His favorite targets include the homeless, Asian shop owners, security guards, and cabbies. With an unwavering stare and nerves of steel, he aims his video camera at them, seemingly intent on eliciting anger, confusion, and anything else his unwilling subjects care to muster.

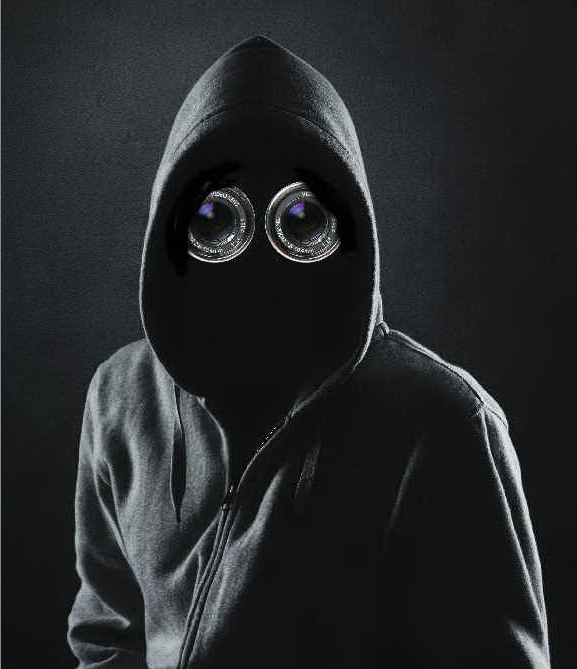

Known only as Surveillance Camera Man, this provocateur’s YouTube videos have become viral, controversial hits, most yielding over 100,000 views. He’s uploaded five compilations since October 2012, each following a simple template: SCM, as we’ll call him, walks up to a stranger, usually in a public space, and silently trains his lens on them.

When the subjects wonder why they’re being filmed, his response is almost always the same: “Just taking a video.” (SCM’s face is never seen.) Each compilation runs 4 to 6 minutes and contains several clips of SCM annoying people in various locations. The clips appear to be shot with a tiny camera or cell phone, adding to the target’s initial confusion about what’s happening.

“It’s not easy to sum up the recipe of a viral video,” says Brad Kim, managing editor of Seattle’s Know Your Meme (part of the Cheezburger family of websites). He cites the “repetition of a single motif, brevity in length, elements of drama and surprise. And with the case of Surveillance Camera Man in particular, voyeurism and timeliness.”

With Edward Snowden and the NSA surveillance scandal as a backdrop, SCM’s videos might arguably be making a political/artistic point. In one early reel, he alludes to the ubiquity of surveillance cameras in public. “Look at it this way,” he says to his target. “Do you ever go to the grocery store? You know how there’s, like, surveillance cameras everywhere? It’s not a big deal.”

He’s been more silent in recent videos, leaving Internet commenters to debate whether the project is intended as art or simple trolling—like those sidewalk-slapping videos and other punk-with-a-camera stunts.

SCM’s goal seems to be to provoke rather than enlighten, and the clips make entertaining viewing—if not art that might be seen in a gallery. Sharon Arnold, owner of Georgetown’s LxWxH gallery, which sometimes features video installations, says she isn’t sure whether it’s art or not. “It’s definitely commentary,” she offers. “And it really hits home. We wouldn’t want a person recording us.”

In his only known interview, SCM e-mailed the website Photography Is Not a Crime last November. Of his project’s origins, he wrote, “I was with a friend who wanted to film a social experiment. But we didn’t have audio equipment. I explained how we could only get good audio if we pushed the camera directly into people’s faces. After the first couple of approaches, he couldn’t keep a straight face. It was all me after that.”

The in-your-face approach generally yields a hostile response—or perhaps those are the only ones SCM posts. (If people don’t get angry, he won’t get clicks.) People naturally resent being filmed without consent and having their personal space invaded.

Here’s a typical exchange, between SCM and a business-dressed guy seated outside a Starbucks, talking on his phone:

Man: “What are we doing here? I’d appreciate it if you’d go somewhere else with that.”

SCM: “It’s OK, it’s just a video.”

For a moment, the Starbucks patron seems amused, revealing a hint of a smile. He can’t believe the balls of this guy. Then he grows more agitated.

Man: “It’s offensive to me. I’m trying to have a private conversation. Could you respect that? . . . Could you please move? Do you not understand what I’m saying?”

SCM: “Calm down.”

Man: “Leave! Fuck you, ya got it! And the horse you rode in on! You have no respect for anybody. What are you gonna do, follow me around now?”

And as the target gets up to walk away . . .

Man: “You even look like a dumb fuck.”

Another common reaction to SCM is the claim that he needs permission to film them. The truth is he doesn’t, says Portland attorney Bert P. Krages, who specializes in photographers’ rights. “If he’s just recording what he’s seeing, there’s no real issue with regard to him getting releases.” That’s why paparazzi don’t need signed releases from celebs for permission to use their images for tabloids and gossip websites.

Krages adds, “The general rule in the United States is that anyone may take photographs of whatever they want when they are in a public place.” And that includes the people in those places; there is no right to privacy on the sidewalk.

In private spaces to which the public is invited, like Baskin Robbins or the Church of Scientology (both appear in SCM clips), the rules are different. There, as in most malls and stores, photography is generally allowed until someone with authority over the premises, like a business owner or restaurant manager, asks you to stop.

Krages continues, “The dicey area in this legally comes with regard to the audio portion of taking video.” Washington state has what’s called a two-party notification law, which means both parties in a conversation have to consent to its being recorded. “Once people were clearly not consenting [SCM] to record their conversation,” says Krages, “he probably did cross a line.” What about harassment or public-nuisance laws? “The mere fact that someone’s annoyed by it generally won’t be enough.”

Also, there’s no way to identify this nameless filmmaker to file a complaint. He ignored my interview request, and his YouTube page announces that “SCM does not have a Facebook or website.” Judging from his filming locations—U Village, Big W Cleaners, Lost Sock Laundry, etc.—it’s clear he roams the U District and Capitol Hill. He’s in his late 20s, according to Photography Is Not a Crime, where he declared, “I don’t see any reason to wave my hands in the air and shout, ‘Look at me! I’m the Surveillance Camera Man!’ If something I do gets a lot of attention, great. But I don’t need to be a celebrity.”

The hypocrisy of that statement, of course, is that SCM exploits the privacy of others while preserving his own. Street photographers like Lee Friedlander, Garry Winogrand, and Henri Cartier-Bresson captured subjects in public places, too, but they sought beauty in unprovoked moments. They portrayed their subjects from a respectful distance—not by creating a gotcha moment by thrusting a camera into someone’s face for lulz.

SCM may create compelling content, but his supposed message—about privacy or photographers’ rights or whatever—is muddled by his bad manners. Because his videos are so mean-spirited, they’ll never rise to be anything more than junk-food click-bait.

visualarts@seattleweekly.com