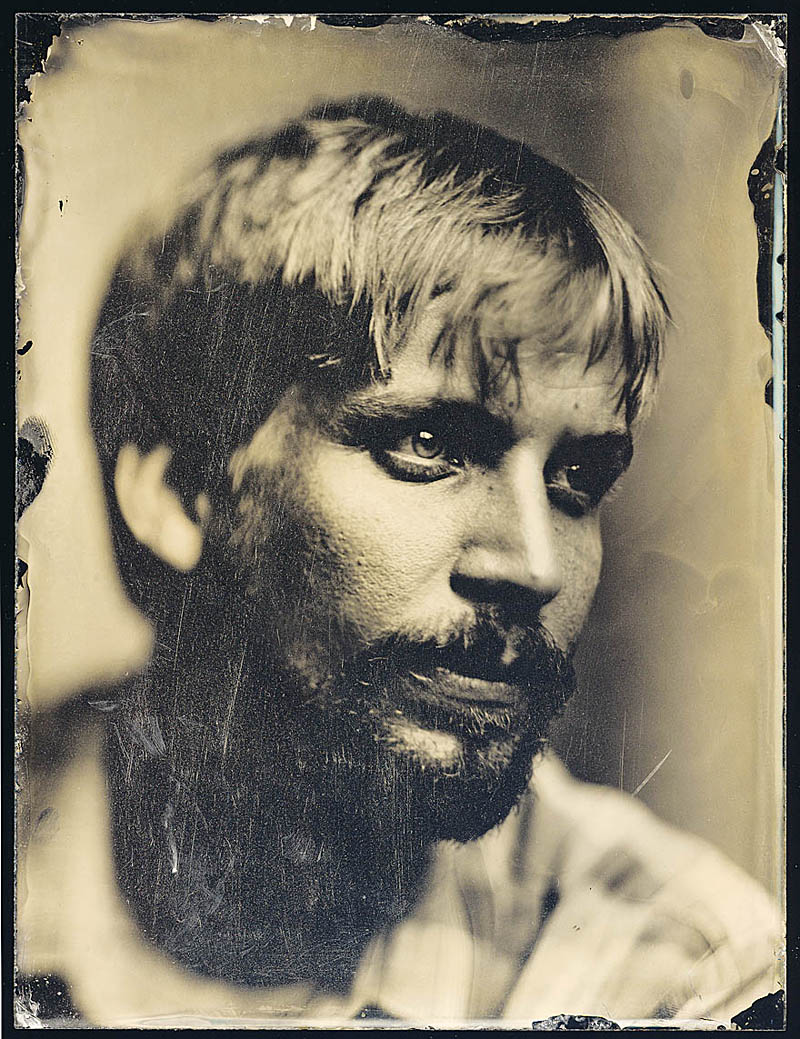

His first big photo project is portraits of his friends in the Seattle art scene. “They understand if they have to sit for a while,” Carrillo notes, since indoor exposures require being absolutely still for six to eight seconds, measured by stopwatch. (Aiding them is a metal head brace that might have come from a Victorian-era dentist’s office.) Each portrait session is an experiment as Carrillo varies the amount of silver nitrate in the emulsion, the duration of the exposure, and the arrangement of the studio lights.

“People readily accept the limitations,” he says. “It’s far from perfect. It’s real finicky. Things go wrong all the time.” Each plate, after Carrillo delicately applies the liquid emulsion, has a built-in deadline; it’s only light-sensitive when wet. Thus, from chemical mixing to exposure to processing, he explains, “It’s pretty forgiving, but it all has to be done within about 10 minutes.”

With a solo show planned for Greg Kucera Gallery next year, Carrillo can only guess how many artist portraits he’s done to date. “It’s easily over 100. Maybe 150. I really haven’t kept track.” (Many can be viewed on Flickr or his website, where commissions are also accepted.)

Several artists have brought him work-in-kind for their sessions, for example Ballard artist Joey Bates, who meets us with a cut-paper nude. (He’ll have a solo show at the Gage Academy of Art Oct. 18–Nov. 14.) Having done portraits himself, how does he feel about being the model instead of the artist? “It is a reversal, but I feel pretty comfortable with it,” says Bates. He patiently waits while Carrillo fusses with the lights, mixes the chemicals, and arranges his static pose for the long exposure. (“Chin up. You can’t blink.”) One problem, we discover in the darkroom following the first exposure, is that Bates’ too-blue eyes are bouncing the light back like mirrors—they read like white splotches on the negative-image plate.

Unlike daguerreotypes, where the print is the one-and-only image, collodion-process photography allows for multiple contact prints. And, like a Polaroid, you get to see it quite soon (provided a darkroom is at hand, which it always is, since fresh chemicals are always required). The final contact prints are deep-grained, splotchy, dense in the gray scale. Carrillo doesn’t mind the restricted palette. “I’ve always worked in black-and-white,” he says. “I’ve always resisted color.”

Only the blue spectrum of light is captured, yielding an eerie, almost funereal tone. In the evening’s best exposure (of three), the young and friendly Bates could be a Union Army soldier headed into battle. Or later, another anonymous corpse in a Mathew Brady photograph.