Compare-and-contrast shows are generally a gimmick, pairing artists by virtue of school, medium, nationality, or generational proximity. But sometimes they work quite nicely, as is the case with Isamu Noguchi and Qi Baishi: Beijing 1930, the first of two twinned exhibits at the Frye. (More below on the second, local, and much smaller companion display.) This pairing is a traveling show from the University of Michigan Museum of Art, and it boasts the biggest name: the Japanese-American artist Noguchi (1904–1988), working in an atypical idiom during a very brief, concentrated period.

His story goes like this: Noguchi was in 1930 a rising young New York sculptor, uneasily assimilated into a culture that was casually racist toward Japanese though not yet so vehemently as during the war years. Paris, where he’d previously studied under Brancusi, was still feeling the shakeout of abstraction—not then Noguchi’s metier. Arriving in China, not speaking the language, must’ve been a culture shock. Native art was strictly realistic, historical, and mythic. Visiting a friend in Beijing, Noguchi expressed an admiration for Qi’s scroll paintings; the two artists were introduced—Qi being 40 years older—and met several times over six months.

Theirs was a relationship born of materials shortage: Noguchi couldn’t find the right plaster for sculpture (only one is on display here), so he took up the traditional Chinese calligraphy brush, Qi’s preferred instrument. It was like a crash course in painting for the L.A.-born artist, and he never again returned to that idiom.

