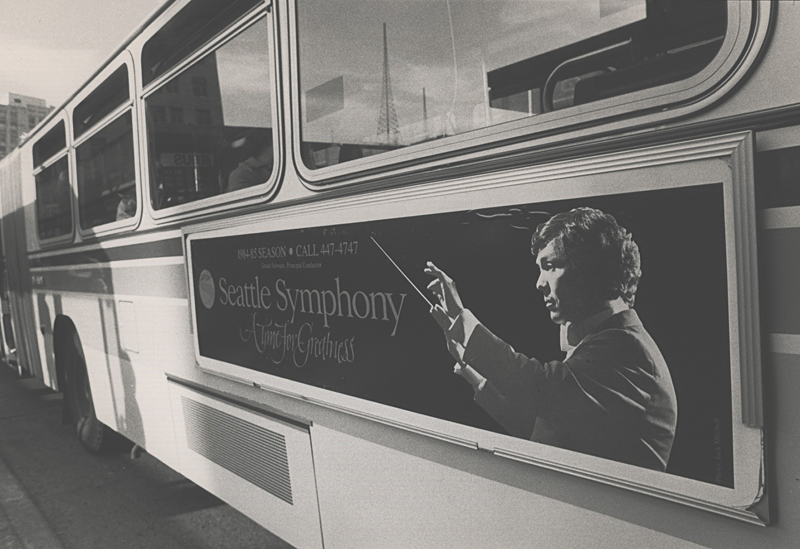

A chapter ended for the Seattle Symphony last Saturday night with Gerard Schwarz’s final performance as music director, a post he assumed in 1985 and has held for roughly a quarter of the orchestra’s history. Though he’ll guest-conduct several concerts next season, the baton now passes to French-born Ludovic Morlot—who was, if I remember right, not once mentioned by name during the spoken tributes that opened Saturday’s farewell concert.

Following those tributes, dessert came first: Philip Glass’ brief but inviting Harmonium Mountain, the last of the Gund-Simonyi Farewell Commissions, curtain-raisers written and sprinkled throughout the season to commemorate Schwarz’s adieu. Scored for strings and just a handful of winds, alluring in its shimmering textures and trippy harmonies, it ended (actually, just sort of drifted away) just as I was settling into it.

The piece Schwarz chose to cap his 26 seasons, one which he and the SSO have done magnificently in the past, was Mahler’s Symphony no. 2. The orchestra played the [expletive] out of it, various instrumental sections at times sounding golden, creamy, silken, luminous—choose your favorite adjective. The debate over applause between symphony movements was taken to a new level when Schwarz and the orchestra drew a smattering of applause during the music, after a shattering climax in the first movement.

One particular reason, I’ve always thought, that Schwarz’s most memorable performances have been of Mahler (and of other masters of the grand gesture like Wagner, Strauss, and Shostakovich) is his ability to fully milk the music’s dramatic moments without interrupting its flow. No matter how much he lingers—for that ecstatic, time-dilating sensation that the late romantics so lovingly exploited—he somehow keeps the momentum going. And no composer tests this skill like Mahler, who, in the Second’s sprawling finale, can seem less engaged with composing music than in compiling an encyclopedia of Effects to Stun an Audience With.

The Seattle Symphony’s regime change raises two big questions. One was answered in January, when the organization announced the thrilling plans for Morlot’s first season—taking daringly full advantage of the SSO audience’s receptiveness to 20th-century music, a level of trust carefully built and nurtured over the years by Schwarz. The emphasis will shift, of course, from the American composers Schwarz favored. If his efforts haven’t sparked a major, widespread revival of interest in this school, the music is readily available as highlights of his impressive discography (nearly the complete orchestral works of Walter Piston, William Schuman, and David Diamond, to name only three). Laudable as this devotion has been—and if Schwarz had ignored American music, I’d have been the first to complain—it left little room for exploring other angles of the contemporary scene, so Morlot’s eagerness to bring us recent European music (particularly that of elegant colorist Henri Dutilleux) will be a stimulating change.

The second question is whether the orchestra’s sound and style will change. Under Schwarz, the SSO has leaned toward a richer, weightier sound, built on a firm mass of strings (one reason the orchestra’s performances of 18th-century music, which thrives on transparency, tend to be less invigorating). Conventional wisdom says the French playing style sounds leaner, lighter, tauter, favoring cleaner textures and purer colors—or at least used to, back when the musicians in any given orchestra were more homogenous in background and national differences in approach consequently more pronounced. Is that still true? If so, who is mainly responsible for cultivating that sound—is it the result of the tastes and choices of French conductors, transforming any orchestra they touch; or of the insular, meticulously maintained traditions of French instrumental training, and thus not really graftable onto ensembles outside France? And anyway, will refurbishing the SSO’s sound be one of Morlot’s priorities, or even concerns, come September?

One sure thing is that Benaroya Hall will make an ideal showcase for whatever happens. Among the extra-musical ups (growth of the subscriber base) and downs (backstage friction with musicians and management) of Schwarz’s long tenure, the $120 million hall, which opened in 1998, will remain his most important legacy. Not only did he propagandize and fund-raise inexhaustibly for it, all but willing it out of the ground, he presciently insisted it be designed to serve only as a concert venue, not as a multipurpose performing-arts center compromised to accommodate tours of Riverdance and Miss Saigon. Even Schwarz’s detractors, who’ve been wishing for new blood for the SSO for years, can hardly deny him this achievement— one that will contribute to the symphony’s excellence for decades to come, no matter who’s on the podium.