As you enter the theater for Bridges International Repertory Theatre’s inaugural production, you see an Oscar Wilde quote projected onto the wall: “A map of the world that does not include Utopia is not worth even glancing at, for it leaves out the one country at which Humanity is always landing. And when it lands there, it looks out, and, seeing a better country, sets sail.”

A MAP OF THE WORLD

Bridges International Repertory Theater ends February 4

In the context of David Hare’s play A Map of the World, set around a world poverty conference, such a quote could underscore the cynical view that even when humans discover perfection, they still find infinite ways to screw it up. Throughout the play, speeches chock-full of good intentions are convincingly shot down by the next speaker as the product of greed, arrogance, or self-delusion.

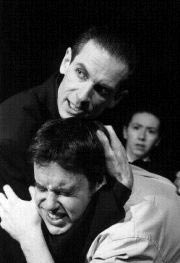

At the center of these ongoing, engaging arguments are the young Englishman Stephen Andrews (Jason Cottle), a literary, left-wing magazine writer, and Victor Mehta (Siddhartha Chakravarti), a much-admired expatriate Indian novelist who has been invited as the conference’s keynote speaker. The sparring between Cottle and Chakravarti is exquisite, as every passionate ideal brought up by Cottle’s deferential rage is succinctly deflated by Mehta in a gentle torrent of witty abuse.

Mehta happily derides every idea surrounding the conference. An eloquent plea by a Senegalese diplomat (Kevin Warren) asking that Mehta downplay his disparaging views of communist countries is met with a refusal to abandon the truth. Even the nudges of the beautiful Peggy Whitton (Rachel Glass), a promiscuous actress from the New York suburbs (a thankless role full of references to innocent youth), hardly sway the caustic novelist. Although it forces him into isolation, Mehta is determined to hold onto his beliefs—because he is right, because he knows that the methods of the conference detract from any utopian ideal.

Yet maybe the point of the play isn’t utopia or being right; the point is being human. Seen in this light, it doesn’t matter that the poverty conference isn’t a well-oiled machine that reaches down with a flick of its benevolent wrist to rescue the unwashed masses. Instead, the conference exists to fulfill the need of humans to help one another. Hare exposes the larger inhumanity of the relationship between the Third World and the West, which doesn’t include the economic fact of aid—though this is abysmal enough—but the way in which the aid is given that robs the poor of their dignity. Mehta’s initial refusal to invest himself in the world ignores the notion that it is the hope of changing the world that defines our humanity.

“This feeling, finally, that we may change things, this is at the center of everything we are,” Mehta says at the end of the play. “Lose that, lose everything.”

This push toward change is also the greater point of Bridges. In the post-play discussion, which will follow every performance, the audience was asked if their views had shifted. One man reflected, “I know even less than I thought I knew. I can’t possibly put my life into one that’s so different from mine. I can try, but I don’t think I’ll get there.”

Yet, in a sense, it is more important that the man try to identify with someone different because that is the first step to getting there. Bridges asks us to open ourselves up to the possibility of change without offering any direct answers of what that change should be. And whether you buy that will determine which side of the bridge you stand on.