If you could shine a blacklight on American pop culture, you’d see Harvey Kurtzman’s DNA splattered all over it. And not just a little bit. A lot. Everywhere. (Under a microscope, it would look like Alfred E. Neuman’s face.) It’s hard to overstate how Jackson-Pollocked America’s pop culture, humor, and sensibilities are with Kurtzman (1924–1993). And yet, I’ll make you a bet: If you sample any random 10 people—not just on the street but at a comic con—you’ll be lucky if one or two light up at the name.

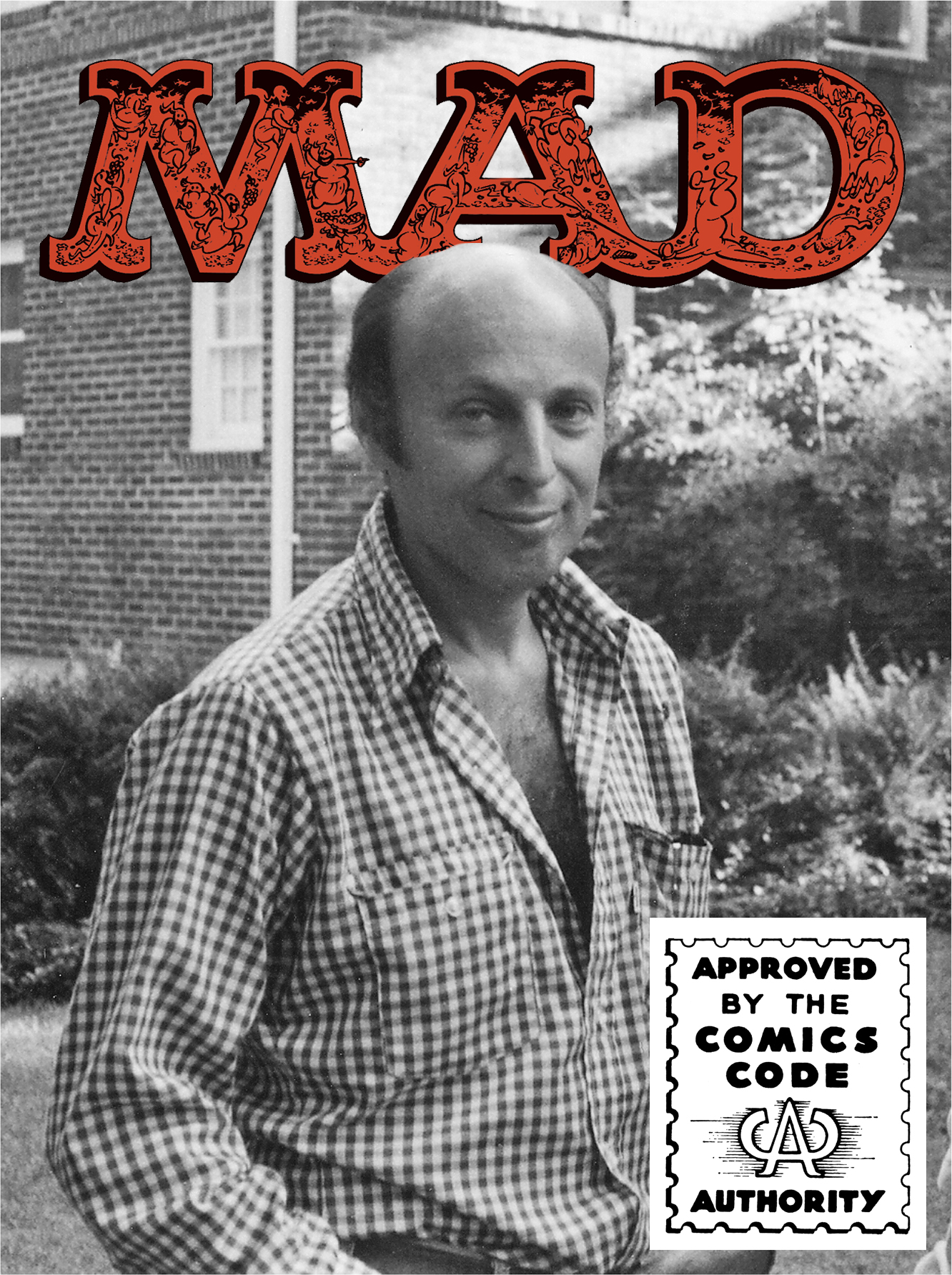

An impressive new biography aims to fix that, starting with the title: Harvey Kurtzman, The Man Who Created Mad and Revolutionized Humor in America ($34.99, Fantagraphics). This 642-page doorstop from award-winning comic-book historian Bill Schelly is a thorough, loving chronicle of Kurtzman’s life, struggles, art, and influence. I didn’t want to place it on the shelves alongside my beloved Mad and EC Comics archives. It made me want to take them off the shelves and sit on the floor surrounded by them, giving every page a fresh look.

