Focus

Opens Fri., Feb. 27 at TK theater. Rated R. 104 minutes.

A good con artist movie isn’t that much different from a good con. It’s all about distraction and sleight of hand, creating a false narrative to draw the viewer’s attention away from the real plot playing out behind the feint, and leaving behind a story that the mark can hang on to.

Will Smith is all arrogant confidence as Nicky, the veteran pro who runs his jobs like a coach fielding a champion team in Focus. He’s not interested in one big score, but in racking up points in a rapid-fire succession of plays throughout the game. Margot Robbie (The Wolf of Wall Street) is working class grifter Jess, the minor league talent who proves to be a natural as the distraction if not a star player of Nicky’s squad.

The team picks pockets in New Orleans, rubs elbows with the rich and reckless in a Super Bowl sky box, and hits the race track circuit in Buenos Ares, all while a jukebox soundtrack of bouncy beats sets the tone. That’s part of the fun of the con movie: the rush of grifting as the just desserts of the rich and corrupt meted out by beautiful people and eccentric sidekicks.

Filmmaking team Glenn Ficarra and John Requa, who wrote Bad Santa and directed Crazy Stupid Love, seed the script with clues and suggestions and comic relief (Adrian Martinez as Nicky’s harmlessly crude partner in scam) to keep us looking in the wrong direction, manufacturing one kind of drama while surreptitiously playing out another. It’s kind of fun as those things go, at least until the con is dropped. Without their carefully cultivated pose in place, Smith and Robbie have nothing to fall back on and are left to bicker like idiots. It would be clever if that was the point, but it’s merely a failure of imagination.

Focus would like nothing more than to evoke the easy style and playful personality of the Oceans movies, but surface glamor is no substitute for character. The boyish charm that made Smith a star feels strained here, and his Nicky comes off as just another stock character in his arsenal. Jess is stuck as the sexy ingenue, always a step behind the play, and Robbie is as much audience substitute as diversion. A touch of healthy cynicism from the filmmakers would help, but I’d settle for even a little ambivalence. Ficarra and Requa are so busy keeping us guessing at the endgame with their carefully engineered bluffs and feints and reversals that they fail to give us a story.Sean Axmaker

A Fuller Life

Runs Fri., Feb. 27–Thurs., March 5 at Grand Illusion. Not rated. 80 minutes.

