“Do I have to use musicians?” was Trimpin’s first question when planning began for his new commission for the Seattle Symphony. It shouldn’t have come as a surprise, since the German-born local sound artist is best known for working in visual media. His elaborately fanciful and beautiful sound-generating sculptures and installations have graced venues around the world. Closest to home is the giant guitar tree, titled IF VI WAS IX, permanently displayed at the Experience Music Project; and last year his You Are Hear group of listening stations was a summer installation at the Olympic Sculpture Park.

But his original concept—a solo work for SSO music director Ludovic Morlot—remained at the center of Above, Below, and In Between, to be premiered at this Friday’s concert in the orchestra’s [untitled] new-music series. Morlot will control the musical instruments set up by Trimpin in the Benaroya Hall lobby via a motion-capture camera (something very roughly akin to a Wii video-game controller) devised by Dimitri Diakopoulos of Intel. It’s a short step for a conductor who, of course, is accustomed to guiding live musicians by gesture; here, Morlot’s baton-wielding arms, as caught on video, will start, stop, and change the volume of Trimpin’s gadgetry.

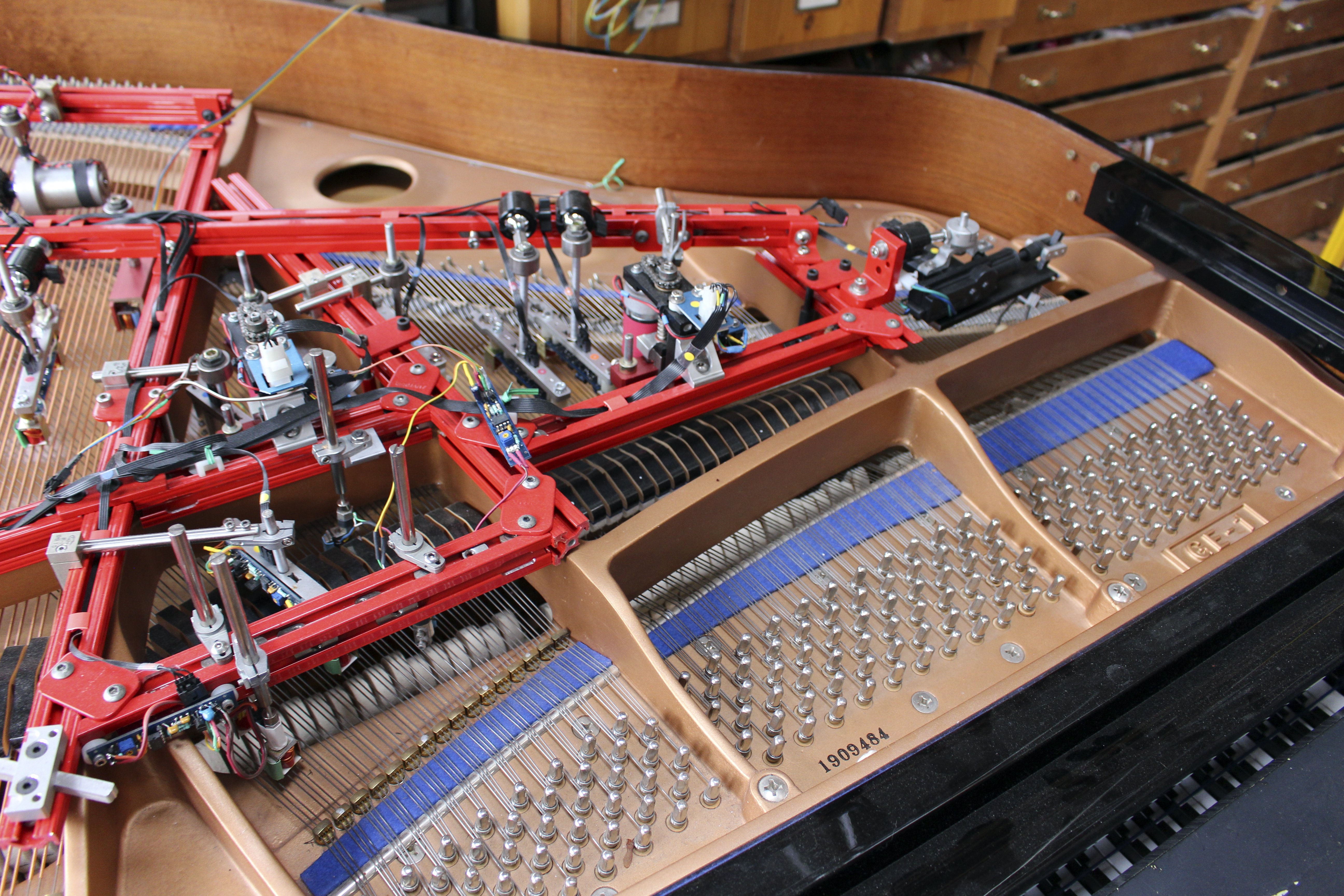

A February visit to Trimpin’s wondrously cluttered Central District workshop—part warehouse, part circus prop room, part Santa’s toy shop—revealed the sound makers that will fill the Benaroya lobby. First are 24 “reed horns”: blue, triangular, organ-pipe-like devices each fitted with a reed and its own blower. An octave and a half’s worth of “Brant chimes,” tubular bells once owned by composer Henry Brant, are each struck by a tiny mechanical piston that taps it delicately. More pistons are set up to strike the keys of a prepared grand piano; also, the piano’s strings will be set in motion by a magnetic field, without anything touching them at all, generating a ghostly, sonorous drone. All these will be placed and hung among the lobby’s nine columns, hence the work’s title. Responding to Morlot’s movements, those blowers and pistons will fill the space with a curtain of delicate and whimsical pings and hums.

