Time and again, Pacific Northwest Ballet’s artistic director Peter Boal has said he wants audiences to see the variety of dance his company can accomplish—more than just ballet. So it’s ironic that one of the most exciting works in the company’s current “Director’s Choice” program is based firmly in the 19th-century classical tradition. Val Caniparoli’s The Seasons is a new ballet with some very old roots.

Several Caniparoli works are already in the PNB repertory, ranging from the contemporary abstraction of Torque to the wartime tension of The Bridge, but probably his best known dance is Lambarena, to a score that combines J.S. Bach with African drumming. The Seasons is like none of those. Here, Caniparoli reaches back to an 1899 score by Alexander Glazunov, originally written for Marius Petipa—the architect of classical ballet style. Of course, modern choreographers scavenge from the past all the time, but in this case Caniparoli has adopted Petipa’s original scenario as well—a mildly silly thing full of nymphs and satyrs—as well as the traditional structure of a classical work, with its full hierarchy of corps, soloists, and principals.

Rather than borrowing steps from other dance traditions, Caniparoli is digging into his own, crafting some impressive sequences, flashing and skimming across the space, and pulling out an unexpected series of historic quotations from iconic Russian works like The Firebird and Afternoon of a Faun. The Seasons is not a perfect ballet; it drags in a couple of places, and some of the transitions could be clearer. But it is a heartening and fascinating attempt at developing a traditional art form. Instead of seeing what else ballet dancers can do, Caniparoli is looking at what ballet itself is capable of.

The other big premiere in this program is an impressive acquisition. Jiri Kylian, who directs the Nederlands Dans Theater, has been a leader in combining ballet and modern dance, and her 1991 Petit Mort is a benchmark example, a sleek and sexy piece that plays sleight-of-eye tricks on its audience. There are references to the 18th century of the Mozart score, with corsets, rapiers, and ball gowns, but the movement is from our own time. In partnering, the six couples in the cast are often interlaced in complicated knots, weaving and untying themselves. The heart of the work is a series of duets for the six couples in which they take apart classical posture and deportment; knees turn in as often as they turn out; and love is expressed with the tip of a sword.

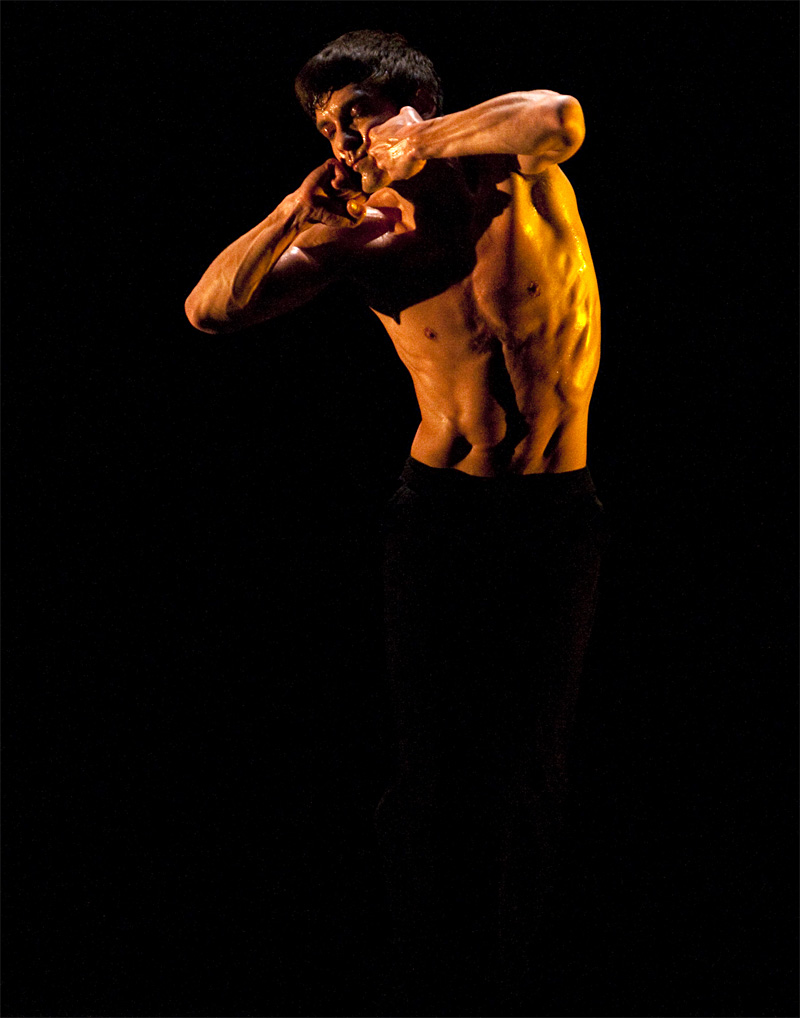

The rest of the program—West Side Story Suite (Jerome Robbins’ 1995 reduction of his Broadway musical), and Marco Goecke’s Mopey (2004)—is already familiar to Seattle audiences. The latter is a tour de force of sulky teenage angst, a juicy challenge for its solo male. Both James Moore and Benjamin Griffiths made the most of this opportunity to emote, especially Griffiths, who transformed his usually sunny persona into a harsher character.