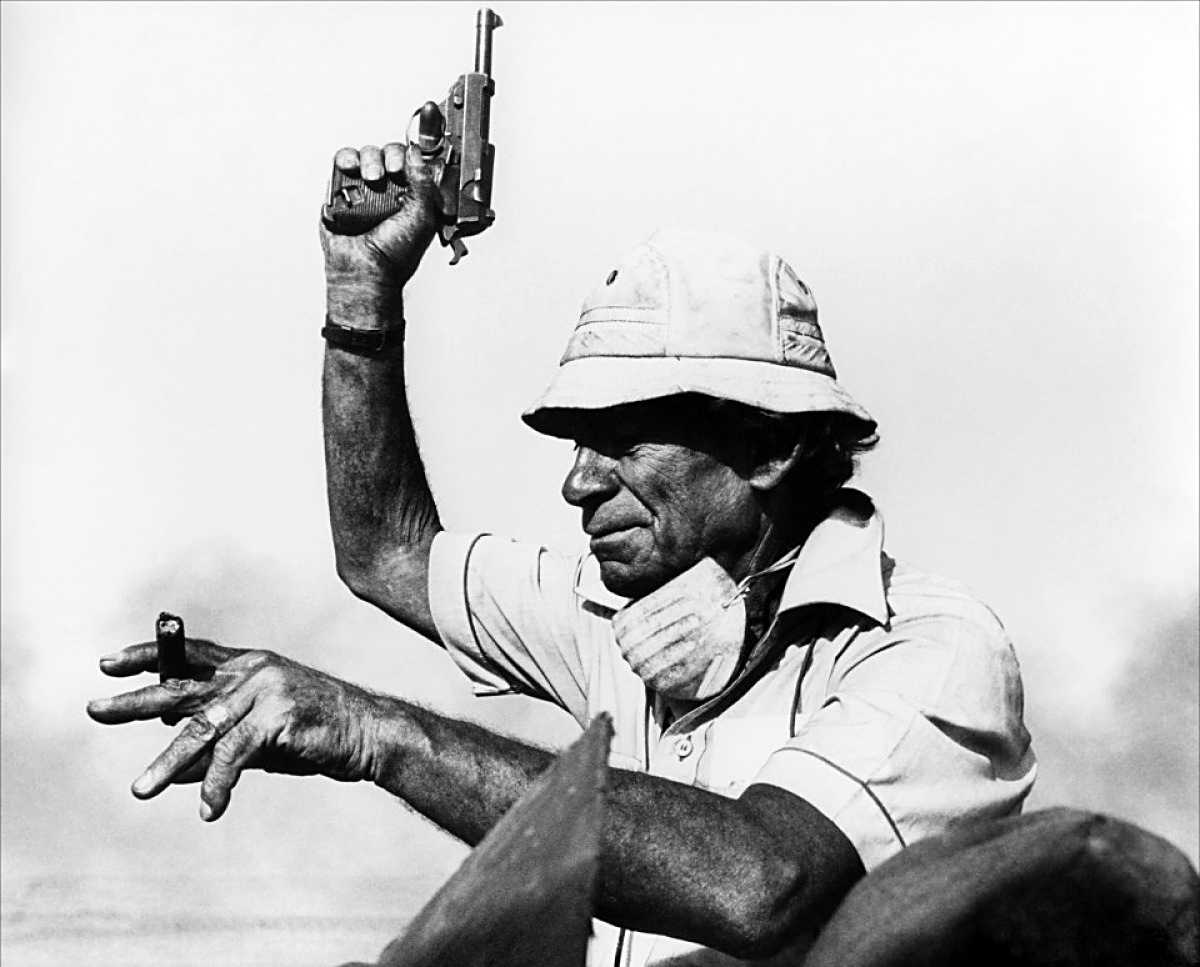

If you are already a fan of Samuel Fuller’s uncompromising pulp cinema, you’ll be delighted by this new documentary tour of the director/writer/producer’s life and career. If you’ve never encountered one of his two-fisted yarns, you’ll almost certainly wonder how you got this far without stumbling across this flabbergasting character. A Fuller Life is ingeniously designed. The screenplay is drawn entirely from Fuller’s posthumously published 2002 memoir, A Third Face, spoken on and off camera by a gallery of intriguing readers: cast members from Fuller’s Big Red One (including Mark Hamill), fellow filmmakers such as Wim Wenders and Buck Henry, and the inescapable James Franco. Fuller’s scandal-sheet-ready prose is accompanied by (very brief) clips from his pictures, plus some fascinating footage he shot as an infantryman during World War II.

Infantry? Yes. Fuller (1912–1997) was already a successful Hollywood writer when he volunteered for the Army’s 1st Infantry Division, a decision that took him to North Africa, the D-Day landings, and the ovens of the Falkenau concentration camp. He signed up as a grunt because he figured that’s where the stories would be, an instinct honed in his scrappy teen years as a hungry reporter for New York newspapers. Fuller’s life is an incredible American saga, a tale of gigantic personality undaunted by poverty or danger. His recollections are hardly black-and-white, however, and his descriptions of postwar nightmares give the lie to notions of glory or heroism.

His films do that, too. They also stir up trouble—critics still can’t figure out whether he’s right-wing or left-wing—a habit that brought scrutiny during the Red Scare when FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover found Pickup on South Street less than patriotic. A Fuller Life is directed by the filmmaker’s daughter, Samantha (of course she’s named Samantha), who crafts it with affection and a keen sense of where the good anecdotes are. It would be great to see more film clips, even from the acting turns Fuller did; a moment from Jean-Luc Godard’s Pierrot le Fou leaves out the scene’s most famous line, in which Fuller defines cinema as though he’s dictating the lead paragraph of a tabloid story: “Film is like a battleground: love, hate, action, death . . . In one word, emotion.” A juicy writer, Sam Fuller was a vivid, often startling director—but for a taste of that, you’ll have to see the excellent 1996 doc The Typewriter, the Rifle & the Movie Camera.

