Ida

Opens Fri., June 13 at Sundance Cinemas and SIFF Cinema Uptown. Rated PG-13. 80 minutes.

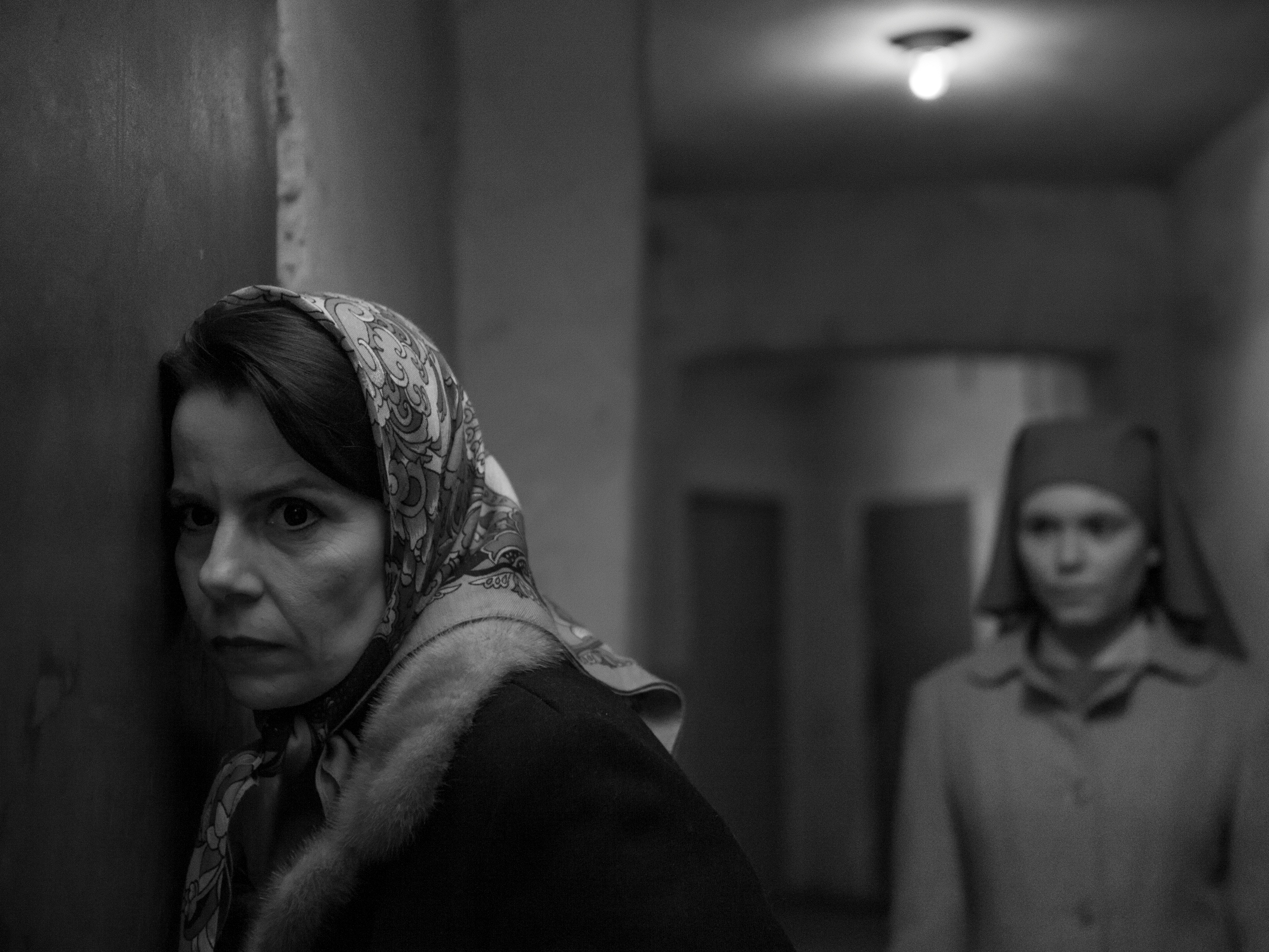

After the calamity of World War II, your family exterminated by the Nazis (or their minions), how important would it be to reclaim your Jewish identity? That’s the question for Anna, 18, who’s soon to take her vows as a Catholic nun in early-’60s Poland. Now early-’60s Poland is not a place you want to be. The Anglo-Polish director Pawel Pawlikowski (Last Resort, My Summer of Love) films his black-and-white drama in the boxy, old-fashioned Academy ratio, like some Soviet-era newsreel. You can’t smell it, but the negative seems to have been developed in a bath of vodka, urine, and cow shit. And that’s the dominant impression of the outside world for virginal Anna (Agata Trzebuchowska) when she’s sent to visit her unknown aunt Wanda (Agata Kulesza), a drunken former Communist prosecutor who’ll fuck any man she fancies. Beyond the convent walls, the world is a sorry place; and it only contains more sad tales.

Anna, she discovers, is a Jew—an orphan delivered to the church as an infant during the war, birth name Ida. Wanda insists they find their family homestead, and a desultory road trip ensues. The surly peasants won’t talk to them; Wanda smashes their car; and Anna’s too shy to flirt with a handsome, hitchhiking sax player (Dawid Ogrodnik) who invites them to a gig. (His god is Coltrane, a far different cat than Christ.)

From The Pawnbroker to Schindler’s List, the canon of Holocaust movies has been fairly well exhausted at this point. Pawlikowski doesn’t dwell on the familiar bones or atrocities; instead, he shadows two women—Wanda being the more interesting character—with different approaches to the past. Wanda’s the former resistance fighter scarred by the war. Anna’s the new generation who’ll hear the Beatles on shortwave radio. But will that—and Coltrane—be enough to sustain a life behind the Iron Curtain?

The usual Holocaust tales celebrate endurance or escape. Ida suggests something simpler and deeper about survival and European history in general. Sometimes you just can’t come to terms with the past. And why should Anna, so sheltered, be forced into such reckoning? (Wanda’s eyes, always open, admit only sorrow.) Pawlikowski and his co-writer, English playwright Rebecca Lenkiewicz, poke at the pit graves and pieties of the Cold War era and find an unlikely sort of strength for their heroine: the courage to turn her back.

bmiller@seattleweekly.com