In the opening scene of Grand Concourse at Seattle Public Theater, the audience meets Shelley as she is timing her prayers with a microwave. The distinct beeping of the buttons is heard as she types in one minute, the amount of time she has allotted to challenge herself to speak. The microwave’s dim yellow backlight shines upon her as she attempts to formulate conversation with her sense of the divine, ultimately struggling for words. “People are fucked up, Shelley,” Frog (played by Cory McDaniel), a regular attendee of the Bronx soup kitchen Shelley runs, later says, calming her guilt for struggling to extend compassion through devotion. With a substantial focus on the drama of boundaries and forgiveness, Grand Concourse simultaneously leaves a parallel narrative around homelessness half-baked.

As time has worn on, this overly generous nun (Faith Bennett Russell) has run out of patience and a capacity for forgiveness, despite support from sassy security guard Oscar (Tyler Trerise). After years of servitude, Shelley is understandably tired—or as they call it in the show, “faith fatigue”: exhaustion from caring for those the state views as disposable.

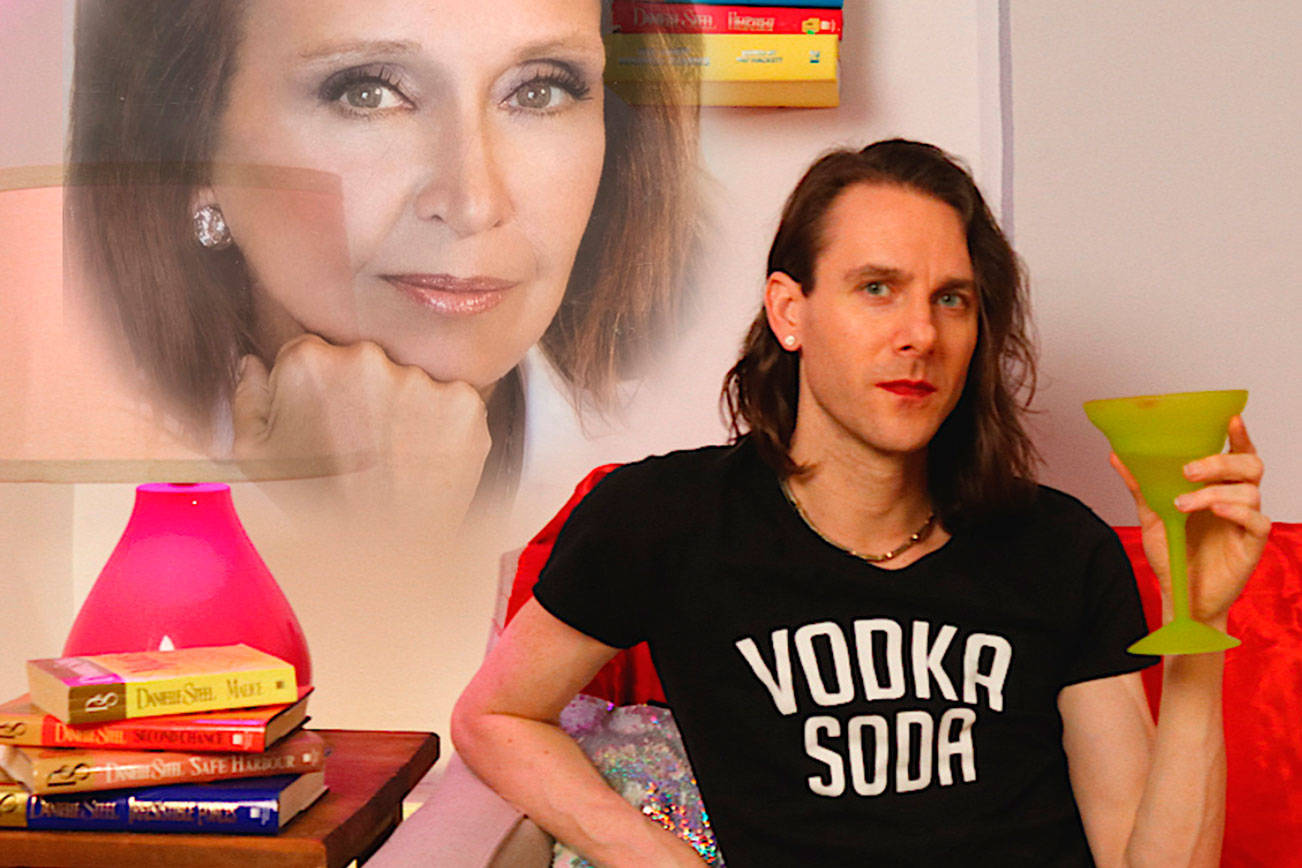

Grand Concourse was written by Washington native Heidi Schreck, perhaps best known as an actress in the TV show Nurse Jackie and as a writer for I Love Dick, a new show on Amazon. Her TV-writing style is evident on the stage, with dramatic plot twists and timely reveals, complemented by the work of Evan Christian Anderson (lighting), Jenny Littlefield (scenery), and Robin Macartney (props). Anderson’s lighting is particularly excellent when characters are standing alone: dramatic pauses at doorways in and out of the industrial kitchen, looking toward the light of the church’s stained-glass windows, or entering the sleepy kitchen at dusk. The mood in the kitchen shifts dramatically when white, self-involved 19-year-old Emma (Hannah Ruwe) enters. “I thought if I gave back in some way, do something for other people, it would help,” she shares with the kitchen crew near the beginning of the play.

Throughout, Shelley and Emma rapidly swing from despair to joy and back again. This switch between very different emotional spaces was disorienting as an audience member. With a heavy focus on caregiving, “faith fatigue,” and Emma’s drama, a nuanced homelessness narrative was lost in the melodrama—unfortunately, given Seattle’s very real struggles with the issue. Frog’s character seems to lean on similarly unfortunate mental-illness stereotypes. Emma’s cheap jokes about “bums” and “crazies” produced laughter in some audience members, unease in others. In that way, Grand Concourse’s vision of homelessness seemed like an afterthought that left me craving a more attentive take on the intersection of homelessness and care.

Grand Concourse, Seattle Public Theater, 7312 W. Green Lake Dr. N, seattlepublictheater.org. $17–$34. All ages. Ends June 11.