Better still: During the run of A Fuller Life, the Grand Illusion theater will host one-off screenings (in appropriately gritty 16 mm.) of Fuller’s wild Shock Corridor (1963) and equally strange but compassionate The Naked Kiss (1964). Stumble in, and be flabbergasted. Robert Horton

Maps to the Stars

Opens Fri., Feb. 27 at Sundance and TK SIFF Cinema Uptown. Rated R. 111 minutes.

As I write this, the memory is fresh of Julianne Moore winning her Oscar—finally!—for mentally perishing in About Alice. It’s not a great movie, but who cares? She’s done so much excellent work over the years that there’s no point in quibbling over her superior performances in much better films. (And yet I can’t help myself: Boogie Nights, Far From Heaven, The Hours, The End of the Affair . . . but no, back to the movie at hand.)

Maps’ second most prominent name, after Moore, is that of director David Cronenberg, who has also had a long, though more varied, career, including both highs (The Fly, Eastern Promises) and lows (eXistenZ). He began in horror, while Moore started onstage and in soaps. But Maps really bears the imprint of screenwriter Bruce Wagner, whose insider novels about Hollywood (I’m Losing You, Memorial, etc.) are drenched in knowing wit and sordid detail. It doesn’t matter if his Tinseltown writing has any basis in truth; his novels’ appeal—and I am a guilty fan—lies in readers wanting to imagine the worst about their matinee idols. Maps is the product of such venomous, take-down confabulation. It’s beneath Moore, but also a nasty and nearly welcome tonic for her dull, blameless martyrhood to Alzheimer’s in About Alice.

Maps has a different fate in store for the Oscar-hungry, over-the-hill actress Havana (Moore), who hires a particularly unsuitable young woman as her personal assistant (or “chore whore” in the parlance). Agatha (Mia Wasikowska, from Tracks and The Kids Are Alright) arrives without prospects in L.A., her only contact a Twitter friendship with Carrie Fisher (later to cameo, of course). Something’s clearly not right with Agatha, a timid soul on many psych meds and covered with burn scars. We’re also introduced to self-help guru Stafford (John Cusack), his wife (Olivia Williams), and bratty teen actor son (Evan Bird); all these figures will play a role in the fortunes of Havana, Agatha, and the dim, decent limo driver (Robert Pattinson, back from Cronenberg’s Cosmopolis) who ferries them all around.

All Wagner novels feature dense, gothic backstories of corruption and conspiracy. Pathologies are revealed, rehab is reversed, and sexual deviance becomes the new white-bread normal. The problem to Wagner’s oeuvre, and here, is that it all becomes so grindingly obvious. We watch to see the worst in Maps, it’s revealed, and absolutely nothing about it is surprising. (Even the ghosts are predictable.) Also, unforgivable in the inside-Hollywood canon, Wagner can’t craft dialogue or be funny to save his life. Billy Wilder’s tossed-away tissues contain more wit than his glib, pissy writing.

As a result, a lot of talent is wasted here. Moore’s Havana, like every other character, becomes more grating and ridiculous the longer we know her. Cusack, his career more ill-starred, suggests a kind of pathetic, defeated Tony Robbins with Stafford (who wears guyliner and those individually toed running moccasins); the long-form writers at HBO could surely do something better with a showbiz charlatan like this.

Still, let it be said that Maps contains at least one good joke: If you’re going to be bludgeoned to death in Hollywood, at least let it be with your own Oscar. Because any other kind of death just isn’t worth having. BRIAN MILLER

Metalhead

Runs Fri., Feb. 27–Sun., March 1 at SIFF Film Center. Not rated. 101 minutes.