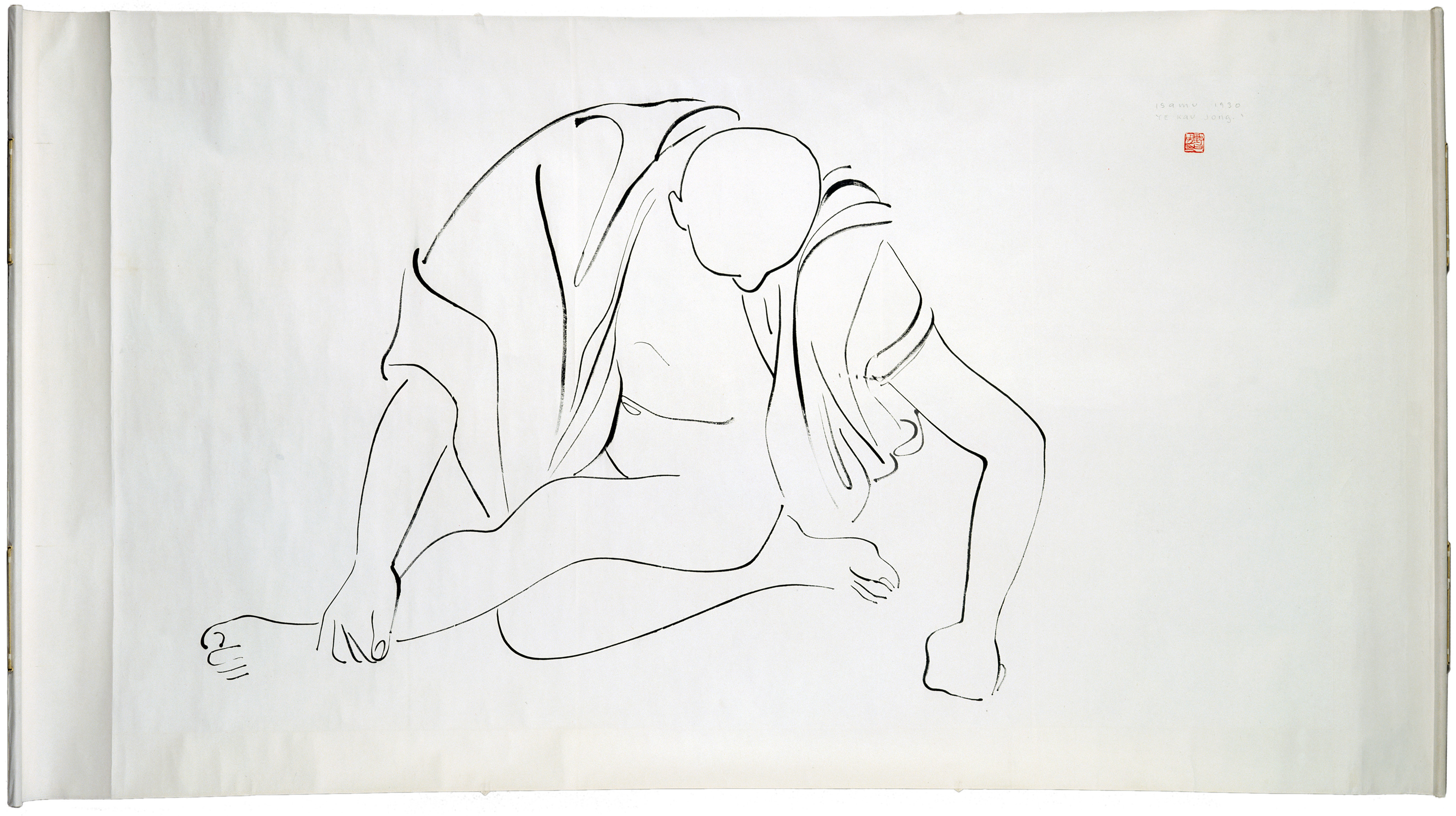

In 31 works by Noguchi and 25 by Qi on display here, the contrasts are fairly obvious: Qi depicts landscapes, animals, still lifes, and mythic figures, often employing color; Noguchi works from live figure models—unheard of then in China—and renders them in sparse, gestural brushstrokes of black on white (lots of white). You get the historical details in Qi, the human outlines in Noguchi. Everything in Qi is pictorial and backward-looking; these small, delicate paintings would hang handsomely on your walls, even if you’ve seen thousands more just like them. Noguchi’s nude women and babies are larger and looser, sometimes rendered horizontally on the parchment. There’s no background, no context but white; they could’ve been painted this morning, for all we know. They’re modern, in simple terms, with hints at the future abstraction that would characterize Noguchi’s mature sculpture, landscape design, and furniture of the postwar period. (His most famous local work, 1969’s Black Sun, stands outside the Seattle Asian Art Museum.)

Everything about this anomalous interlude in Noguchi’s career is easy on the eye, ready for tea mugs and tote bags. After his famous coffee table was mass-produced by Herman Miller in 1944, he became a saleable international brand. His nudes and wrestlers here are all elbows and knees, often crouched toward or slumping on the floor. Their poses are almost like furniture; the body is warm and palpable but almost structural. We see Noguchi proceeding inevitably to his future, sparser design vocabulary.

The second, smaller adjunct show organized by the Frye is Mark Tobey and Teng Baiye: Seattle/Shanghai. Venerated in the Northwest, where he lived intermittently from the early ’20s to the early ’60s, Tobey left such a long, contentious legacy here that he really deserves his own major retrospective. What we get instead are a baker’s dozen of his excellent canvases, several from the “white writing” postwar period supposedly inspired by his 1934 reunion with Teng, a younger University of Washington student he met in Seattle during the ’20s.

Tobey (1890–1976) learned some calligraphy in the ’20s from Teng, most of whose work was later destroyed during the Cultural Revolution (little is displayed here). And Tobey, the spiritual polyglot and seeker, certainly absorbed many currents from Asia. He was a syncretist, borrowing and appropriating what he liked, describing it how he pleased. Recalling his 1934 visit to Shanghai, he’s quoted as praising the “twisting and turning” of Chinese calligraphy. In 1957, he told The Seattle Times, “The Orient has been the greatest influence on my life.” Maybe that’s true, maybe it’s hyperbole. Does that influence directly manifest itself in the work he began producing in the mid-’30s?

If you look at the vibrating, lacy rectangular mass of an untitled 1954 work seen here, Tobey’s intricate ivory interweaving resembles a block of coral. The fine brushstrokes and distinct lines could almost be writing or calligraphy if you could somehow pluck out a component piece; but it’s more like the phraseology of a made-up language, the synapses in a neural network. The density and energy jump off the picture surface, and you can understand why Jackson Pollock was an early admirer of Tobey’s work. (We’ll see more of the latter in SAM’s big Northwest modernism show in June.)

Still, Tobey isn’t actually writing or using calligraphy, as Qi and Teng employ in their traditionalist scrolls. Tobey didn’t read Mandarin; it’s the shapes, not the sense, of the characters that he and other Western artists found so appealing. This is when “the Orient”—now an outdated, even suspect term—was exciting and new to the bohemian circles of Tobey and Noguchi. Eight decades ago, to be called an “Orientalist” was something of a smear. Now it seems like more of a vindication.

bmiller@seattleweekly.com

FRYE ART MUSEUM 704 Terry Ave., 622-9250, fryemuseum.org. Free. 11 a.m.–5 p.m. Tues.–Sun., 11 a.m.–7 p.m. Thurs. Ends May 25.