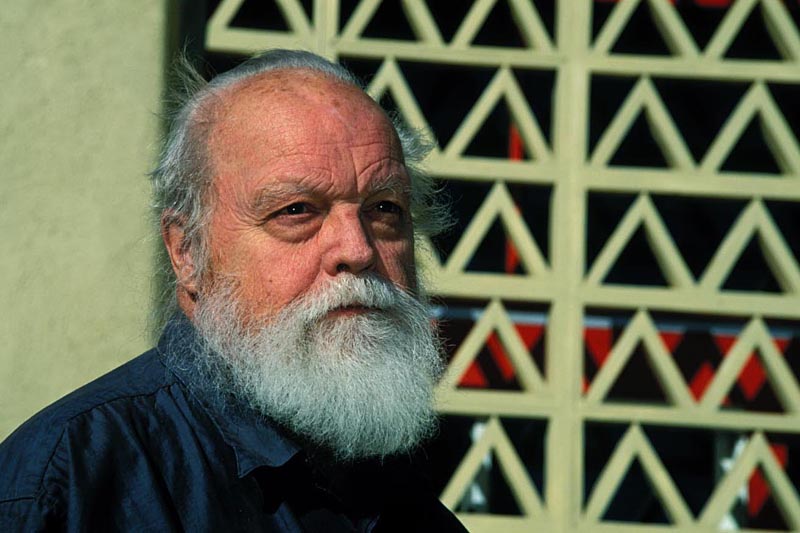

Lou Harrison died in 2003 at a Denny’s in Lafayette, Indiana—a mundane end for a composer who unprecedentedly opened American ears to music from the other side of the Pacific Rim, from Japan to Indonesia. Filmmaker Eva Soltes spent two decades capturing Harrison at work and in interviews, and there’s plenty of him in her just-finished doc Lou Harrison: A World of Music, playing this weekend at the Grand Illusion. Born in Portland in 1917, Harrison enjoyed an upper-middle-class family life until the Depression, which induced his parents to move to California. There, Henry Cowell turned the curious young musician on to non-Western music; John Cage introduced him to percussion; and Arnold Schoenberg, at UCLA, instilled the doctrine of simplicity—a no-frills aesthetic in which every note in a piece tells. For Harrison, this meant melody-oriented, rhythmically infectious music of a serene, elevated exoticism, startling and liberating during those contentious years of aggressive musical modernism. Harrison ended up in New York City during and after WWII, as every artist did; then, after a nervous breakdown and a teaching stint in North Carolina, he landed back in California in 1953, in the laid-back village of Aptos on the coast south of the Bay Area, and at last made just the life he wanted: instrument-building and sound-experimenting with his partner of 33 years, William Colvig. High-profile collaborations with the San Francisco Symphony, California’s new-music-friendly Cabrillo Festival, and choreographer Mark Morris brought to wider attention the fey hippie-Santa persona the composer joyously cultivated. An out-and-proud pioneer, Harrison remarks onscreen here that “I need to leave an opera on an overtly gay theme . . . historically founded, and the real thing.” The result was the star-crossed Young Caesar, conceived first as a puppet opera, then as a choral opera (premiered by the Portland Gay Men’s Chorus), then slated for a full Lincoln Center staging—a plan kiboshed by 9/11. It was the one major disappointment in a career marked by untiring generosity and encouragement to younger composers to stay true to the needs of their own inner ear.

Go East, Young Man

A new doc profiles the composer who made the gamelan safe for America.