She comes from the land of the ice and snow. We first meet Hera as a 12-year-old on an Icelandic dairy farm. Her beloved older brother wears his Viking tresses long, as any Nordic or metal god should, which proves his undoing. About 10 years later, in the mixtape-cassette early ’90s, Hera (Thora Bjorg Helga) has become the village outcast, tending the cows by day, practicing guitar licks by night. Hera’s parents, more quietly mournful, are baffled. The townsfolk are generally tolerant of Hera’s rages. Everyone expects her to take her dark urges to the big city of Reykjavik, yet she never gets farther than the bus stop.

We can predict that Hera will eventually win over the town and her parents with the power of her music. How Metalhead will get there is more uncertain, this being Icelandic cinema. Writer/director Ragnar Bragason is drawing on his youthful love for Black Sabbath, Iron Maiden, and company, and there’s an intriguing dissonance between Hera’s anger and the widescreen beauty of what we’ve come to think of as the Land of Bjork. The weirdness of most Icelandic movies—or Bjork’s music, for that matter—springs from the eerie desolation of place and the passionate stoicism of its inhabitants. (This is an island where no one ought to live, yet they do.) Hera’s rebellion is more pat; and she, like the movie, has only one song to play.

There’s a sympathetic priest and a doughy suitor, even the late-film arrival of a band that’s heard Hera’s yowling demo tape, but Hera is the only one who can save herself. Yet instead of sending her on some transformative journey, Metalhead is more a Kubler-Ross exercise, which makes its heroine more static than she ought to be. I won’t say this is a disservice to metaldom, but Helga (a former law student) certainly has the talent to plumb deeper scripts that this. By turns scathing, wounded, and contrite, the actress conveys an atonal, akimbo soulfulness that, yes, marks her as a true daughter of the Land of Bjork. BRIAN MILLER

Song of the Sea

Opens Fri., Feb. 27 at Guild 45th. Rated PG. 93 minutes.

It didn’t cop the Oscar on Sunday, but the good news is a few hundred million people have now heard of Song of the Sea. The Best Animated Feature category often includes a title or two that—while utterly obscure by Disney or DreamWorks standards—are at least as impressive in the realm of cartoon art. This year Disney’s lukewarmly received Big Hero 6 was a bit of a surprise winner, its triumph perhaps the result of votes being siphoned off by two tiny but acclaimed competitors, Tale of the Princess Kayuga and this one.

Song of the Sea comes from an Irish company, Cartoon Saloon, whose previous feature The Secret of Kells (2009) also snagged an Oscar nomination. Like that picture, Song is absolutely dazzling in its visual presentation and not so thrilling in its conventional storytelling. The plot is drawn from Celtic folklore, specifically the tradition of the selkie, those mythological shapeshifters who can live on land or sea, as humans or seals. Our hero is Ben (voiced by David Rawle), a young lad whose mother vanishes under dramatic circumstances the night his mute younger sister Saoirse is born. They live on a wee shard of an island with their mournful father (Brendan Gleeson), a red-bearded lighthouse-keeper, but a series of marvelous events lead Ben into a secret world of magical creatures and spell-spinning songs. Little Saoirse, Ben’s nemesis, tags along for the adventure, and in fact proves central to the unraveling of the mystery. (If you’ve ever wondered how to pronounce Saoirse, the matter is settled after hearing it spoken approximately 126 times here.)

Director Tomm Moore lets the movie’s forward momentum run aground at various moments, but he and the Cartoon Saloon crew seem more interested in creating the gorgeous vistas that occupy virtually every frame. The character designs follow circular, looping patterns, and the visual influences seem inspired by anime and the line drawings of 1950s-era UPA cartoons (Mr. Magoo is not forgotten, people). Add the Irish taste for sadness and fairy folk, and the film really does have a distinctive look. It’s even more geared for children than The Secret of Kells, a film I admired but never really felt enchanted by. I can’t shake the idea that the filmmakers really want kids to know about folk tales, as though dutifully passing on a somewhat cobwebbed tradition—when what a tale like this really needs is a storyteller drunk on the dark magic of seals and mermaids and the deep blue sea. Robert Horton E

film@seattleweekly.com