Maybe Mad is like the movie John Carter—based on Edgar Rice Burroughs’ John Carter of Mars. Just hear me out: It was so widely influential, over so many decades, and so copied and appropriated, that the original doesn’t turn heads anymore. When’s the last time you bought an issue of Mad?

Founded in 1952, Mad reached a mid-’70s circulation peak of two million per issue, Schelly tells me. “Now I believe it’s around 140,000.” When I interviewed Mad editor Joe Raiola for The Seattle Times in 2009, the magazine had begun taking advertising and its print existence was uncertain. Schelly points out that may also be part of the overall decline of print media. (Maybe you’ve heard the newspaper business is on life support.)

But what Kurtzman and Mad did was unprecedented: mocking and satirizing authority, commercials, and consumer culture—pretty much everything—with an irreverence that was thrillingly bold in the commie-paranoid, conformist, Leave It to Beaver ’50s. By the time of the Vietnam War and Nixon, it was a major cultural force.

Chatting with Schelly recently at a Lake City Starbucks near his home, we wondered what Kurtzman would’ve thought of Starbucks’ hilariously tone-deaf “Race Together” misstep. A retired business analyst, Schelly spent three years researching and writing the Kurtzman book. As a shorthand way of quantifying the work that went into it, he points to the whopping six pages of acknowledgements and 27 pages of end notes.

Born in New York to a working-class, Daily Worker-reading Jewish family, Kurtzman was raised during the Great Depression. A comics prodigy, he won contests as a teenager and dropped out of college to enter the industry. At William Gaines’ EC Comics (legendary publisher of Tales From the Crypt and Vault of Horror), he notably created adventure and war titles like Two-Fisted Tales and Frontline Combat that abandoned the usual jingoistic, gung-ho propaganda of ’50s comics.

Kurtzman was pro-labor and distrustful of big business. He ridiculed authority figures of all stripes and humanized our enemies. He would’ve fucking hated FOX News, I tell Schelly, and vice versa. In fact, says Schelly, “The FBI investigated him.” And more: During his employment by EC, where he edited Mad from 1952–56, the entire comics industry was investigated by the infamous Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency. From that came the Comics Code Authority, though Mad was EC’s only title to survive the clamp-down. Then, just five issues after Mad went to a magazine format, Kurtzman abruptly left.

He then freelanced—including Playboy’s notorious Little Annie Fanny—and taught to the end of his life. Among the young artists he published in the ’60s were R. Crumb—thus becoming a forebear of underground comix—and Terry Gilliam (of Monty Python). “He was their god,” says Schelly. In his introduction to the book, Gilliam argues that “Harvey’s influence was the hidden epidemic that changed much of our society for the better.”

In retrospect, Kurtzman left Mad prematurely. He’s like George Lazenby’s 007, I crack to Schelly. More like Sean Connery’s, Schelly corrects me. Fine, fine. But hear me out again: Lazenby planned to jump from Bond to a big action picture with Bruce Lee—then Lee died. After a money dispute with Gaines, Kurtzman jumped from Mad to Hugh Hefner’s Trump—which lasted two issues. He died with $35,000 in the bank after watching his EC colleague Al Feldstein, who edited Mad into the ’80s, get rich off his creation.

And speaking of riches, I tell Schelly, Kurtzman wouldn’t have lined up to see Marvel corporate brand-stravaganzas like Avengers: Age of Ultron. No, he says, Kurtzman would have considered that an obscenity: Dumb entertainment designed for profit, not art. It’s the kind of thing Mad—or at least Kurtzman’s original Mad—would’ve satirized.

Today Mad mag sneaks out six times a year with a sliver of the impact it once had. Yet Saturday Night Live, The Daily Show, The Colbert Report, and The Onion were all born of Kurtzman’s influence and bathed in his iconoclastic sensibility. Above all, says Schelly, Kurtzman was a truth-teller. “He didn’t think art should just be escapism.”

markrahner.com

UNIVERSITY BOOK STORE 4326 University Way N.E., 634-3400, bookstore.washington.edu. Free. 7 p.m. Thurs., May 7. (Rahner’s Special Ops podcast conversation with Schelly is available Thursday on bjgeeknation.com and iTunes.)