As for live musicians, there’ll be 10: two violas, two cellos, two basses, and three trombones spaced out on the promenade level above those nine columns, plus soprano Jessika Kenney, performing Trimpin’s written-out score. (The reason for using strings and trombones is the ease with which they can slide between the notes of the standard scale—unlike, say, pianos—enabling the use of the full spectrum of pitch.)

“Seattle is not aware of what kind of genius we have in town,” says Morlot of his collaborator—particularly ironic since Trimpin is in many ways continuing the legacy of John Cage, whose two years at Cornish College (1939–41) inspired some of his most far-reaching innovations and who became one of the school’s most famous sons. For all their Rube Goldbergian intricacy and technological innovation, the actual sound-making objects in Trimpin’s installations—a struck chime, a vibrating reed, a marimbalike array of wooden bars—are familiar, even comfortingly so, their sounds gentle, inviting, beguiling.

Setting up a complex system, then getting out of its way and delighting in the aural result: This is the joint method of both creators, even though Trimpin employs cutting-edge video technology or earthquake data (vide his “seismofon” at the Science Museum of Minnesota) where Cage used the I Ching and an orchestra of radios. Both men share a playfully enthusiastic yet disciplined demeanor; both fit somehow into a very American tradition of the DIY tinkerer, the “mad inventor.”

Cage, though, found it nearly impossible—to the extent he ever bothered to try—to get access to mainstream performing institutions. (Look up what happened in 1964 when Leonard Bernstein tried to get the New York Philharmonic to play his Atlas eclipticalis.) Yet here’s the Seattle Symphony happily reaching out to and spotlighting his aesthetic descendant—a mere half-century later! Friday’s performance will be yet another example of how the SSO under Morlot is moving, season by season, closer to where it belongs—at the forefront of creativity and novelty in the city’s classical sphere.

gborchert@seattleweekly.com

SEATTLE SYMPHONY Benaroya Hall, Third Ave. & Union St., 215-4747, seattlesymphony.org. $20. 10 p.m. Fri., May 1.