I’m a Sherlockian, hardcore. It’s like being the guy who puts on Vulcan ears to watch his favorite Star Trek episodes. I’ve written a much-produced play, Sherlock Holmes and the Case of the Christmas Carol, which debuted at Taproot in 2010, and a yet-unpublished Holmes novel. I even own—though seldom wear—a deerstalker cap. And once a month I meet with like-minded fanatics at The Sound of the Baskervilles gatherings (more on that later), where both Arthur Conan Doyle’s original texts and the new Sherlock Holmes TV shows are avidly discussed.

Suddenly, thanks to those shows, casual Sherlock fans are everywhere—latecomers, we purists scoff. There have never been more high-profile adaptations of Sherlock Holmes than today. Robert Downey Jr. and Jude Law have starred in two recent Holmes action movies, with a third in the works.

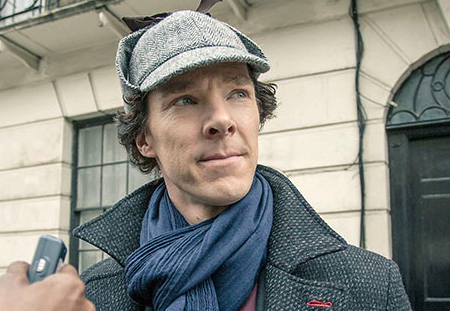

On television we have Elementary on CBS, starring Jonny Lee Miller, and the BBC’s Sherlock, starring Benedict Cumberbatch. Both update Holmes to the contemporary world, though it’s the British version—which just streamed its third season on Netflix—that’s drawn the most critical approval, mine included.

Sherlock

comes in big, meaty 90-minute episodes that feel like feature films, free of commercial breaks and the drawn-out storylines that plague American TV. While Sherlock’s London is contemporary, we still detect the underlying Victorian metropolis—the gristle and grit of the wonderful old city. The third season of Sherlock is, I would argue, the best yet, as it focuses on the subtleties of the very human friendship of its two central characters.

(Here let’s stipulate that the pedestrian, New York–set Elementary comes across as a pale copy of Monk or House ; Miller is mostly wasted playing yet another eccentric detective with a ho-hum drug habit; he’s not helped by Lucy Liu’s female yet otherwise unremarkable Watson; and the scripts are utterly mundane.)

Why is Sherlock so good? I am forced to concede that the show’s creators, Mark Gatiss and Stephen Moffat, are even bigger Sherlock nerds than I. They previously helped reboot Doctor Who, and they enliven this show with fancy edits, wipes, fades, and freezes that demonstrate Holmes’ mental processes. His mental observations—a worn collar cuff, a bit of dog hair, too much makeup—even appear on the screen in neat little white script. Graphics show us maps and diagrams as Holmes races through his “mind palace” in search of the correct clue. They also stuff each episode with references to the original Conan Doyle stories. In one repeating trope, a series of clients present their cases to Holmes in a flowing montage, with him providing solutions at lightning speed.

Granted, the show does make occasional missteps, puffing up its protagonist past superhuman and into superhero: Holmes surveys London from a rooftop as if he’s just been summoned by the Sherlock Signal; he leaps on a motorbike like James Bond.

The greatest pleasure to Sherlock is the perfect casting of Cumberbatch as the detective and Martin Freeman as Dr. John Watson; both are clearly having the time of their lives in these iconic roles. Cumberbatch is an actor built to play gods and demons (see: Star Trek Into Darkness). He’s angular and not quite handsome, with a searing intelligence and patrician air. Like the two other great screen Holmeses, Basil Rathbone and Jeremy Brett, there’s a thin, quivering element to his performance that shimmers with impatience. Unlike those earlier actors, however, Cumberbatch embraces Sherlock’s least likable elements. When a policewoman calls him a psychopath, he replies, “I’m a high-functioning sociopath. Do your research.”

Freeman, on the other hand, has cornered the market on honorable everymen, from Arthur Dent in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy to his current run as Bilbo Baggins in the Hobbit movies (where Cumberbatch gives voice to the dragon Smaug). His Watson is the appropriate heart to Sherlock’s head, as well as being the perfect audience stand-in—merely bright in contrast to Holmes’ brilliance.

Now you might assume that dyed-in-the-wool Sherlockians—who famously refused to let Conan Doyle kill his hero—might hate a TV series that transports our beloved Holmes from a London of hansom cabs and telegrams to the modern era of motorcycles and cell phones, and even ditches the famous deerstalker. Tradition reigns at our Sound of the Baskervilles group, a scion chapter of the Baker Street Irregulars, who’ve been meeting in New York since 1934. (The SOBs, as we’re known, first convened in 1980.) Yet just the opposite. For all the reasons cited above—the writing and performances, the respectful treatment of Holmes and Watson—we love the new Sherlock.

But there are downsides for us Sherlockians when suddenly forced to share our ardor. As a panelist at Sherlock Seattle, a convention held each fall on Capitol Hill, I was bemused to find myself sharing space with fans of the new BBC show who knew little of Conan Doyle’s old writings. A large number were women ranging from adolescence to middle age who love Cumberbatch’s Sherlock. They particularly love reading and writing fan fiction that features characters in a variety of erotic combinations (Sherlock/John, Sherlock/Moriarty, Sherlock/Lestrade, etc.). Yet I did find them remarkably open to learn more about Conan Doyle’s original stories.

And Sherlock’s third season does affectionately acknowledge such fan desires—we’re teased with a fantasy involving Moriarty and Sherlock heading for a kiss—without letting them run the show. Instead of heading into the gay, Season Three brings a fiancee for Watson, and their wedding occupies the lion’s share of Episode 2. This culminates in an astonishing set piece where Holmes delivers the absolutely worst, and most wonderful, best-man speech ever.

By the concluding Episode 3, even Sherlock has a girlfriend, apparently settling the debate about his lack of sexuality—though their relationship is, predictably enough, not what it seems.

Cumberbatch and Freeman have already signed up for two more seasons of Sherlock, and the series now seems comfortable enough to play with the weight of inherited houndstooth tradition. Some moments are even meta, as when Holmes heads to a press conference, unironically wearing the once-maligned deerstalker and declaring, “Anyway, time to go be Sherlock Holmes.”

Three years in, there’s a consensus among both newbies and my fellow Sherlockians: Just as Freeman is a definitive Watson, Cumberbatch is this generation’s choice for the Great Detective.

arts@seattleweekly.com