As anyone who watches Antiques Roadshow can tell you, age makes a big difference. A table lamp that was the latest thing for your grandparents might have felt vaguely dated to your parents, while it’s a cherished collectible on your credenza. Likewise, a dance that was on the cutting edge not so long ago can today seem more an example of a past experiment, a step on the way to how things look now.

Serious Pleasures, the fourth work by Ulysses Dove to enter the PNB repertory, feels like one of those in-between dances. Made for American Ballet Theater in the early ’90s, it has an in-your-face sexuality that likely would have been challenging at that time and for that company, but that today seems no more radical than a well-made music video.

The work opens on a man hanging from a pair of bars on a long black wall, tied up in a knot, but then unfolding like a mantis. His swaying and pulsing is echoed in the line of men and women who enter the space after him, though a series of doors in the wall that might be a peep show, a brothel, or just an apartment building. These people may be his community, total strangers, or figures from his imagination. Whatever the interpretation, they work through a series of encounters that are indeed serious, and might be pleasurable, but seem to lack tenderness or joy. When the narrator returns to his perch at the end of the work, we’ve seen a great deal, but nothing much has changed. And in a culture already full of hypersexualized images, a stage full of sensual bodies isn’t really enough.

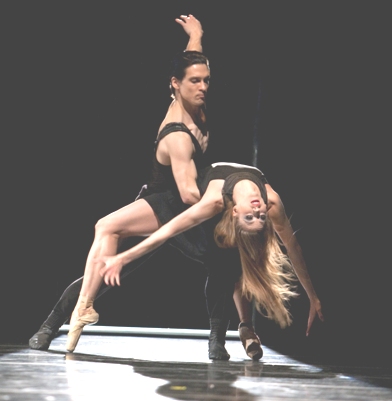

After Serious Pleasures, Dove went on to make Red Angels at New York City Ballet, with a cast that included a young Peter Boal, now PNB artistic director. Red Angels has some of the same characteristics as the earlier work: a celebration of the body as a sensual object, an almost confrontational relationship with the audience, a fascination with the possibilities of balletic virtuosity. But in this work, Dove plays with the relationships between the dancers and with our expectations of the performance. Deadpan isolations alternate with full-throttle zipping through the space, and the two couples flip between eyebrow-lifted disdain and pretzel-y partnering one step away from the Kama Sutra. In a preshow lecture, PNB education program manager Doug Fullington compared the self-possessed strut in the ballet to a model working the runway, and it does seem to have that catwalk feel.

Only a year separates these two ballets, but looking at them today, they feel as if they represent two very different times and places. The edgy heat of Red Angels many have come from the more implacable sensuality of Serious Pleasures, but right now Angels continues to feel like a contemporary work, while its predecessor remains in the past.

The two other works on the program, Vespers and Suspension of Disbelief, ask the dancers to use skills outside their usual background. Vespers, also by Dove, is rooted in modern-dance techniques, and works best when it’s performed by people for whom that grounded power is second nature. Victor Quijada, who made Suspension for PNB in 2006, originally comes from a break-dance background, and his dance is full of those isolations, off-vertical balances, and spine-twisting shapes. In both these works, it’s amazing how close the PNB dancers get to the heart of the varied styles, but their skills make us wonder what those dances would be like with performers who put that material first.